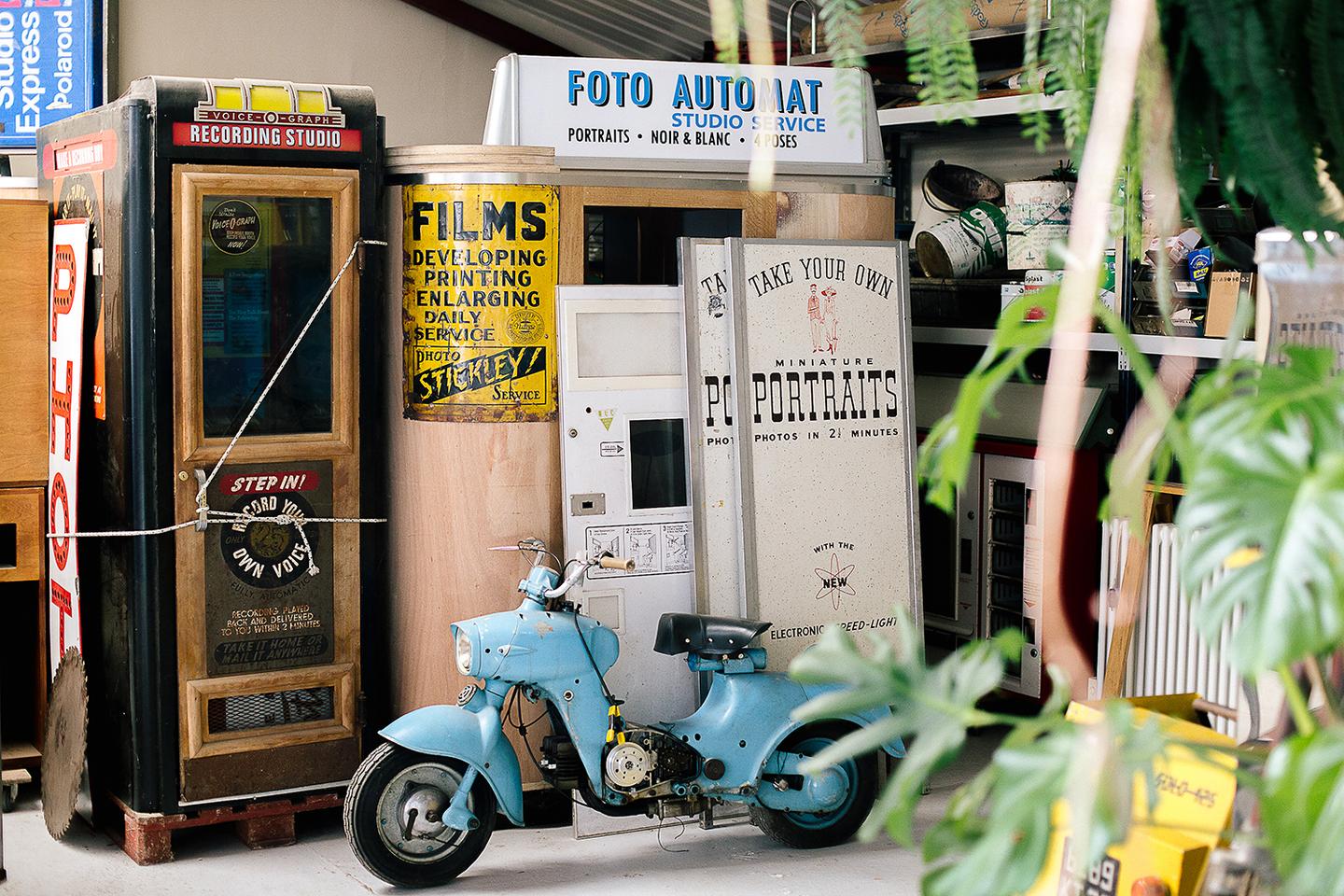

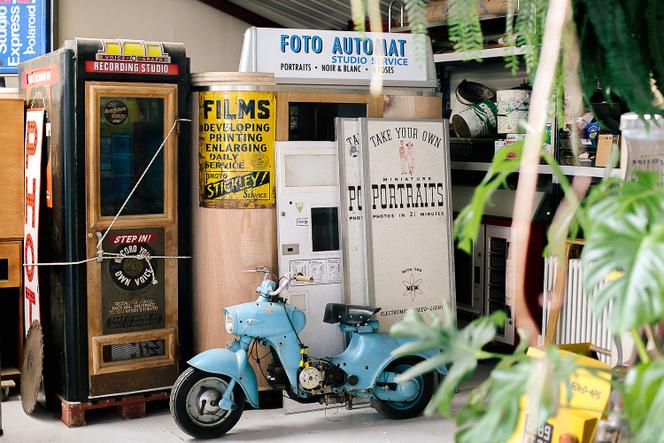

Inside the Fotoautomat atelier in Chartres, October 2025. FLORIAN THÉVENARD FOR M LE MAGAZINE DU MONDE

Inside the Fotoautomat atelier in Chartres, October 2025. FLORIAN THÉVENARD FOR M LE MAGAZINE DU MONDE

Anatol Josepho invented the photobooth one hundred years ago this year in New York. The Siberian photographer’s technical feat meant anyone could step into a booth and, for the equivalent price of “two loaves of bread” at the time, would walk out a few minutes later with four portraits of themselves on film, Taous Dahmani, an art historian and curator of an exhibition celebrating the photobooth’s 100th anniversary at The Photographers’ Gallery in London (“Strike a Pose! 100 Years of the Photobooth,” until February 22, 2026), told Le Monde.

The invention was an immediate hit and soon crossed the Atlantic. Installed in shopping centers and train stations, analog photobooths welcomed both ordinary people and celebrities, such as the Kennedys or John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Artists embraced them – from surrealists to Andy Warhol, and American photographer Richard Avedon, who in 1957 created celebrity portraits using Photomaton machines, later published in Esquire magazine. Over the years, these vintage machines were gradually abandoned in favor of digital versions designed mainly for official documents. Today, only about 200 working analog booths are believed to remain around the world.

In France, a duo has become passionate about this old technology and its vintage appeal. In 2007, Eddy Bourgeois, 46, and Virginie Voisneau, 38, founded Fotoautomat, a company specializing in restoring and preserving analog photobooths. In their Chartres (southwest of Paris) atelier, bathed in October light, some 15 dismantled machines sat ready to be repaired; when one is deemed “irreparable,” its parts may be used to restore another.

An analog photobooth works “a bit like clockwork,” Voisneau told Le Monde. Instead of counting seconds, the photobooth’s parts operate in harmony to produce a strip of film capturing four poses of its subject or subjects. The analog process “does all the work of a studio and a darkroom at the same time.”

A nostalgic Gen Z

Bourgeois trained in Berlin in 2006. A graduate of an art school and passionate about experimental cinema and “anything related to mechanics or motorcycles,” he met Asger Doenst and Ole Kretschmann during a trip to the German capital. Doenst and Kretschmann are behind the revival of these old black-and-white booths in Germany and beyond, with Photoautomat. “Since I was a bit free that winter, I started by lending them a hand,” Bourgeois said.

A year later, Bourgeois installed his first analog booth at the Palais de Tokyo museum in Paris. Today, Fotoautomat has installed seven booths in the French capital, one in Nantes and three more in Prague, often near art or cultural venues such as La Cinémathèque Française or on Rue des Trois-Frères, at the foot of Montmartre and the Sacré-Cœur. Each booth features a unique design created by Bourgeois and Voisneau.

In front of the booth installed by Fotoautomat on Rue des Trois-Frères in Paris, October 24, 2025. FLORIAN THÉVENARD FOR M LE MAGAZINE DU MONDE

In front of the booth installed by Fotoautomat on Rue des Trois-Frères in Paris, October 24, 2025. FLORIAN THÉVENARD FOR M LE MAGAZINE DU MONDE

The booths have gone viral on social media, with TikTok users sharing digitized versions of their film strips. “Gen Z has this thing for nostalgia,” said Hannah, a young photographer from Vancouver who Le Monde met in front of the Fotoautomat on Rue des Trois-Frères. “What attracts people to the magic of the photobooth is not the same today for people as it was in the ’90s or early 2000s,” explained Brian Meacham, the co-creator of photobooth.net, dedicated to archiving and collating the history of analog photobooths, with Tim Garrett. “People want the aesthetic, whatever they think of as that aesthetic, whether it’s the vintage look of the booth itself, or the photos, the way they look in the photos, the whole combination of all those things.”

Read more Subscribers only At Paris Photo, posthumous prints come back to life

Only around a dozen people in Europe know how to maintain and repair these analog booths, and they now face numerous challenges in keeping their passion alive: Film manufacturers no longer produce suitable photo paper. One of the last suppliers, based in Russia, was hit by sanctions after the war in Ukraine.

A photobooth undergoing repair. FLORIAN THÉVENARD FOR M LE MAGAZINE DU MONDE

A photobooth undergoing repair. FLORIAN THÉVENARD FOR M LE MAGAZINE DU MONDE

Despite the difficulties, Bourgeois and Voisneau are determined to continue. “We have customers we met when they were young and single, who sometimes got married, and even proposed in our photobooths. Today, they have children, and they bring them every month to have their photo taken,” so they can watch them grow on that small film strip from their analog booths, which they have helped keep alive for at least 100 years. As Kodak’s founder George Eastman said, “Kodak doesn’t sell film, it sells memories.”

Translation of an original article published in French on lemonde.fr; the publisher may only be liable for the French version.