They rake through their memories for signs.

Could her family have seen more? Done more? Yes, Latarsha Sanders was off-kilter, even bizarre at times, but she had never hurt her kids. As paranoid and obsessive as she could be, nothing hinted at the horrors to come. And if they’d tried to get her help — unlikely, given the family’s wariness of therapists — Sanders would have refused to accept it. She had been prescribed trazodone, a medication used to treat major depressive disorder. Sometime in 2017, she told her daughter Shalea that her doctor had given her “mood pills” but she wasn’t taking them.

“She would never accept help because if she did, she would have to admit she had a problem,” said her brother, Harvey Sanders.

Sanders’ attorney Robert F. Shaw Jr. declined to make her available for an interview, citing severe psychiatric issues.

As a child, Sanders could be distant and prone to emotional extremes. She had few friends, her mother recalled.

“Coming up, Latarsha was strange,” she said. “She would go to school and start arguments for no reason. And when she did get a friend, it would be ‘This is my best friend,’ and I thought, How? You just met her.”

Sanders’ mother asked that her name be withheld, because she is trying to rebuild her life and feels judged for what her daughter did. She raised Latarsha and her younger brother, Harvey, mostly alone. Life at home was turbulent for the siblings before their parents parted, when Latarsha was around 9.

“My grandmother didn’t believe in psychiatry so no one was getting help,” said Harvey Sanders. “Coming up, we learned, ‘Hey, keep our business in the house, [because] you might get taken from your parents.’ ”

Still, when Sanders was 8, her mother was so worried that she brought her to see a therapist. The girl refused to speak during the appointment. That was that.

“It took a lot for me just to take her there,” her mother said. “So I [was] not going back.”

Sanders began running away from home when she was 12 or 13, her brother said. Around her 15th birthday, she became pregnant with her daughter Shalea and was done with school. After that, she relied on public assistance.

“As she got older and things weren’t going right, she had so much weight on her shoulders,” Harvey Sanders said. “She was always on welfare, always having trouble getting by.”

Still, Sanders was a great mother, her eldest daughter said. She loved to cook, going all out for holidays with extended family. She kept on top of doctors’ appointments and grades. She “did not play” when Shalea rebelled as a teenager, sometimes appearing at her boyfriend’s house to demand she come home.

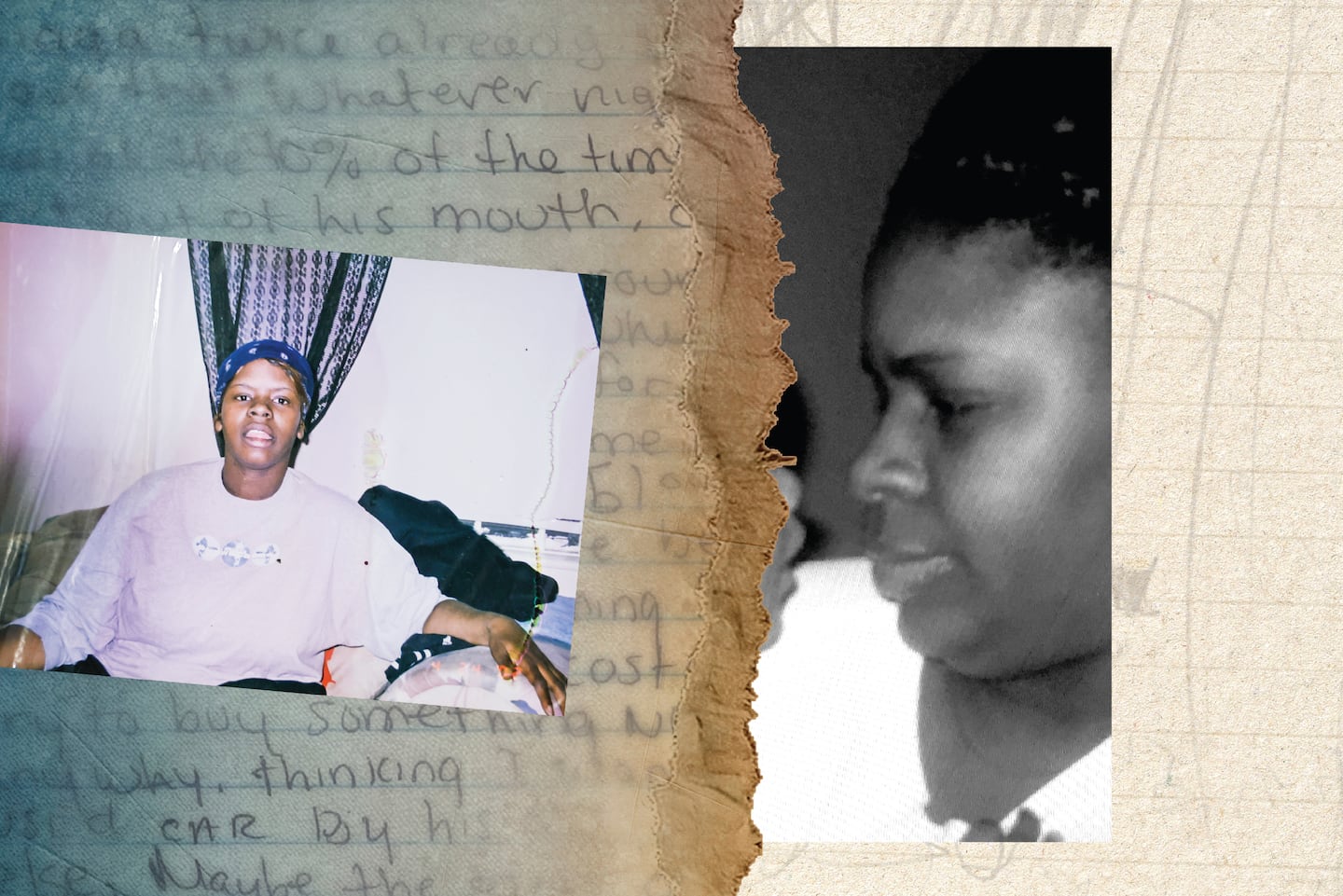

Shalea Sanders at her home in Brockton.Erin Clark/Globe Staff

A handwritten note from Latarsha Sanders to her daughter Shalea. Erin Clark/Globe Staff

“I hear stories about other people and the stuff they went through,” said Shalea, now 35. “My mother would never put me in those situations.”

Latarsha Sanders kept showing up for Shalea after she became a mother herself, right beside her in the delivery room when Shalea gave birth to each of her two daughters. Together, they took their kids to see the fireworks on the Fourth of July and to feed the ducks at D.W. Field Park in Brockton.

To Shalea, the mother who raised her bore no resemblance to the monster prosecutors conjured in the courtroom. “If she was the person they made her seem to be, I wouldn’t have supported her,” Shalea said. “She was wonderful, I wouldn’t trade her for the world.”

Latarsha Sanders met Ixer Alfred and had her son Kadeem with him in 1999. After that relationship, she fell in love with Edson Brito, and they married in 2005. They had a daughter in 2002 (Her family asked that this daughter not be named in this story). They had a son in 2009, and named him Edson, after his father, but everybody called him Marlon. Their youngest child, La’son, was born in 2012.

Sanders doted on her two little boys. As youngest children often do, they got away with all kinds of mischief that would have gotten Shalea in big trouble.

“I would go over there and there would be crayon on the wall,” she said, chuckling. “If that was me at that age, writing on the walls?”

Shalea was closest to Marlon, and he was devoted to her.

“He loved girl stuff, ever since he was a baby,” she recalled. “I don’t know if he was going to be [part of] the LGBTQ community.”

Sanders (center) with family in an undated photo. Erin Clark/Globe Staff

The family embraced and indulged Marlon’s Barbie obsession. They tied extensions into his hair. He loved wearing Shalea’s shoes so much, she bought him his own pair of little heels for Christmas. A year after his death, the students and teachers at the Louis F. Angelo Elementary School, where he was a second-grader, wore pink to honor him.

Marlon also battled gastrointestinal issues that left him unable to tolerate much solid food, and he was often sick. It seemed like Sanders was constantly taking him to see the doctor.

La’son, the baby of the family, always got his way, Shalea said. He was a sharp dresser, and could do no wrong in his mother’s eyes.

“She would let him do whatever he wanted,” Shalea said. “He went to Head Start and he came back and told my mom, ‘They didn’t give me any juice, and the other kids might hit me.’ She never sent him back.”

Sanders was devoted to Brito, and still is, her family said. He did stints in jail, but whenever he was around, he was an involved and loving father.

“She worshiped the ground he walked on,” her mother said. “Her whole world was around him.”

But several times, police were called to their home, arresting Brito for domestic abuse, bringing charges that were later dismissed. Police alerted the Department of Children and Families, but the state did not remove the children, evidently deciding they were safe and well cared-for. A spokeswoman for DCF declined to comment on the case, citing privacy requirements. Harvey Sanders wonders if things might have been different if DCF had taken the boys. Maybe then, his sister might have been willing to get help.

Sanders’ mother said Latarsha worried that someone would steal Brito away. “It was always, the neighbors want the husband, or I wanted the husband,” her mother recalled. Sanders was paranoid about her neighbors, believing they were listening to her through the walls. She accused her mother of stealing DVDs and other things from her.

Edson Brito embraced a family member following a vigil in memory of his two sons in Brockton on Feb. 8, 2018. Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff/The Boston Globe

Edson Brito embraced a family member following a vigil in memory of his two sons in Brockton on Feb. 8, 2018. Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff/The Boston Globe

Sometimes, her mother said, “You’d be sitting here and she would stare straight through you. I would say, ‘Stop staring at me like that,’ and she would get right up in my face.”

In the years before she killed her sons, Sanders stopped taking care of herself consistently, her family said. Some days, she didn’t shower or get dressed. She let her apartment fill with all kinds of junk she refused to part with. Sanders’ mother recalls her oldest son Kadeem being afraid to throw away even an empty cereal box in case that made Latarsha angry.

She put trash bags over the windows, and lay in her darkened bedroom staring at her phone, watching YouTube videos on conspiracy theories. She believed in the Illuminati, a supposed secret cabal that rules the world, and she urged her mother to learn about them too. She became fixated on the death of Kenneka Jenkins Martin, a 19-year-old from Chicago who died of hypothermia in a hotel freezer after she got locked in there at a party, and around whose death there were claims of a cover-up.

Sanders would later tell clinicians that she had been abusing Percocet and that she had been hearing voices since 2016.

But she remained devoted to her kids. A big silver handbag Sanders always carried was stuffed full of papers documenting the business of motherhood: Appointment cards and prescriptions and treatment plans, letters from Marlon’s school, and one of his math journals. She carried around 19 ultrasound pictures from when she was pregnant with La’son and a big red heart Marlon had colored.

Ultrasound images from her last pregnancy were among the papers in a purse Sanders always carried.Erin Clark/Globe Staff

“She was a good mother, but she just had strange ways,” her mother said. “I got so used to her, and just dealing with it. That mental illness … you just sweep it under the rug.”

She could never have imagined where her daughter’s illness would lead.

“I would have taken those stabs for them,” she said. “If I had known she was that off the hook, I would have taken them all.”

Her brother recalled trying to convince Sanders that the neighbors weren’t spying on her, or that the police weren’t watching her house, but she could not be persuaded. Still, he never doubted that the boys were safe.

“I loved my nephews,” Harvey Sanders said. “I wouldn’t just put them aside if I believed they were in danger.”

Shalea, who spent the most time with her mother, didn’t see as many signs of illness as her uncle and grandmother did. But there were moments that made her wonder.

Sanders came to believe a young woman who lived with them for a time was poisoning their food, Shalea said. She developed a fascination with license plates, and every time they’d drive together, she would point out the significance of the numbers, which she said matched family members’ birth dates and death dates.

In January 2017, Brito was arrested at a Brockton gas station and charged with selling drugs, leaving Sanders to parent the younger kids alone, her illness accelerating.

A few months later, Sanders showed up at Shalea’s place in a panic. She said somebody was trying to kill Shalea and begged her daughter to leave with her.

“She was crying tears, and I barely ever saw her cry,” Shalea recalled. “She said, ‘They’re gonna get you!’ and I said, ‘Who are you talking about? Did you take something?’”

None of the people who loved Sanders could have imagined what all of this would add up to. Her episodes were sometimes troubling, but they always passed.

And even if her family had appreciated the urgency of the situation, what could they have done for her before it was too late? Anyone who has tried to get help for someone with mental illness — including those with plenty of time, money, and resources — knows how difficult it is to navigate the system, even when someone is willing to accept help. And Sanders was not willing.

By the time she killed Marlon and La’son, her illness had careened far beyond anything her family had ever seen. Afterwards, when she was sitting in an interrogation room at the Brockton Police Department, it would become clear just how far over the edge Sanders had fallen.

Globe columnist Yvonne Abraham can be reached at yvonne.abraham@globe.com.