Seven decades have passed since the photographer Haga Hideo took his camera to Kagoshima’s Amami Islands, where he captured priceless images of older ways of life. His photos live on as historical records for the local residents, who recall those days as they find hints of the past—and images of their younger selves—in the Haga collection.

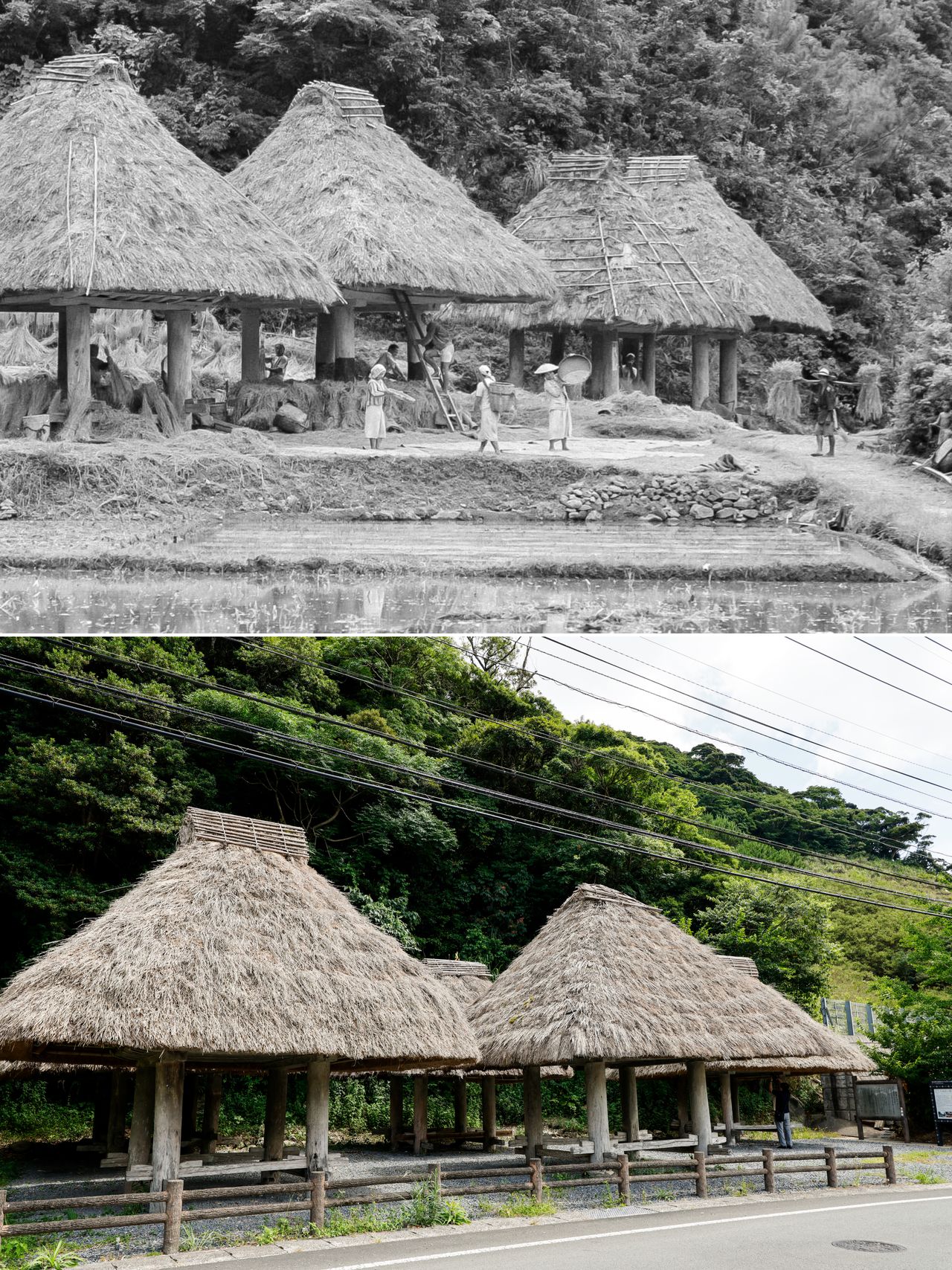

The Islands Where Time Stood Still

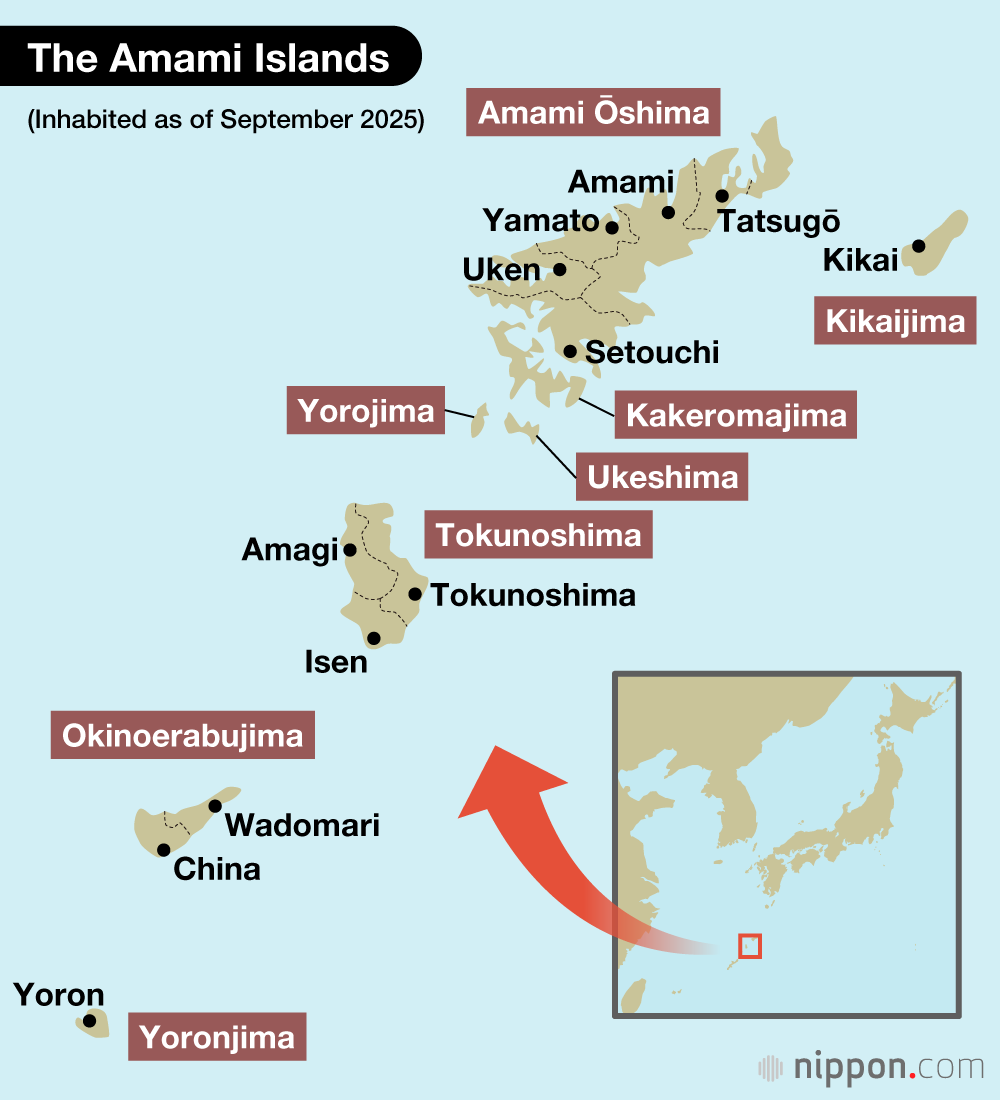

The Amami Islands, stretching southwest 370 to 560 kilometers from Kagoshima, include eight inhabited islands that are home to 100,000 people. A distinctive culture blending mainland Japan and Okinawan cultural influences has developed there over centuries.

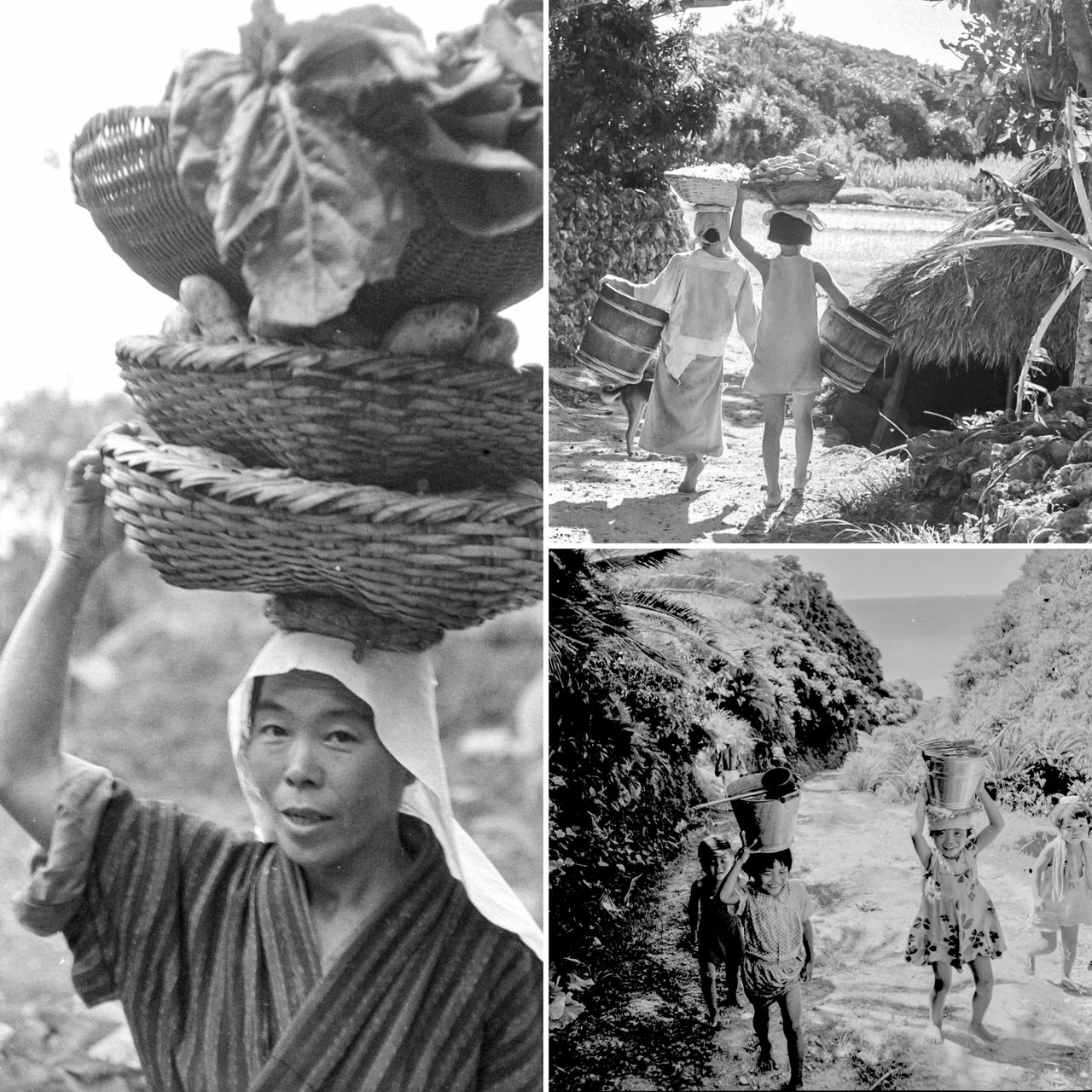

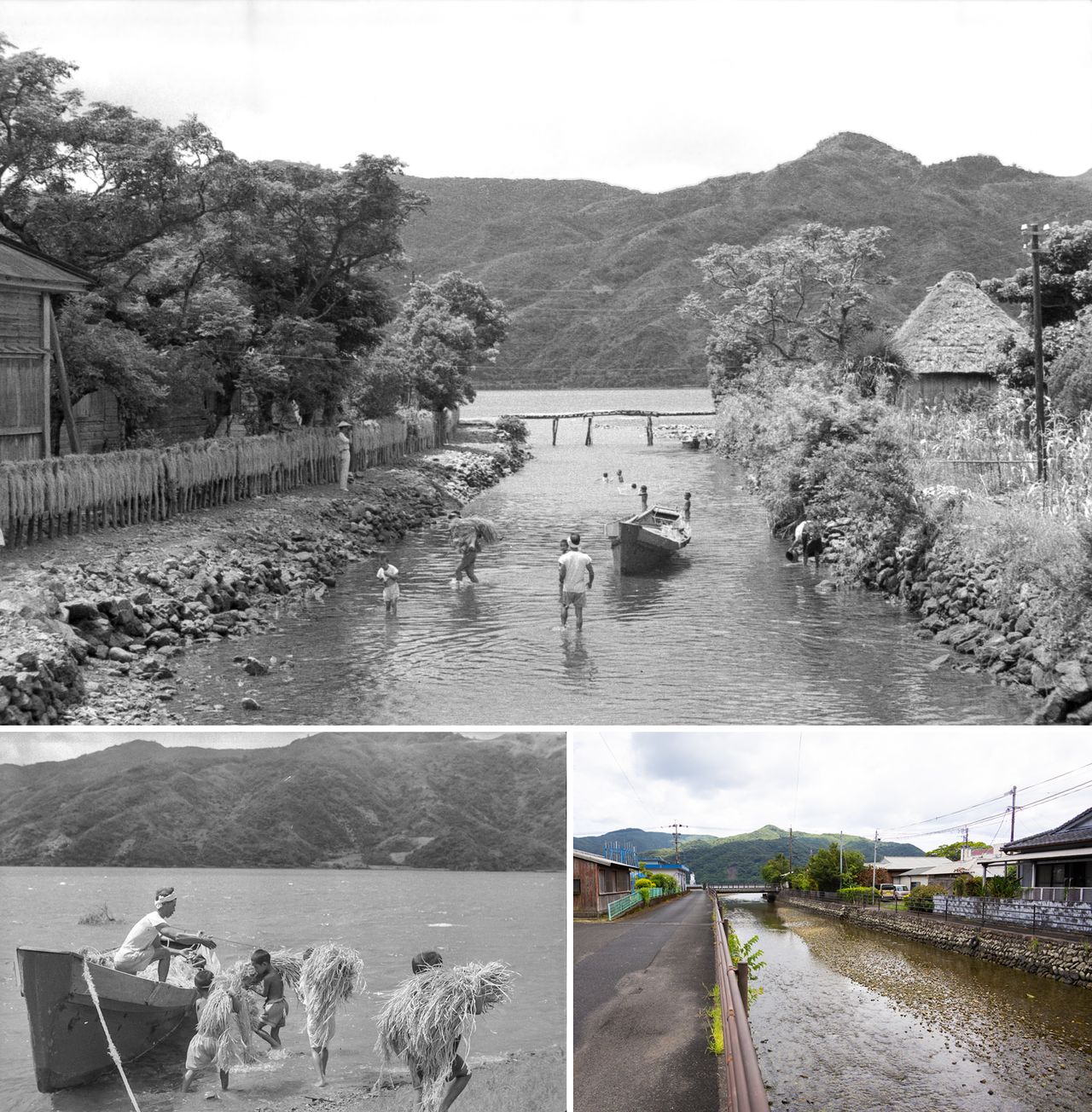

Up through the islands’ return to Japanese administration from US military rule in 1953, even as the high economic growth years were beginning on Japan’s main islands, life here retained its premodern rhythms. Women carried loads on their heads, rice was stored in elevated granaries, and mud baths were used to dye fibers to be woven into textiles, all vistas recalling times past. Extant customs—burials by exposure to the elements, ritual bone collecting and washing, spirit possession—were evidence of links with the cultures of the South Pacific.

Harpoon fishing at Okinoerabujima. (© Haga Hideo)

Women and children carrying loads on their heads. (© Haga Hideo)

The Federation of Nine Learned Societies, a cross-disciplinary body grouping scholars of folklore, religion, language, and other fields, conducted four joint surveys on the Amami Islands between 1955 and 1957, shortly after the islands’ reversion to Japanese rule. Haga Hideo, who later became a preeminent folklore photographer, was tasked with keeping a photographic record of the study. Over the study’s three years, he shot over 500 rolls of film, producing nearly 20,000 photos.

A group of storehouses in Yamato on Amami Ōshima. Preserved as a cultural asset, they huddle by the side of a road. (Top photo © Haga Hideo; lower photo © Haga Hinata)

Photos from 70 Years Ago Go Back Home

Until his death in 2022, Haga continued pursuing his life’s work, the photography of folkloric customs. He established the Haga Library, a photo collection that his son Hinata, a photographer himself, then took over. The photos taken during the Amami study 70 years ago are the oldest photographic record of life on the islands, and the Library regularly receives requests for photos taken in those days.

Film negatives deteriorate with age, however, and to preserve the collection, Haga Hinata and his supporters began planning to digitize the negatives in the hope that the collection would be used to teach local history. Nippon.com collaborated in the project and staff accompanied Haga Hinata in July this year when he traveled to Amami to donate the digitalized material.

The photo collection was donated to the Amami Museum in the city of Amami, the only general museum of the Amami Islands. Local photos in digitalized form of the village Uken, in the western part of Amami Ōshima, and of China and Wadomari on Okinoerabujima, where Haga had taken most of his photos, were also passed on to the respective municipalities.

Clockwise from top left: Haga Hinata, who donated his father’s photos to the Amami Museum; a presentation ceremony in Uken; representatives from China and Wadomari gather to receive the materials. (© Nippon.com)

An Uken resident in her nineties reminisces that “Haga-san often came to our house to drink with my husband.” In those days, every house in the village brewed their own liquor, “but with an eye on the visits by the tax inspectors, they were careful to locate their stills upriver, out of sight.”

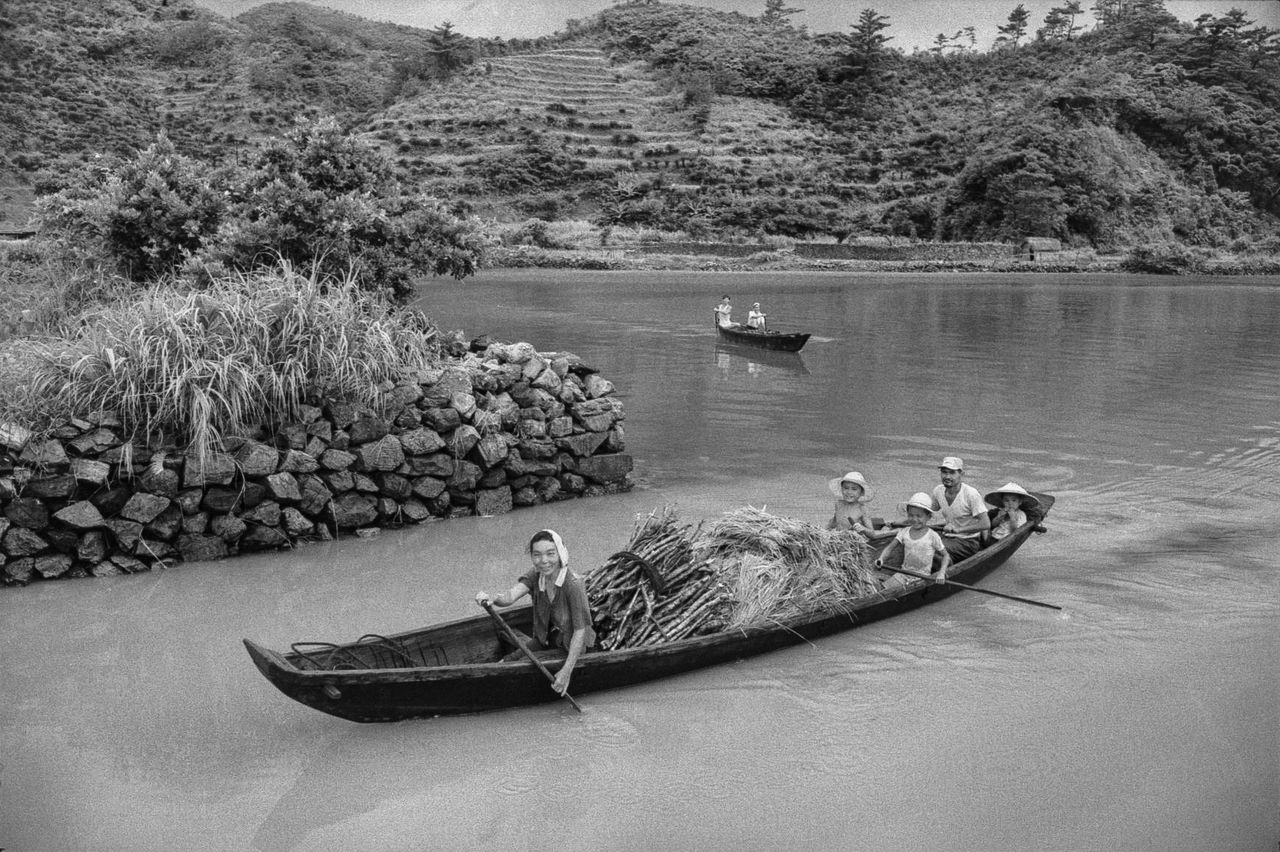

A family returning home after harvesting rice. (© Haga Hideo)

Another resident remembers the photo of a family rowing a small boat on the river. Cameras were rare in those days, making the family mother worry that Haga “might have been an official gathering evidence of illegal liquor brewing. Today, though, that photo is treasured by the family. Recalling with emotion the harsh conditions that necessitated the family taking their children with them to work in the fields, Haga Hideo once remarked that “Even so, they were happy because the family was together.”

In the postwar years, rivers were the main means of transportation in the village of Uken. Children also helped harvest the rice. (Top and lower left photos © Haga Hideo; lower right photo © Nippon.com)

Meeting Surviving Islanders

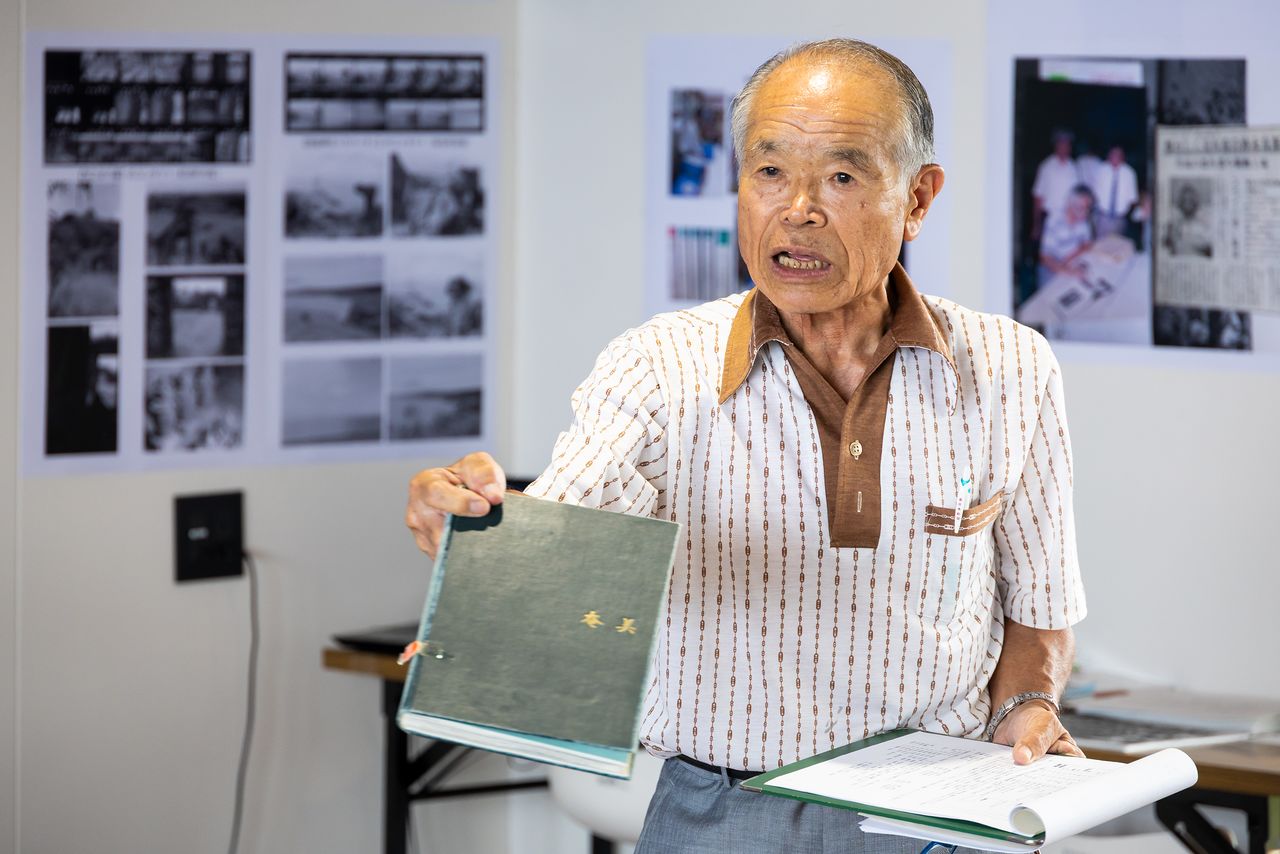

On Okinoerabujima, many members of the prewar generation are still living. Local historian Sakida Mitsunobu was overjoyed at the donation of the digitized photos, remarking: “They will be treasured by all of us. Nobody had any snapshots of those days, so this record of daily life is precious. I want to exhibit the photos so that the old-timers can see them and remember those earlier times.”

Sakida describes the photos, using the Federation of Nine Learned Societies report Amami as a reference. (© Nippon.com)

A New Year celebration then, and family members now. (Top photo © Haga Hideo; lower photo © Nippon.com)

During a recent visit, Sakida introduced Haga Hinata and his party to some of the old-timers, who recounted their recollections.

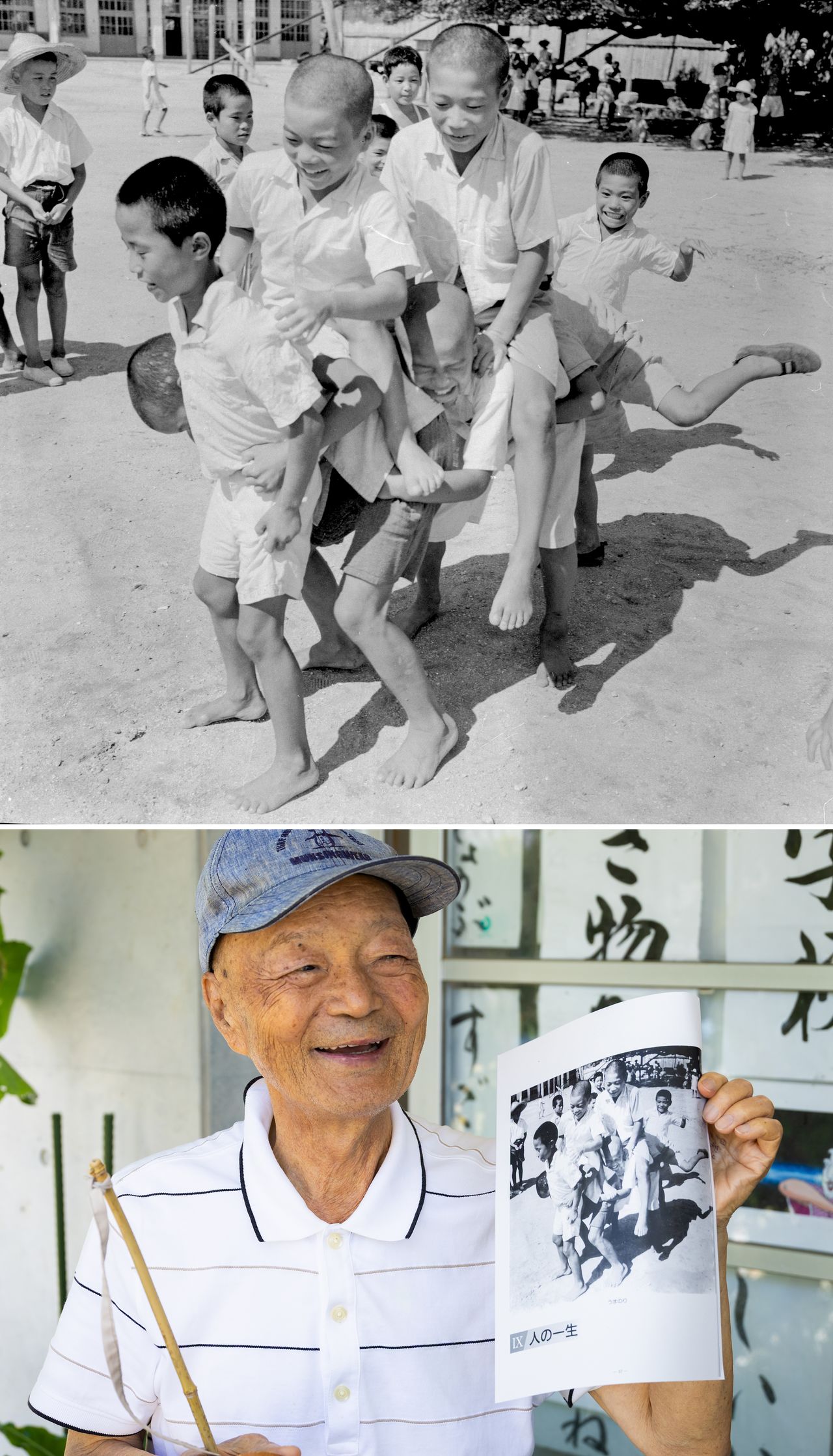

The “horse rider” second from left at the top laughs: “You can see the resemblance, don’t you think?” (Top photo © Haga Hideo; lower photo © Nippon.com)

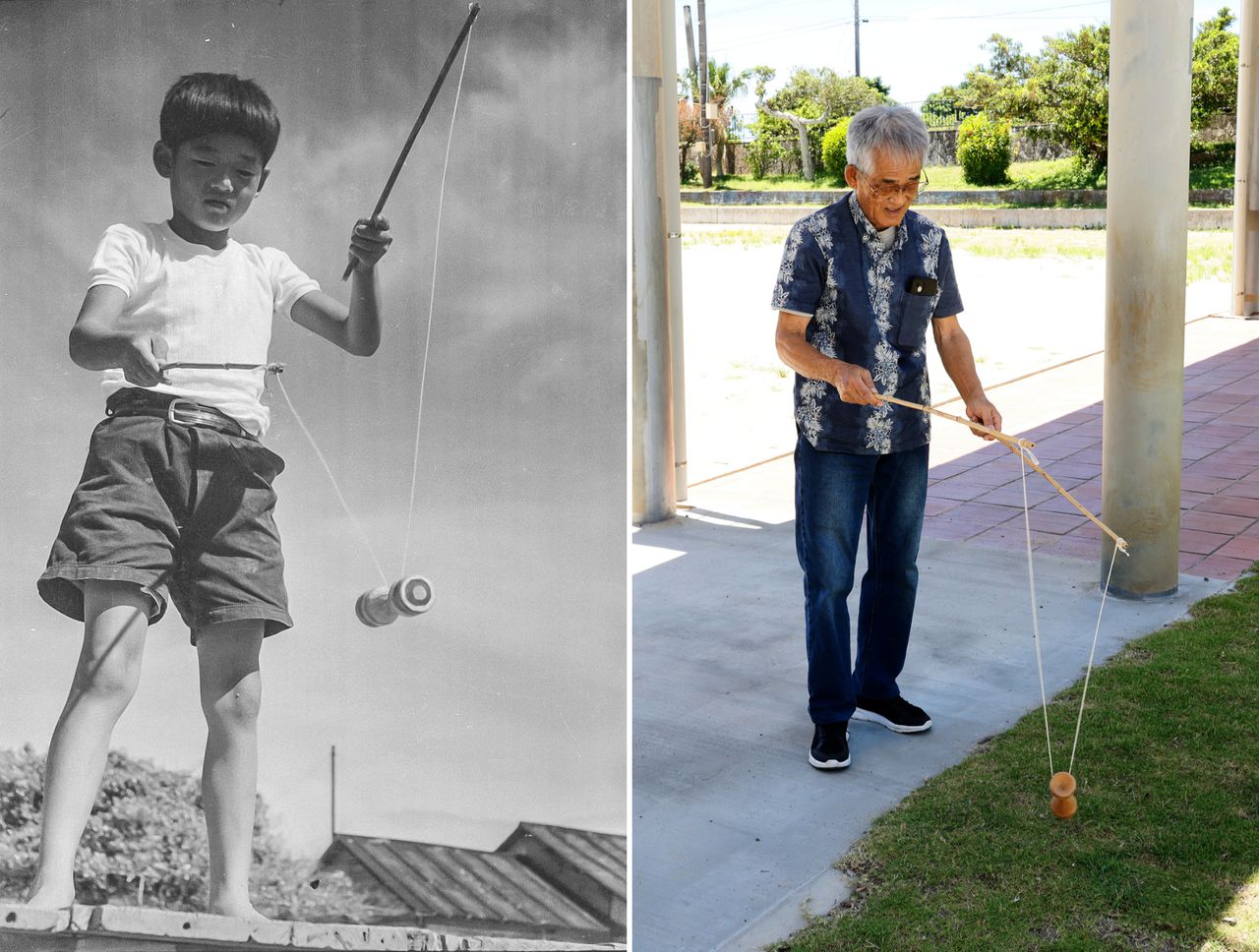

A man tries his hand at byābōru, a local toy similar to a yo-yo that he played with 70 years ago. (From left, © Haga Hideo; © Haga Hinata)

Photos of children’s play show elementary school children in the schoolyard. The party gave the man who demonstrated his yo-yo skills a copy of the photo, which he was delighted to receive.

From top: Children carrying an organ into the new Kunigami elementary school building; part of the group sits reminiscing over the photo. (Top photo © Haga Hideo; lower photo © Haga Hinata)

The school building is new, but the banyan tree, reputedly Japan’s finest, is still going strong in the schoolyard. (Top photo © Haga Hideo; lower photo © Nippon.com)

Perusing group photos of students at Kunigami elementary school, women exclaim excitedly: “Oh, that’s me!” or “Look! That one’s my husband.”

One photo shows yāmin, the first meeting of the families of prospective marriage partners at the groom’s home. The bride, in the front row with a bandeau in her hair, recalls: “In those days, there was no television or other entertainment, so the whole neighborhood turned out to watch. I was dreadfully embarrassed.” Marriage was an important event for the families and also a major social occasion for the village.

On the big day, the bashful bride looked down the entire time, flustered by the onlookers. “Someone even brought a goat along,” she laughs. (Top photo © Haga Hideo; lower photo © Nippon.com)

In one of Haga Hideo’s best-known photos, an old man entertains children with folk tales under papaya and passion fruit trees. Taira Maenobu, who could recite 70 of the local oral traditions, was the island’s best storyteller; he was interviewed by Seki Keigo, a researcher of oral traditions, during field studies on Amami in the 1950s.

Matsumura Yukie, a distant relative of Taira’s, is trying to sustain shimamuni, as the local tongue is called, through picture books and other resources. Shimamuni is one of the Kunigami languages, which is listed in UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Since 2019, activities to preserve the language—compilation of a dictionary, lectures, and performances of shimauta local songs and plays—have been ongoing under the auspices of the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics. Matsumura says that Haga’s photographic record motivated her to work to preserve the language and that she intends to utilize the collection to further her activities.

Subtropical vegetation flourished then, as it does now. The storyteller Taira Maenobu shares tales with island youth (left, © Haga Hideo); the boy perched in the tree, now grown, stands on the left, with Matsumura Yukie at center (right, © Nippon.com).

Memories of the Past Connect with the Future

The islands’ chalky soil made rice growing in muddy paddies arduous work. (© Haga Hideo)

A man clambers up a ladder hoisting a 60-kilogram bale of rice to store in an elevated granary. The ladder, with footholds hewn into a log, closely resembles specimens excavated at Toro, a Yayoi period (ca. 300 BCE–300 CE) archaeological site in Shizuoka Prefecture. (© Haga Hideo)

Today, agriculture on Okinoerabujima centers on cash crops such as sugar cane and lilies, but in the past, rice paddies dotted the landscape. The paddies were worked using hoes with wooden “teeth,” and rice bales were stored in thatched-roof elevated granaries.

One of those granaries was moved a folk museum in Wadomari and reconstructed there. Inside, old farming implements and other cultural artifacts are displayed, along with photos by Haga Hideo recording now long-lost farming practices. The granary’s ladder is similar in construction to those used during the Yayoi period (ca. 300 BCE–300 CE), when wet rice cultivation became established in Japan. Hideo, who made it his life’s calling to photograph rites associated with tanokami rice deities, no doubt recalled the timeless farming scenery of ancient times as he pressed his camera’s shutter button.

The museum displays everyday articles of yesteryear. A granary and ladder are also preserved there. (© Nippon.com)

In another famed Haga shot, women bearing buckets on their heads ascend the stone stairs out of the pitch-dark Sumiyoshi Kuragō limestone cave. While the shot brings to mind an art photo, it is a reminder of a hard life without running water.

Okinoerabujima is an island made of limestone crisscrossed with subterranean rivers. Springs well up everywhere and the ponds created were the communities’ shared resource. It was the job of women and children to fetch water and wash belongings there. Children learned to balance loads on their heads early on. Any spilled water would have to be collected again, so everyone was keen to learn to carry their precious cargo properly.

Even today, there is a school sports day head-carrying competition, and the children learn about their forebears’ way of life with tours of the Kuragō cave. A signboard outside the cave displays Hideo’s photos.

Fetching water was hard work. The Kuragō cave has been preserved as a site where children learn about local history. (Left and top right photos © Haga Hideo; lower right photo © Nippon.com)

One of the spring-fed ponds, Wanjo, is now a park. Inhabitants used the water upstream for drinking. Further downstream, it was used for bathing, laundering, and watering livestock. The ponds were also lively social centers. (Top photo © Haga Hideo; lower photo © Haga Hinata)

Economic development arrived on the Amami Islands in the years following the Learned Societies’ field studies. Life became easier, but the old ways and the local tongue were abandoned.

Of his trip to Amami, Haga Hinata says: “Viewing the landscapes that my father captured in his photos and meeting some of the people who appeared in them made me feel as though I had stumbled into a fairytale world. It was a wonderful trip, and I feel that the old ways of life eked out in harsh conditions contributed to the resilience of the people living on the islands today.” One hundred years from now, Haga Hideo’s photos will no doubt continue to show the unspoiled landscape of the 1950s isles as clearly as they do now.

Haga Hideo (center) helps push a loaded wagon on Okinoerabujima. (© Haga Hideo)

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting and text by Nippon.com. Banner photo: Children in the 1950s at Okinoerabujima’s Kunigami elementary school, then [© Haga Hideo] and now [© Nippon.com].)