A recent study published in Microbiology Spectrum has uncovered groundbreaking insights into how certain bacteria can survive in extreme environments by entering ultra-low metabolic states. This research, led by scientists at the University of Florida, has the potential to reshape our understanding of microbial resilience, especially in the context of space exploration and astrobiology.

The Discovery: A Glimpse Into Microbial Resilience

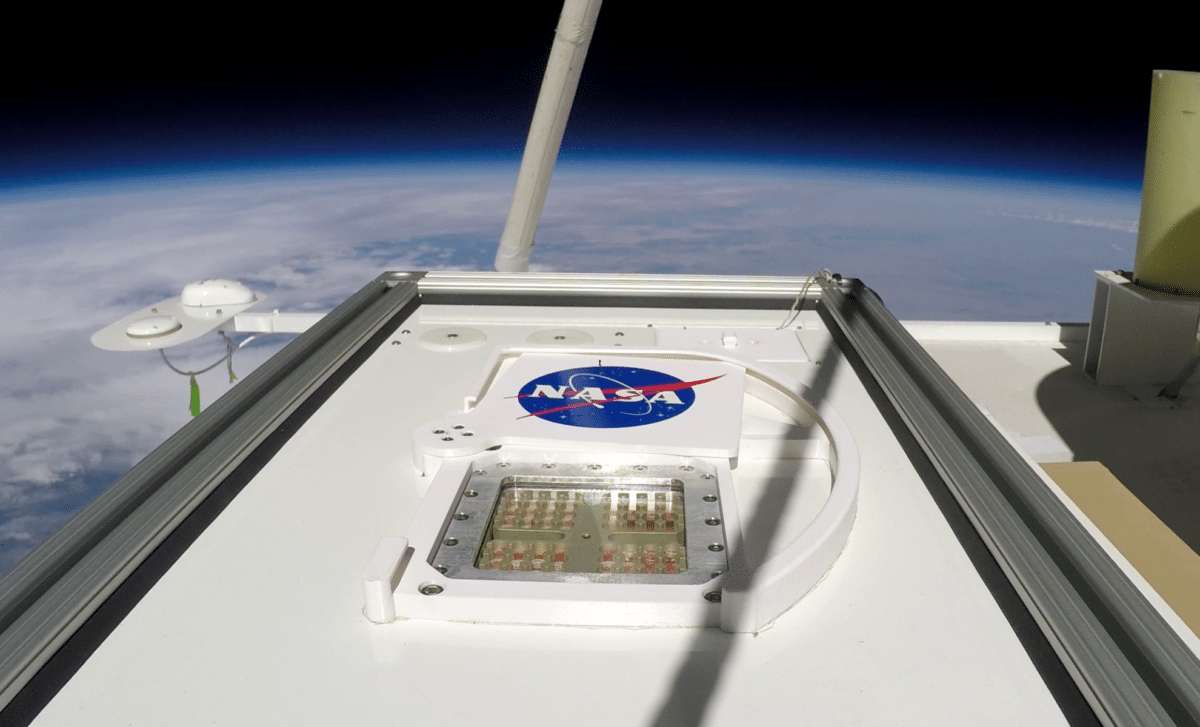

The study published in Microbiology Spectrum explores the remarkable ability of specific bacteria to endure some of the most inhospitable environments known to science. These microbes have the ability to enter ultra-low metabolic states, essentially ‘shutting down’ their metabolic processes to survive harsh conditions, from the vacuum of space to the sterile environments of spacecraft and space stations. Researchers at the University of Florida, led by Dr. Nils Averesch, discovered that these bacteria could maintain their viability despite being in environments that naturally select for only the hardiest organisms.

“It shows that some microbes can enter ultra-low metabolic states that let them survive extremely austere environments, including clean rooms that naturally select for the hardiest organisms,” said Dr. Averesch, who is an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology and Cell Science and a member of the Astraeus Space Institute.

His team’s findings suggest that these bacteria could withstand the conditions found on spacecraft during long-term space missions or even in deep-space conditions, which have always been thought to be too extreme for life.

This discovery has profound implications, not just for microbial survival on Earth, but for the possibility of life on other planets, particularly in environments that are not conducive to conventional survival mechanisms. Scientists now believe that life could persist in more extreme places than previously thought, and that dormant life forms may not need to rely on traditional forms of survival, such as spore formation, to remain viable.

Rewriting the Rules of Microbial Survival

What makes these microbes particularly intriguing is that they do not form spores, a typical survival mechanism for bacteria exposed to extreme conditions like dehydration, heat, or radiation. According to Dr. Averesch,

“What stood out most to me is that these microbes don’t form spores. Seeing a non-spore-former achieve comparable robustness through metabolic shutdown alone suggests there are additional, underappreciated survival mechanisms in bacteria that we haven’t fully characterized.”

This finding challenges the traditional view of bacterial survival, which has long emphasized the formation of spores as the key to enduring extreme conditions. Instead, these microbes rely on a different kind of resilience—suspending their metabolism to survive in harsh environments. By ceasing to metabolize, the bacteria essentially “hibernate,” waiting for more favorable conditions before they reawaken. This unique form of survival could offer an entirely new perspective on how life, including potential microbial life on Mars or elsewhere, could endure long periods of inhospitable conditions.