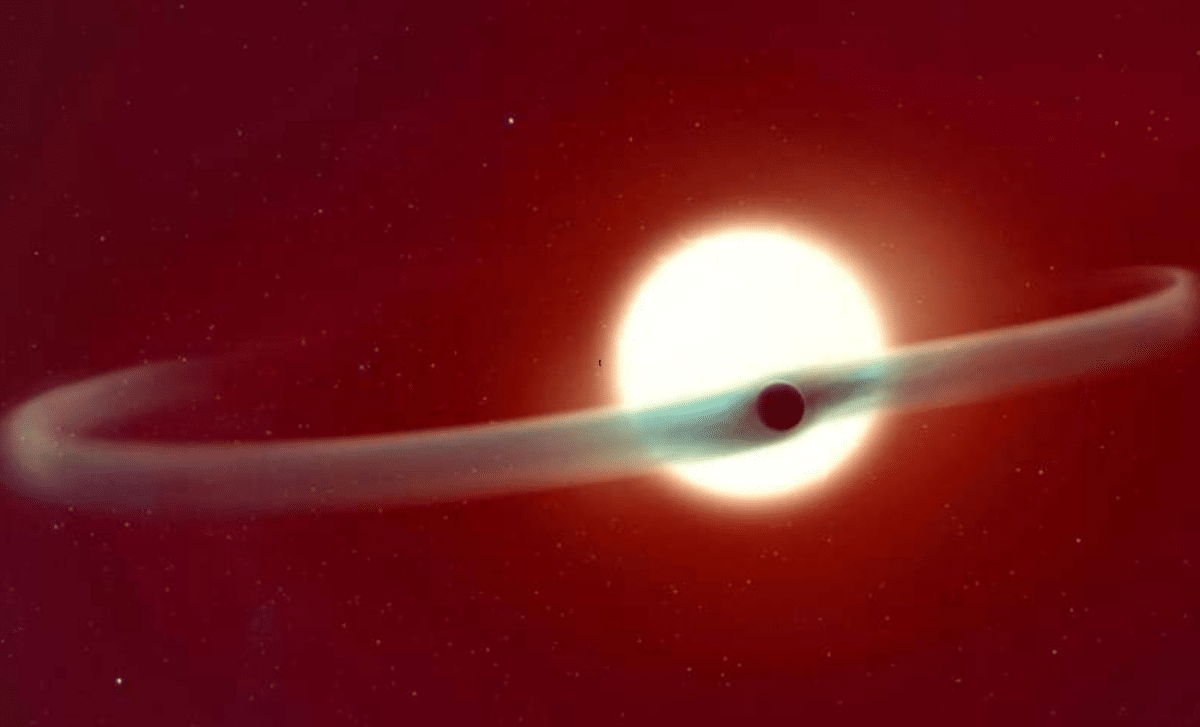

A new study published in Nature Communications has revealed an unprecedented discovery about the exoplanet WASP-121 b, located in a distant star system. Using the powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and its Canadian-built NIRISS instrument, astronomers have unveiled details about the planet’s atmospheric loss, including the discovery of two massive helium tails. This continuous observation of the planet’s atmosphere over a full orbit has provided new insights into how planets evolve under the influence of their stars.

Double Helium Tails: A Stunning Discovery

For the first time, astronomers have captured a full orbit of atmospheric loss around a planet. WASP-121 b, an ultra-hot Jupiter orbiting close to its parent star, was the focus of the study led by Romain Allart and colleagues at the Université de Montréal. Unlike previous observations that only provided brief glimpses during planetary transits, the team used JWST’s NIRISS instrument to continuously monitor the exoplanet’s atmosphere for over 37 hours, covering more than one full orbit. The result? A detailed picture of two enormous helium tails stretching far beyond the planet.

The helium outflows discovered around WASP-121 b are unlike anything previously seen. These two tails—one trailing behind the planet and another leading ahead—extend across more than 100 times the planet’s diameter, with the leading tail likely being shaped by the star’s gravitational pull.

“We were incredibly surprised to see how long the helium outflow lasted,” said Allart, the paper’s lead author. “This discovery reveals the complex physical processes sculpting exoplanet atmospheres and how they interact with their stellar environment. We are only starting to uncover the true complexity of these worlds.”

Reimagining Planetary Evolution

The new data presents challenges for existing models of planetary atmosphere dynamics. Previously, astronomers could only observe atmospheric loss in a limited context—often only during planetary transits. However, the continuous data captured by JWST’s NIRISS reveals much more about how these flows evolve over time. Allart suggests that this discovery could change the way we think about how planets lose their atmospheres.

“This is truly a turning point,” he remarked. “We now have to rethink how we simulate atmospheric mass loss—not just as a simple flow, but with a 3D geometry interacting with its star. This is critical to understand how planets evolve and if gas giant planets can turn into bare rocks.”

The new findings provide a glimpse into the complex interplay between exoplanets and their stellar environments, with the potential to reshape our understanding of planetary evolution. By closely observing how helium, hydrogen, and other gases escape from these worlds, scientists can build better models to predict how planets transform over billions of years.

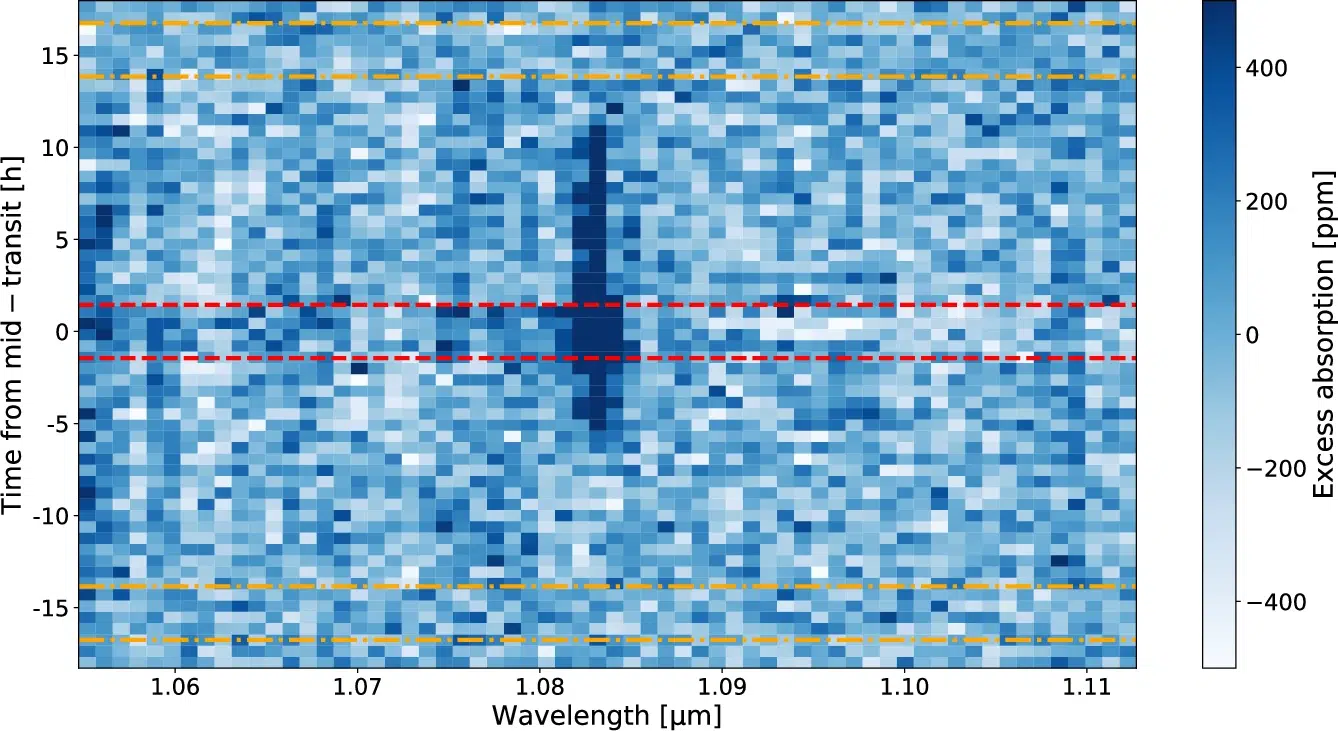

JWST/NIRISS excess absorption time series around the helium triplet relative to mid-transit time in the stellar rest frame. The red dashed lines represent the transit ingress and egress, while the two secondary eclipses ingress and egress are shown with the orange dashed dotted lines. Clear excess is detected as the dark blue region not only during the full transit, but also before and after, for a large fraction of the orbit, suggesting an extended outflow. The color scale was truncated to −500 to +500 ppm for better visualization purposes.

JWST/NIRISS excess absorption time series around the helium triplet relative to mid-transit time in the stellar rest frame. The red dashed lines represent the transit ingress and egress, while the two secondary eclipses ingress and egress are shown with the orange dashed dotted lines. Clear excess is detected as the dark blue region not only during the full transit, but also before and after, for a large fraction of the orbit, suggesting an extended outflow. The color scale was truncated to −500 to +500 ppm for better visualization purposes.

Credit: Nature Communications (Nat Commun)

Groundbreaking Instrumental Contribution

The discovery was made possible thanks to the continuous high-precision data from JWST’s NIRISS instrument, which is designed to probe the atmospheres of distant exoplanets. According to Louis-Philippe Coulombe, the study’s second author, “The continuous, high-precision data from NIRISS are what made this discovery possible.” The phase curve—used to observe a full orbit of the planet—allowed the team to access a wealth of information not just about the escaping atmosphere, but about other properties like the planet’s composition, climate, and energy budget. This breakthrough showcases the immense value of NIRISS, which has become a crucial tool for understanding exoplanet atmospheres.

Thanks to Canada’s contribution to the JWST, the country’s scientists have been able to push the boundaries of space exploration, providing critical insights into the dynamics of distant worlds. The results of this study underscore the significant role that Canada has played in shaping the global understanding of exoplanet science.

Implications for Exoplanet Research

The results from this study have profound implications for the future of exoplanet exploration. By observing WASP-121 b’s helium escape over a full orbit, the study sets the stage for future investigations of other distant exoplanets. Researchers are now poised to explore whether the double-tail structure discovered around WASP-121 b is a rare occurrence or if it’s common among other hot exoplanets. The ability to monitor these systems in real time offers new opportunities to investigate planetary evolution and the processes that shape these distant worlds.

In addition, this research could provide valuable insights into the “Neptune desert”—the scarcity of small, close-in gas giants. These planets may be the remnants of once-larger worlds whose atmospheres have been stripped away by the intense radiation from their parent stars. By examining how exoplanet atmospheres are eroded, astronomers could better understand the fate of these gas giants.

Nature Communications published the study, which explores the complex structures of atmospheric escape and highlights the need for more advanced simulations to accurately model these phenomena.