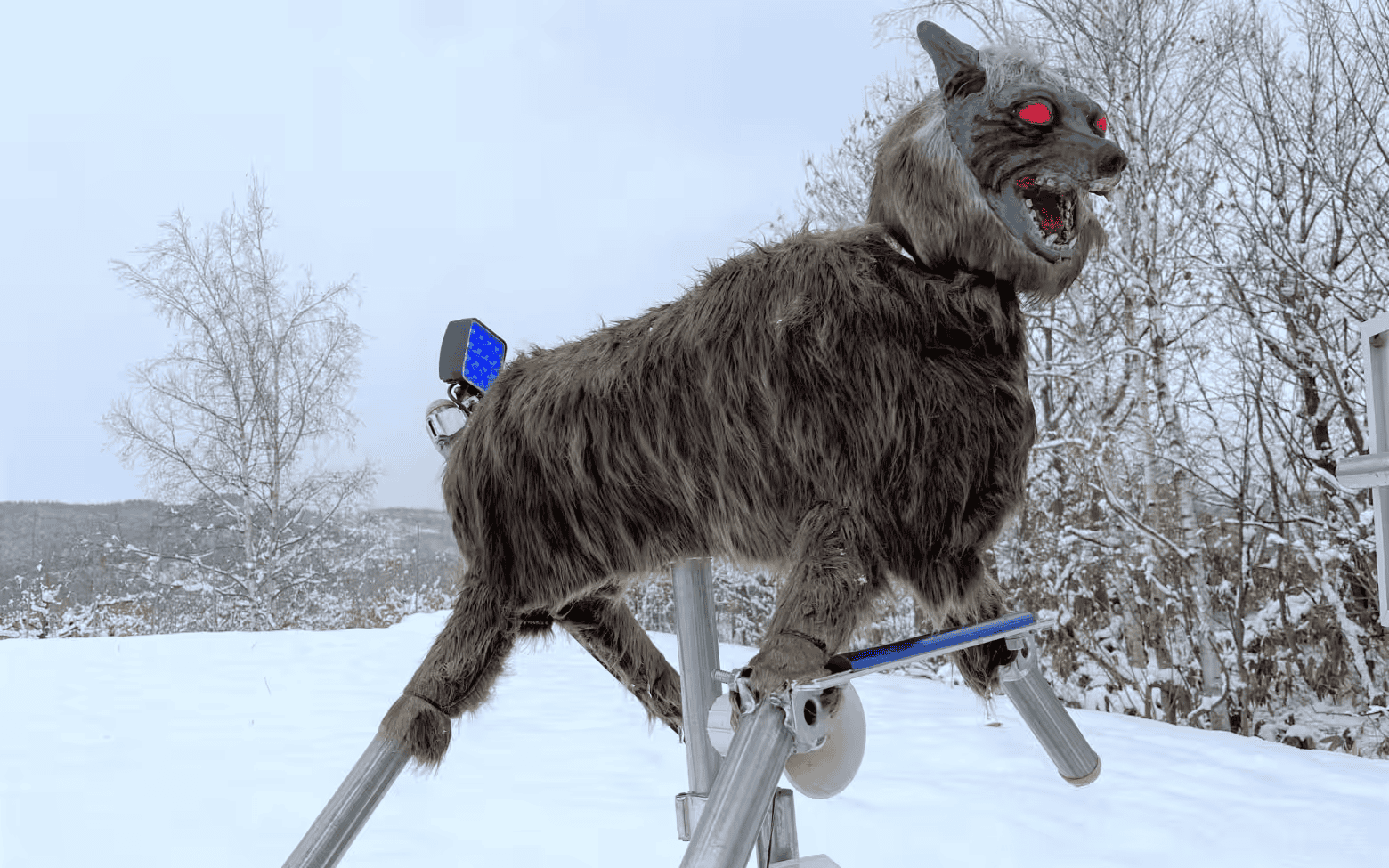

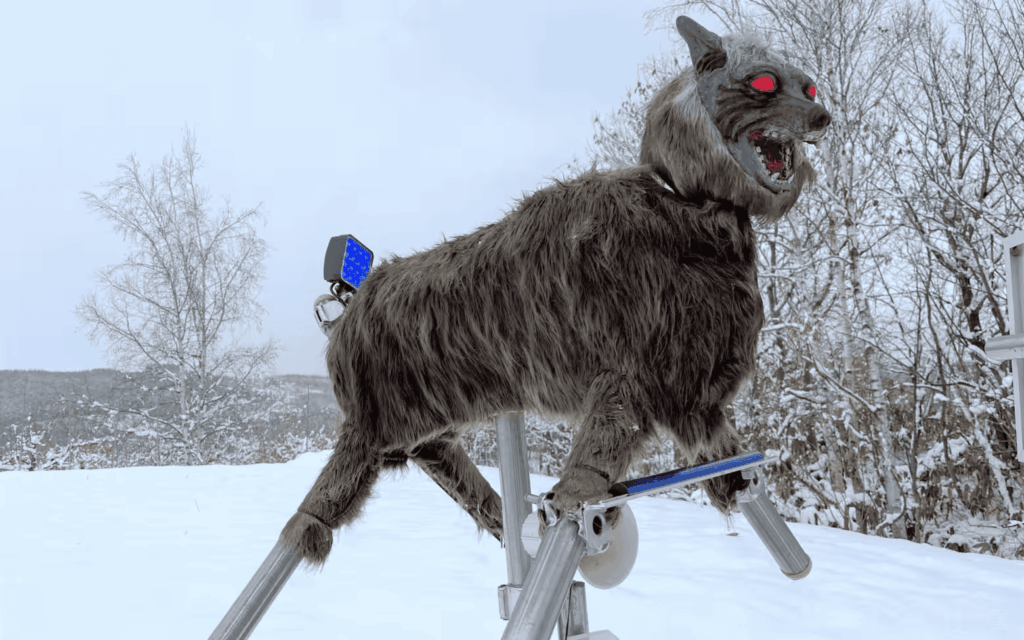

Ohta Seiki’s Monster Wolf detects wild animals with an infrared sensor and scares them away with flashing lights and loud noises. (Photo by Kotose Hamano)

Ohta Seiki’s Monster Wolf detects wild animals with an infrared sensor and scares them away with flashing lights and loud noises. (Photo by Kotose Hamano)

Record-high bear attacks in Japan are forcing a dramatic change in tactics, pitting humans against wildlife in an escalating conflict. But the latest hero of this high-stakes ecological drama isn’t a crack team of hunters or a new kind of fence. It’s a faux-fur, mechanical sentry with glowing red eyes: the “Monster Wolf.”

This bizarre, yet effective, robot is the brainchild of a small factory in Hokkaido, and it’s suddenly become the unexpected star in the nation’s fight to create a crucial “buffer zone between wildlife and people,” as the number of bear incidents skyrockets.

Once dismissed as a gimmick, the so-called Monster Wolf is now spreading across the country, deployed in forests, orchards, and villages where people and bears increasingly collide.

A Mechanical Predator With a Purpose

The Monster Wolf comes from Ohta Seiki, a precision machining company based in Hokkaido. The device bristles with LEDs, sensors, speakers, and faux fur. When its infrared sensors detect movement, it responds fast. Its eyes glow red, its head turns “menacingly from side to side,” and blue LED lights flash on its body.

There’s of course sound. Or noise, better said. It emits sounds “as loud as a car horn,” set at 90 decibels. The robot can emit around 50 different noises at random, including animal howls and human voices. Randomization matters because animals can habituate to predictable threats.

“Bears are very cautious animals and often act alone,” Yuji Ota, president of Ohta Seiki, told Kyodo News. “When there is a loud noise, they would think there is something there and would not come close.”

When the Monster Wolf debuted in 2016, many people laughed. I did too for that matter, when I first wrote about it for ZME. Electric fences were the standard defense against wildlife, and the robot’s appearance was widely mocked as foolish. But it just works. Farmers reported fewer intrusions, maintenance was simple, and the “wolves” kept working through harsh northern winters.

Today, about 330 Monster Wolves are operating across Japan, guarding farms, hiking trails, and animal corridors. Demand has surged as bear attacks have risen, with company inquiries tripling in recent months.

“It’s been a success. To date, no one has questioned its effectiveness, nor have we faced any returns due to dissatisfaction,” Ota told ABC News in 2023.

In fact, interest in robot wolves has gone international. Ohta Seiki has fielded roughly 10 overseas inquiries, including one from India asking whether the robot could deter elephants.

Bears, Buffer Zones, and the Limits of Fear

Japan’s bear problem is not new, but it is intensifying. According to NHK, bear attacks injured 235 people and killed 13 across 21 prefectures in 2024, with Akita reporting the highest number of incidents. In October alone, seven people died in bear maulings near populated areas, with 13 fatal attacks in total over the past year, according to NBC News. The outlet added that Japan has recorded 200 injuries connected to bear attacks since April 2025.

Some attacks are happening even in winter, when bears usually hibernate. A December attack in Nagano was the first of its kind in that region since 1977.

Why the sudden, terrifying rise? For one, there’s competition for food. Beechnuts, a crucial autumn food source for Asiatic black bears, follow a boom-and-bust cycle. A poor harvest often pushes hungry animals into towns and farmland. Researchers warn that after a projected plentiful year in 2026, another shortage is likely in 2027.

The Washington Post also cited a declining human population in Japan’s more rural areas as another factor contributing to the bear attack issue, noting that less human activity gives wild bears more room to expand their range.

Hokkaido, with its vast wilderness, shows how quickly these pressures add up. In fiscal year 2023, officials captured 1,804 brown bears — about twice the previous year and the highest number since 1962. Wildlife damage in the prefecture reached more than 5.6 billion yen ($USD 36 million) in 2022, accounting for over a third of Japan’s total losses due to wildlife.

These trends have pushed authorities toward drastic measures. In Akita, the military was deployed to help trap bears. National rules were revised to allow riot police to shoot bears in certain situations, a power once limited only to licensed hunters.

Against this backdrop, the Monster Wolf at least offers deterrence rather than extermination.

“I think it’s much more cost-effective to threaten with a machine and drive it away from the village than the cost of a lot of people going out and exterminate it,” Ota said.

But experts caution that fear-based technology has limits. Animals learn.

“While the sudden lights and noises can startle wildlife, many animals learn and adapt. Once a sizeable segment of any species realises the lack of actual harm, its deterrent effect may wane,” said zoologist Nobuyuki Yamaguchi of the University of Malaysia, Terengganu, in an interview with ABC News.

The Evolving Predator-Prey Dynamic

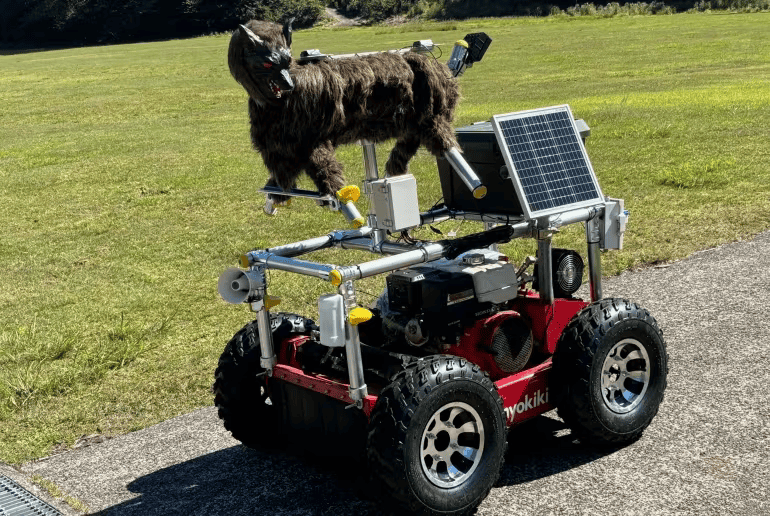

Ohta Seiki is testing self-driving of a vehicle carrying “Monster Wolf” on top. Credit: Wolf Kamuy.

Ohta Seiki is testing self-driving of a vehicle carrying “Monster Wolf” on top. Credit: Wolf Kamuy.

Yamaguchi also pointed to deeper evolutionary dynamics. “For wildlife we humans are the scariest monsters — much more so than even is the mighty lion!” he said. “Brown bears and wolves have evolved almost next to each other, and hence, the brown bear possibly ‘knows’ what the wolf is, and vice versa.”

That insight helps explain why the robot works at all — and why it might eventually fail if overused.

Researchers and conservationists argue that technology must be paired with landscape planning. Buffer zones, controlled animal corridors, and barriers like electric fences still matter.

“Zoning is important for the protection of humans from brown bears,” said Toshio Tsubota, a bear biologist at Hokkaido University. “Such steady efforts as controlling encroachment routes of animals and installing electric fences will be necessary.”

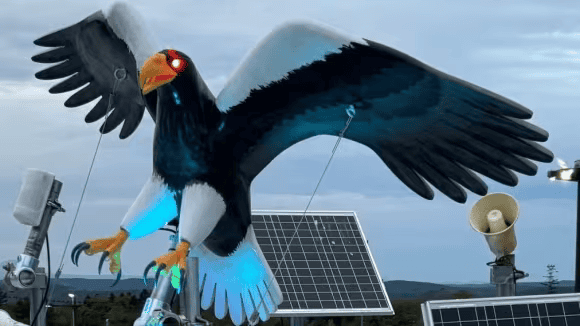

Ohta Seiki is developing “Monster Eagle” which can help prevent damage from crows and other birds. Credit: Wolf Kamuy.

Ohta Seiki is developing “Monster Eagle” which can help prevent damage from crows and other birds. Credit: Wolf Kamuy.

Ohta Seiki seems to agree. The company is testing mobile and self-driving versions of the Monster Wolf, including vehicles developed with Suzuki and researchers from the University of Tokyo. It is also building new robotic predators, like a “Monster Eagle” to scare crows in urban areas.

So, the robot wolf is not a silver bullet for wildlife threats. It is more of a stopgap — one more tool in a rapidly evolving effort to manage the boundary between human systems and wild ones.

But for now, as bears test the edges of Japan’s towns and farms, a mechanical howl in the night may be enough to send them back into the woods.