RansomHouse is a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) operation run by a group that we track as Jolly Scorpius. Recent samples of the associated binaries used in RansomHouse operations reveal a significant upgrade in encryption. This article explores the upgrade of RansomHouse encryption and the potential impact for defenders.

Jolly Scorpius uses a double extortion strategy. This strategy combines stealing and encrypting a victim’s data with threats to leak the stolen data.

The scale of the group’s operations is significant. At the time of this article, at least 123 victims were listed on the RansomHouse data leak site as having their data disclosed or sold since December 2021.

This group has disrupted critical sectors including healthcare, finance, transportation and government. The consequences of these intrusions include significant financial losses, major data breaches and erosion of public trust in the affected organizations.

To better understand RansomHouse operations, we review its attack chain. We also examine the upgrade to this ransomware’s encryption from a simple, single-phase linear technique to a more complex, multi-layered method.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats described in this article through the following products and services:

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

Actor Roles and the Attack Chain

Despite Jolly Scorpius positioning itself as a group that exposes corporate vulnerabilities, its actions reveal a straightforward extortion business. To better understand its RansomHouse operations, we can identify the specific actor roles, discern separate phases of the attack chain and determine how the roles and phases relate to each other.

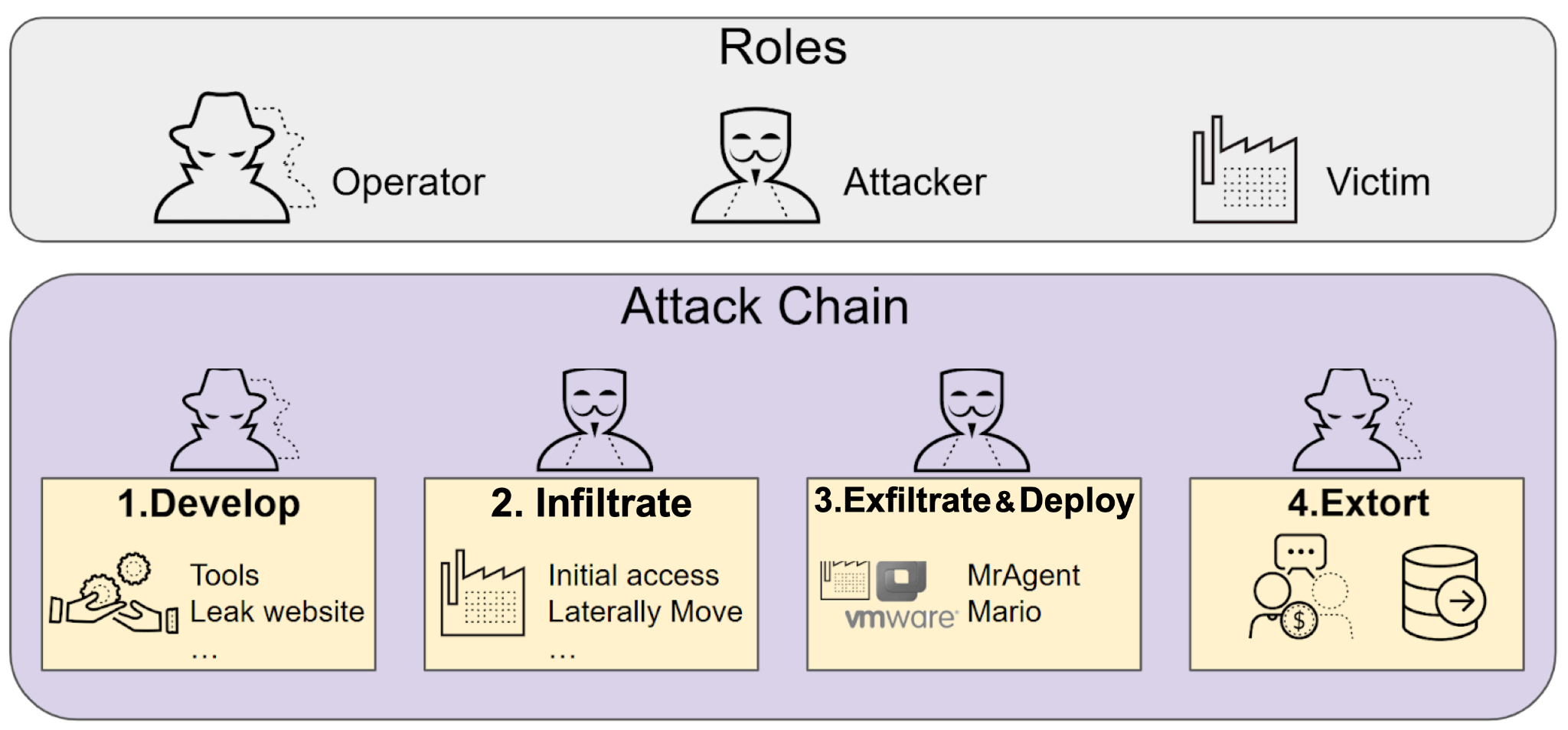

Figure 1 illustrates these roles and their positions in the attack chain.

Figure 1. Actor roles and how they relate to phases of the RansomHouse attack chain.

Figure 1. Actor roles and how they relate to phases of the RansomHouse attack chain.

The RansomHouse attack chain involves three distinct roles:

Operator: Operates the RaaS

Attacker: Deploys the ransomware

Victim: Targeted by the attacker

Operators are responsible for establishing and maintaining the RaaS, including the development of tools for data encryption and other functions. Individuals in this role manage the data leak site and architecture for victims to negotiate ransom payments. This includes managing the cryptocurrency wallets for ransom collection and laundering.

Attackers are typically known as affiliates because they are separate threat actors from the operators. As ransomware services rise and fall, attackers can switch their affiliation to different RaaS groups. Attackers are responsible for gaining initial access, moving laterally, exfiltrating data and deploying the ransomware.

Attackers for RansomHouse are known for targeting VMware ESXi infrastructure, a common enterprise-grade hypervisor platform. RansomHouse attackers specifically target ESXi because compromising this platform allows them to encrypt dozens or hundreds of virtual machines at once, causing maximum operational disruption.

The attack chain reflects a multi-faceted strategy to pressure RansomHouse victims. This strategy involves harvesting sensitive information, encrypting select data, publishing victim identities and threatening to release their sensitive data. The RansomHouse attack chain can be broken into four phases:

Develop

Infiltrate

Exfiltrate and deploy

Extort

Each phase involves at least one of the three roles.

In this phase, RansomHouse operators function as the backend providers, responsible for developing all aspects of the RaaS. Crucially, the operators typically do not conduct the initial intrusions. Instead, they rely on their affiliates (i.e., the attackers) to leverage the RaaS services developed in this phase.

In this phase, attackers compromise victims through spear phishing emails or other social engineering techniques. In addition to email, initial access vectors include vulnerable systems in a victim’s environment that attackers can compromise through zero-day or other exploits.

After achieving initial access, attackers typically use third-party tools and frameworks to explore the victim’s network. The remainder of the infiltration phase includes reconnaissance to map the environment, privilege escalation, lateral movement and identifying valuable or sensitive information.

Phase 3: Exfiltrate and Deploy

Once attackers affiliated with RansomHouse have infiltrated a victim’s environment, they exfiltrate sensitive data and deploy the ransomware. Typical data exfiltration techniques involve file compression and file transfer utilities, and attackers usually send data to servers under their control.

The RansomHouse RaaS uses a modular architecture that consists of two components:

Management tool

Encryptor

RansomHouse uses a management tool called MrAgent, designed to automate and track ransomware deployments across different hypervisor systems in an ESXi environment.

RansomHouse uses an encryptor known as Mario. After encrypting files, Mario drops a ransom note that contains instructions on how victims can recover their data.

Once a victim’s data has been stolen and encrypted, the attack chain transitions to the extortion phase. RaaS operators are generally responsible for this phase, which often involves negotiations via dedicated chat rooms. Operators validate their threats through strategic information disclosure on platforms like Telegram and the RansomHouse data leak site.

Now that we better understand the RansomHouse attack chain, let’s review how the components of this ransomware are used in attacks.

RansomHouse Components Used in Attacks

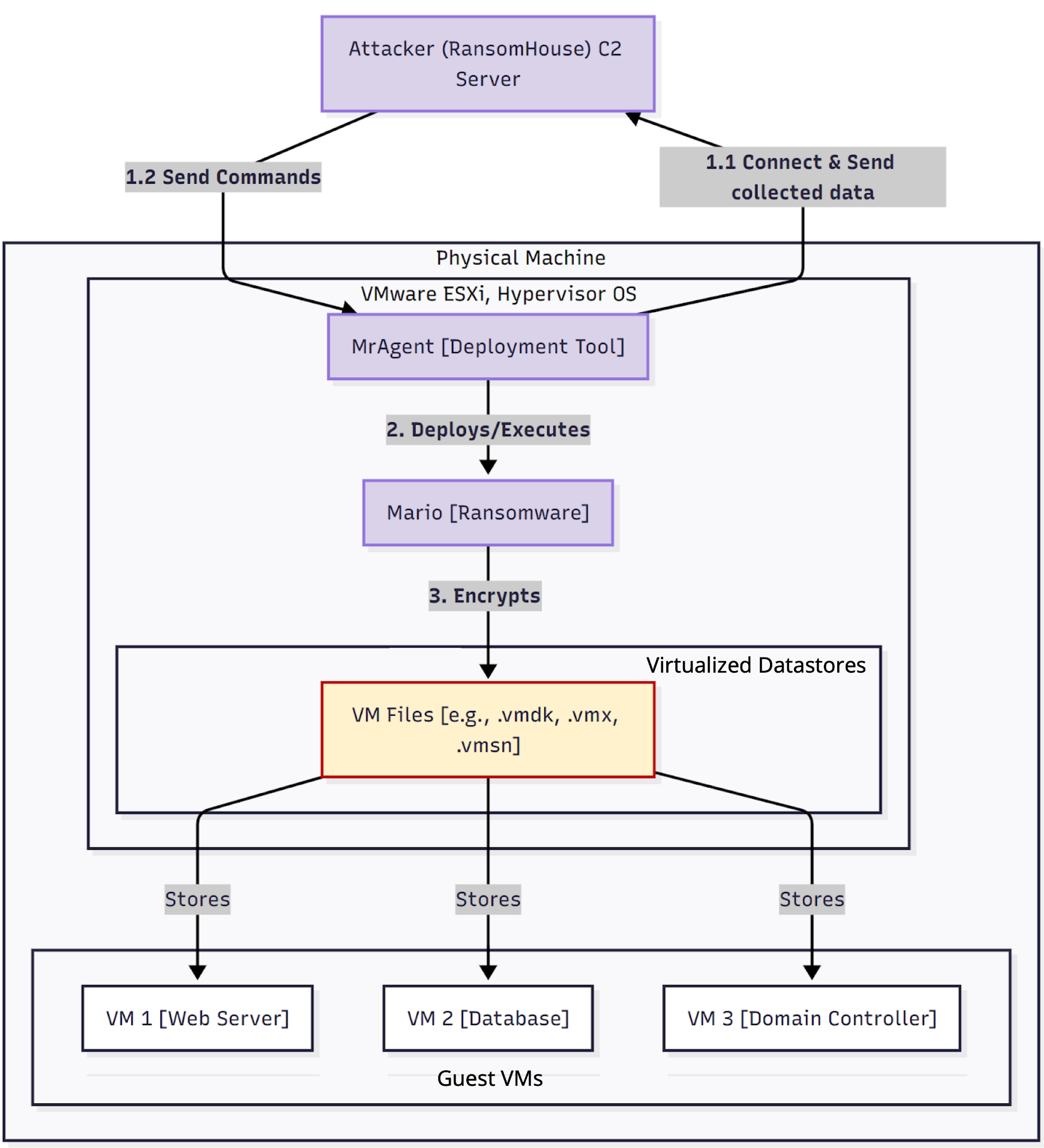

The two components of this ransomware (i.e., MrAgent and Mario) are specifically engineered to compromise virtualized environments. Figure 2 illustrates how these tools are used in a RansomHouse attack in an ESXi network.

Figure 2. Flow chart of how RansomHouse components are used in an ESXi environment.

Figure 2. Flow chart of how RansomHouse components are used in an ESXi environment.

After infiltrating the environment, an attacker deploys MrAgent onto the victim’s ESXi hypervisor. MrAgent establishes a persistent connection to the attacker’s command-and-control (C2) server.

Attackers then issue commands from the C2 server to MrAgent for further operations like data exfiltration. After the data is exfiltrated, attackers instruct MrAgent to download and execute the Mario encryptor, which runs directly on the hypervisor to encrypt virtual machine (VM) files.

Since MrAgent is the first component in the attack, let’s review how it works.

MrAgent: The RansomHouse Deployment Tool

As the primary tool for RansomHouse operations, MrAgent provides attackers with persistent access to a victim’s environment and simplifies managing compromised hosts at scale. This management is accomplished through various functions of the tool.

The main functions of MrAgent are:

Acquiring host identifiers

Acquiring the host’s IP address

Disabling the firewall

Communicating with the attacker’s C2 server

While an analysis by Trellix has documented the commands MrAgent uses for these functions, we can review them to better understand its operations.

Commands for acquiring host identifiers are as follows:

For the hostname: uname -a

For the MAC address: esxcli –formatter=csv network nic list

The command to acquire the host’s IP address is:

esxcli –formatter=csv network ip interface ipv4 get

The command to disable the firewall is:

esxcli network firewall set –enabled false

MrAgent’s function to check for connectivity to the C2 server runs in an infinite loop. During these connectivity checks, MrAgent can receive various instructions from the C2 server. Table 1 lists examples of these instructions and their function.

Instruction

Function

Abort

Aborts the start of encryption if the hypervisor is in its delay phase after a reboot

Abort_f

Kills threads spawned by MrAgent

Config

Overwrites the local configuration used for ransomware deployment

Exec

Starts the ransomware deployment, changing the root password, disabling vCenter remote management via /etc/init.d/vpxa stop and starting the encryption of VMs

Info

Retrieves ESXi host information

Run

Executes arbitrary commands on the ESXi host by writing to the file ./shmv

Remove

Removes content from the ESXi host by executing the command rm -rf [filename or path]

Quit

Kills and removes the MrAgent binary using rm -f

Welcome

Sets the ESXi welcome message on the host via esxcli system welcomemesg set -m=”[text of message]”

Table 1. Examples of MrAgent instructions from an attacker’s C2 server.

These functions enable MrAgent to deploy the Mario encryptor.

To impede reverse engineering, the MrAgent binary is sometimes modified with junk code, but this basic obfuscation does not alter its fundamental operations. For state management of the compromised environment, MrAgent uses two internal JSON structures to store its runtime configuration and status, with access synchronized by a mutex.

Mario: The RansomHouse Encryptor

MrAgent deploys Mario to accomplish the operation’s core function of encrypting critical VM files in the ESXi hypervisor. Our research uncovered two distinct versions of Mario that reveal an evolution in its encryption methods.

Both versions follow the same overall execution flow:

Create the ransom note

Target file extensions

Encrypt files

Report statistics

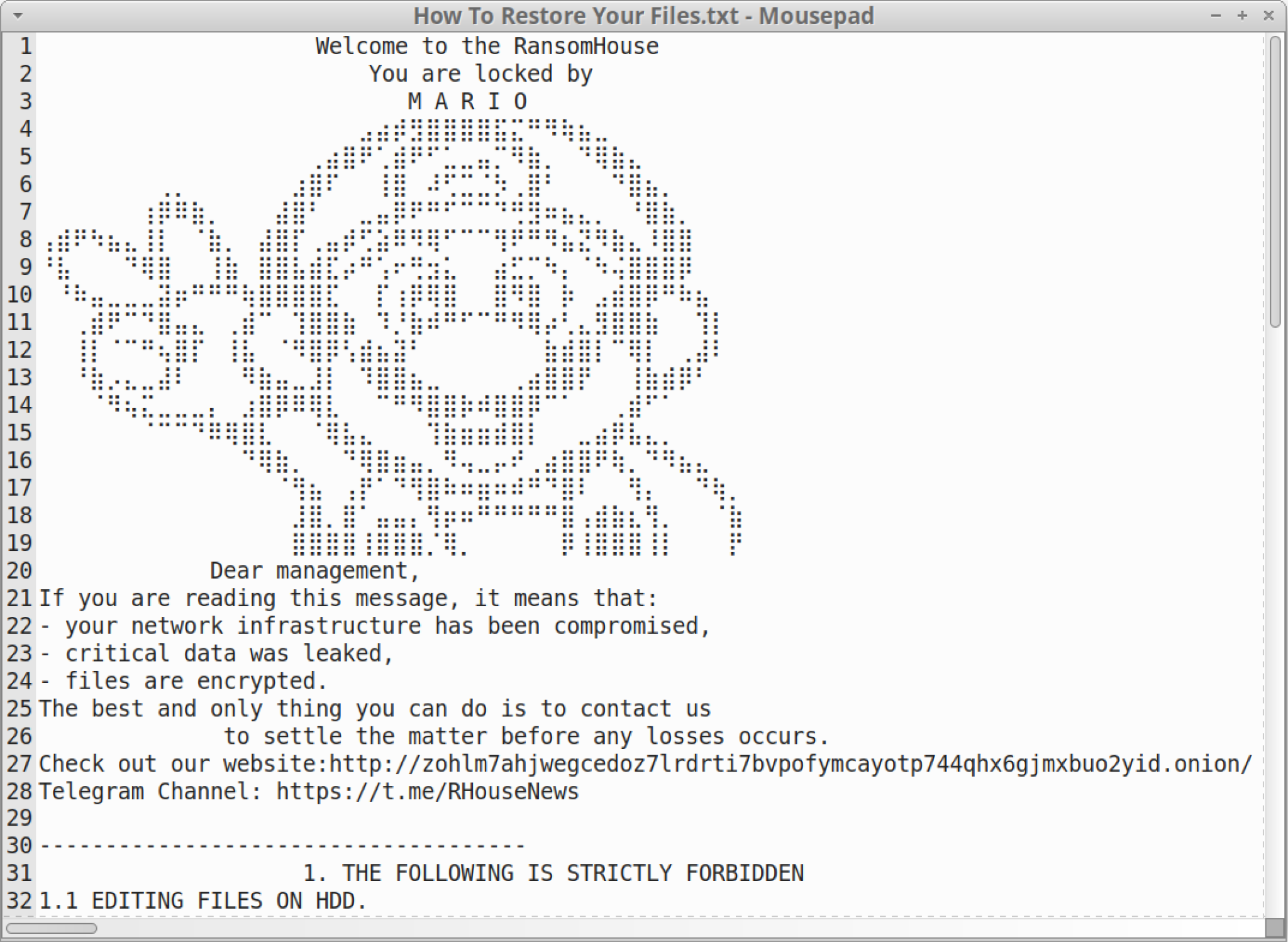

The first step in Mario’s execution flow is creating a ransom note. The ransom note is named How To Restore Your Files.txt and is located in the directory of any files that Mario encrypts.

Mario opens the ransom note in write mode and saves text to the file that provides instructions for victims to recover their files. Figure 3 below shows an example of this note.

Figure 3. Example of a ransom note generated by a Mario sample.

Figure 3. Example of a ransom note generated by a Mario sample.

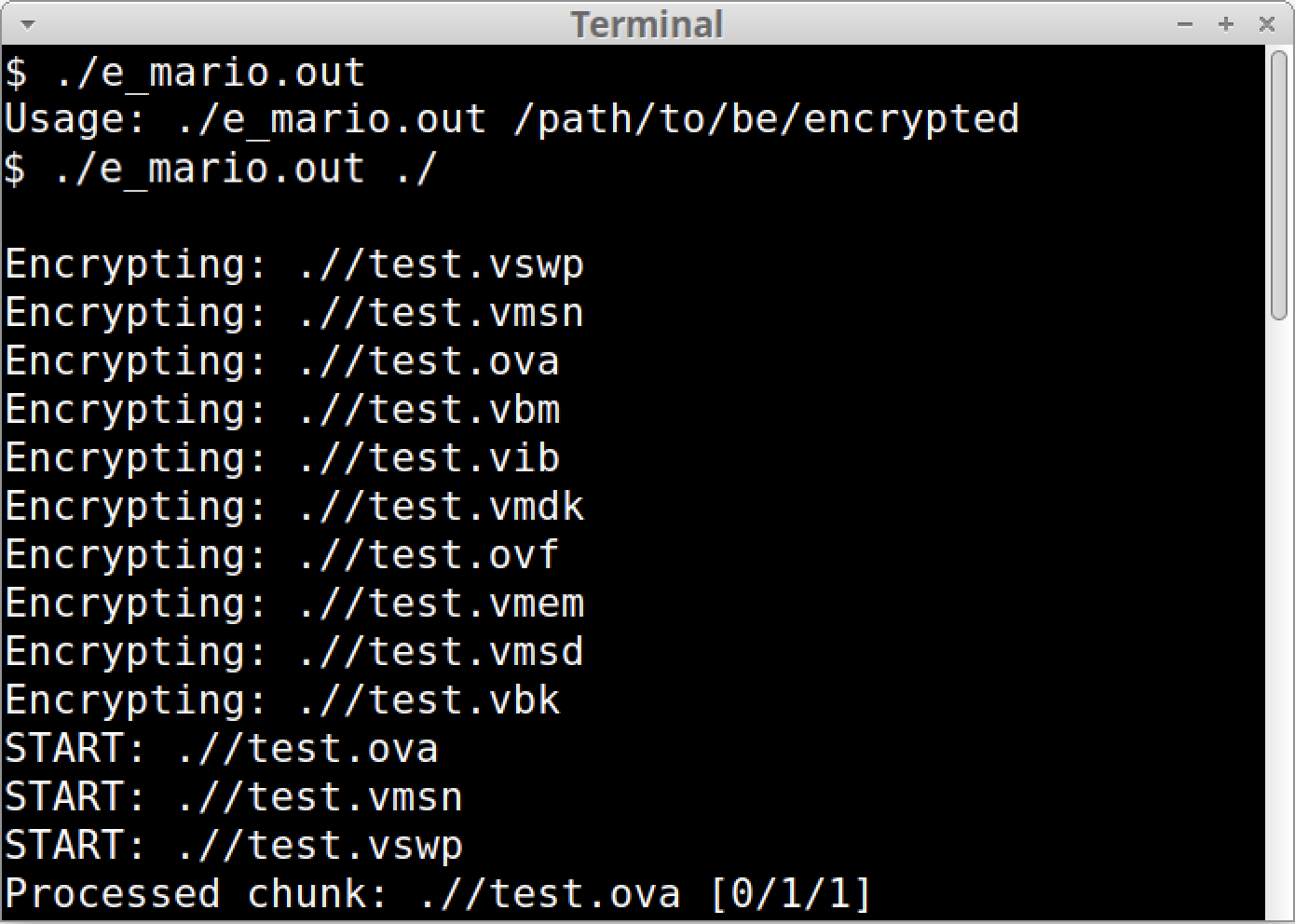

Targeting File Extensions

The next step is directory traversal and extension targeting. Mario requires attackers to specify the directory path of the files to encrypt. Within the specified directory, Mario targets virtualization files based on the filename extensions listed in Table 2.

Extension

File Description

ova

Open Virtual Appliance (OVA): a single-file distribution of the OVF file package

ovf

Open Virtualization Format (OVF): an open standard for packaging and distributing virtual software

vbk

Veeam Backup (VBK) file: stores backup copies of a VM’s data at a specific point in time

vbm

Veeam Backup Metadata (VBM) file: stores metadata about a VBK file

vib

VMware Installation Bundle (VIB): a package file for installing or upgrading ESXi hosts

vmdk

Virtual Machine Disk (VMDK) file: used in virtual machines like VMware and VirtualBox

vmem

VMware Memory (VMEM) file: a backup of a VM’s RAM content from the host system

vmsd

VMware Snapshot Metadata (VMSD) file: stores metadata about each VM snapshot

vmsn

VMware Snapshot State (VMSN) file: stores the running state of a VM at the time of snapshot

vswp

VMware Swap (VSWP) file: swaps memory pages to the hard drive when a host is low on physical memory

Table 2. File extensions targeted by Mario.

Mario iterates through each of the files in the specified directory path, checking for the targeted extensions. During this iteration process, Mario ignores various entries in the directory, like . (current directory) and .. (parent directory).

The encryptor also ignores files with the following strings anywhere in the filename, even if the filename has a targeted extension:

.marion

.emario

.lmario

.nmario

.mmario

.wmario

This exclusion is likely to avoid double-encrypting files, to avoid the possibility of the files becoming corrupted and unrecoverable.

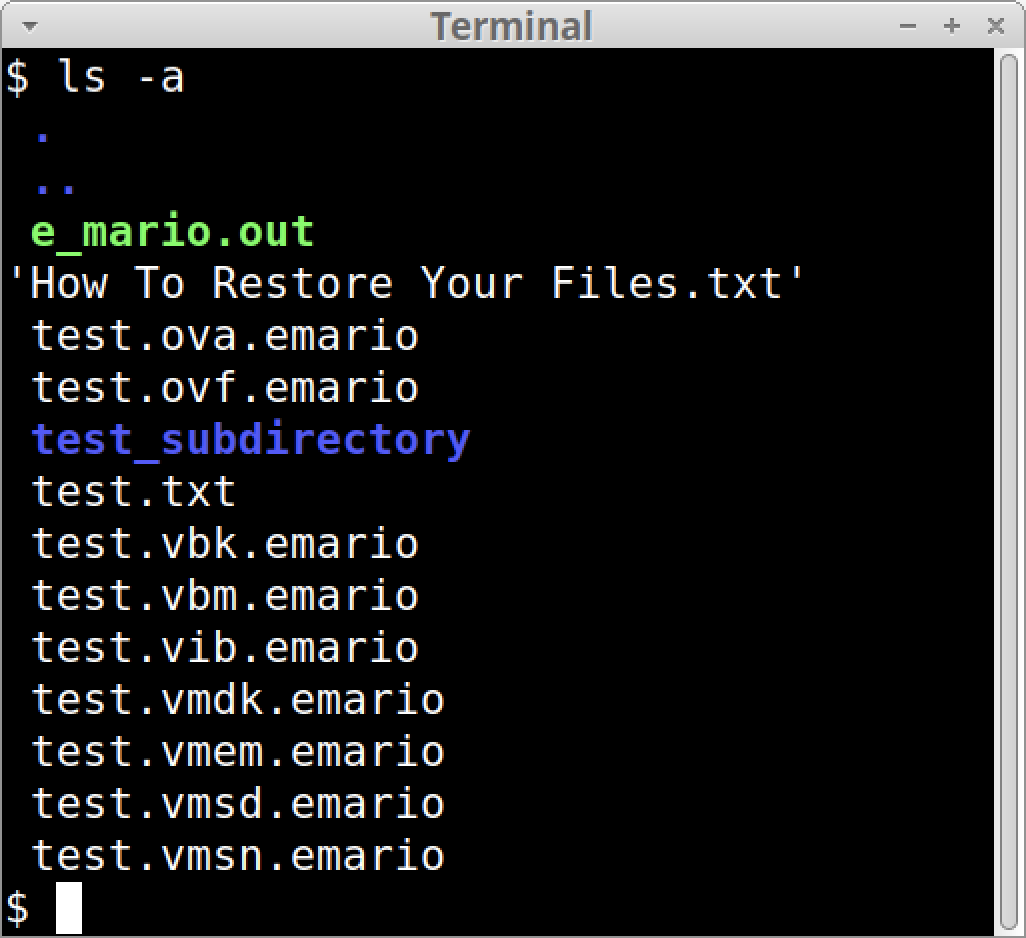

Figure 4 shows the extensions from Table 2 when we tested a Mario sample discovered earlier this year.

Figure 4. Mario sample targeting file extensions associated with virtualization.

Figure 4. Mario sample targeting file extensions associated with virtualization.

Targeting an organization’s virtual infrastructure and backups is a known RansomHouse tactic. Both approaches are intended to inhibit data recovery if a victim does not pay the ransom.

While encrypting targeted files, Mario displays its progress, as Figure 4 above shows. Encrypted files are renamed, appending the existing filename with an extension that includes the string mario. Figure 5 shows an example of .emario as the extension for encrypted files after running a Mario sample.

Figure 5. Listing the directory content reveals encrypted files with the .emario extension.

Figure 5. Listing the directory content reveals encrypted files with the .emario extension.

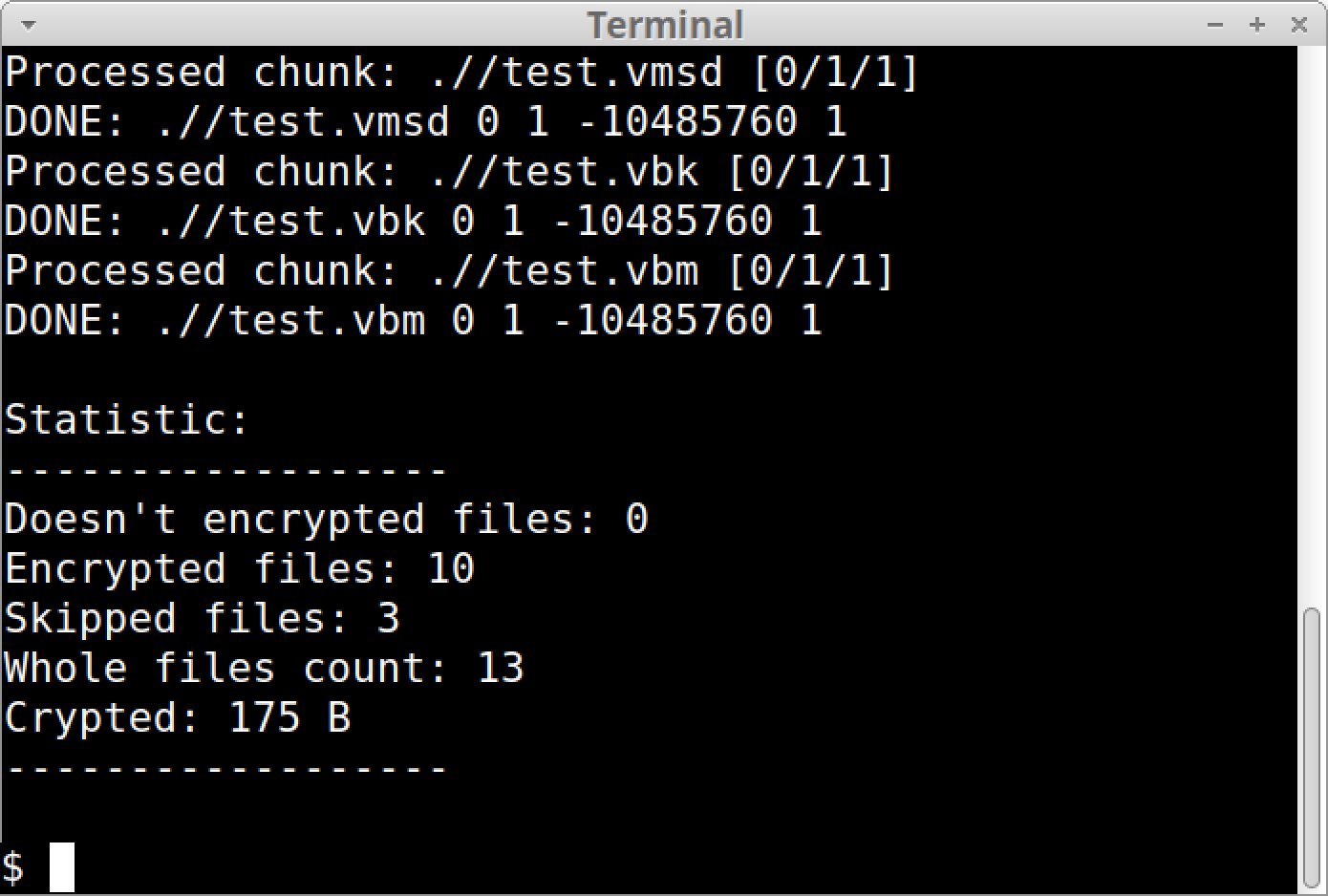

Reporting Statistics

After Mario finishes encrypting targeted files, it displays statistics of the encryption results. These statistics, in order, are:

The number of files that could not be encrypted

The number of files that were encrypted

The number of skipped files

The total file count

The amount of data that was encrypted

Figure 6 shows an example of a statistics report after running a Mario sample.

Figure 6. Example of a Mario sample reporting its encryption statistics.

Figure 6. Example of a Mario sample reporting its encryption statistics.

While all known samples of Mario follow the same execution flow, the process is more complex in recent Mario samples. The next section reviews the differences between the earlier and later Mario samples, revealing an upgrade in Mario’s encryption methods.

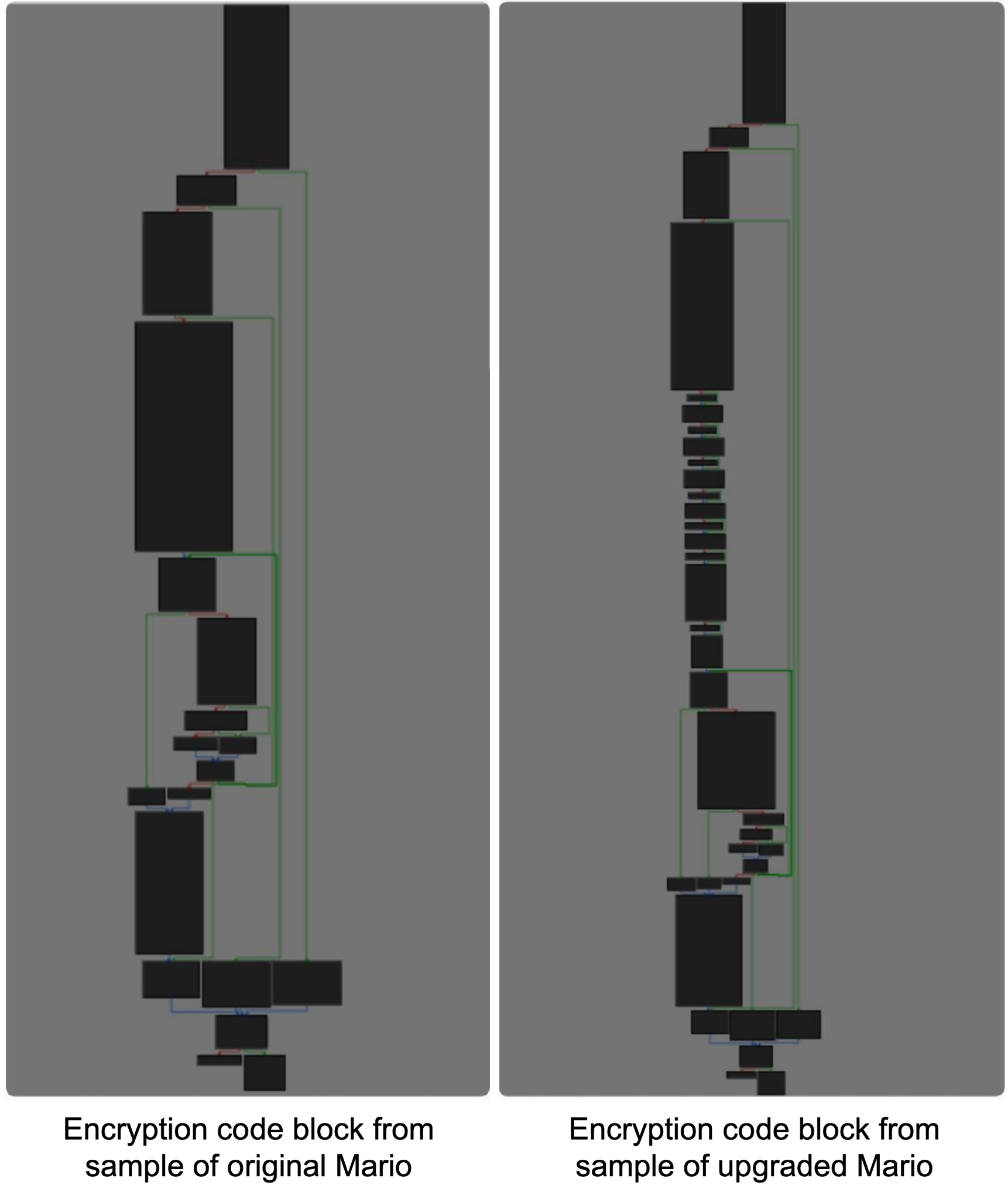

We identified two versions of Mario based on the differences in encryption routines among currently known samples. Comparing these two versions reveals that developers have updated Mario to use a substantially more complex encryption method. We refer to these two versions as:

Original version

Upgraded version

Comparing blocks of disassembled code for the encryption routine, there is a noticeably more complex block of functions in the upgraded version. Figure 7 compares the encryption code blocks for these two versions, showing noticeably more sections in the upgraded version on the right than in the original version on the left.

Figure 7. Comparison of encryption code blocks between the original and upgraded versions of Mario.

Figure 7. Comparison of encryption code blocks between the original and upgraded versions of Mario.

To demonstrate the upgrade in Mario’s encryption, we compare code from samples of the two versions across the following functions:

Encryption

Memory layout and buffer management

File processing

Output format

Improvements in these functions make the upgraded version of Mario significantly more efficient and resilient to analysis than the original version.

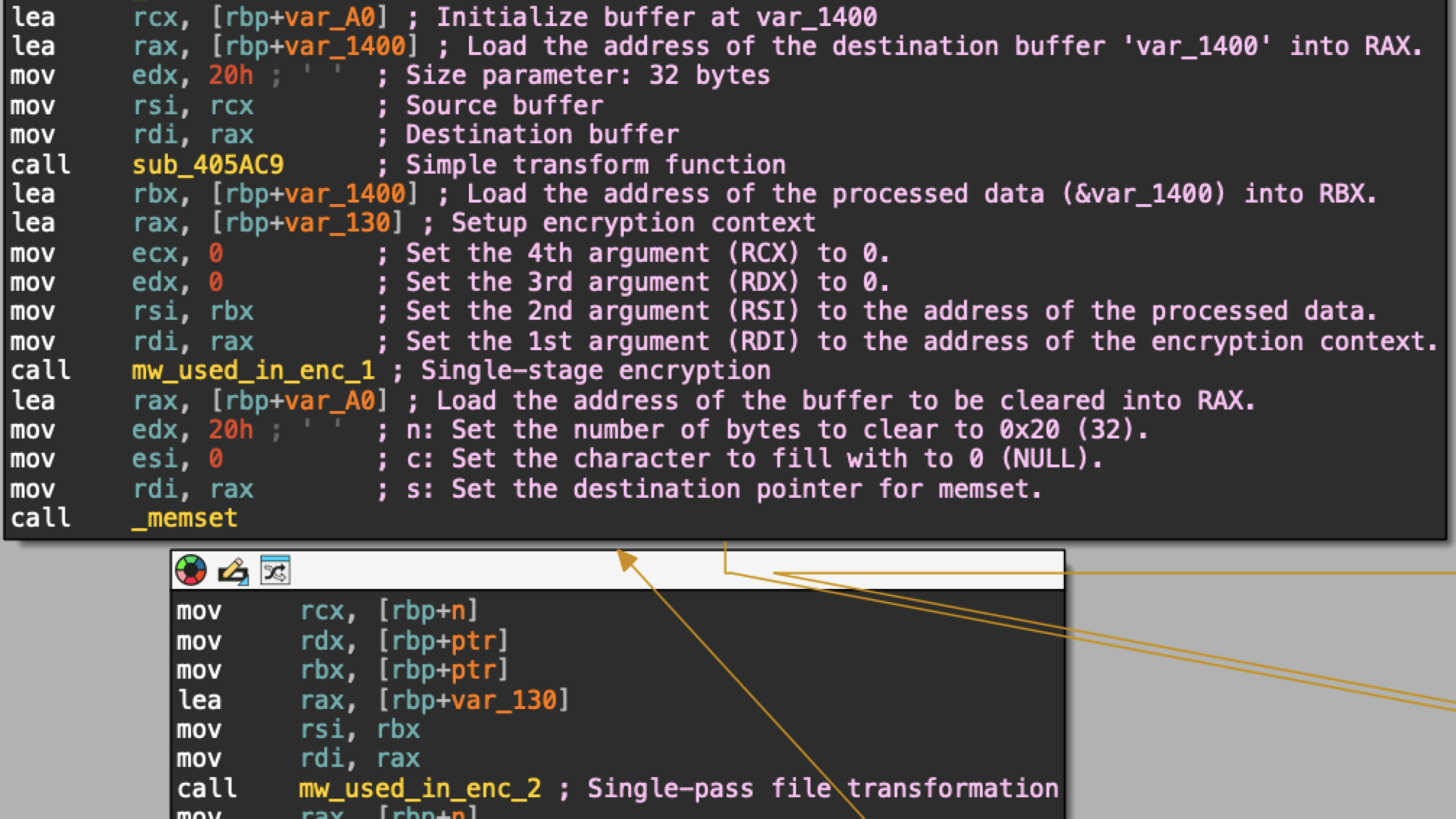

The original version of Mario has a straightforward and basic encryption routine. Figure 8 shows disassembled code from the original version. This code performs a single pass to transform a file’s data from unencrypted to encrypted.

Figure 8. Disassembled code for the original version’s single-pass file transformation.

Figure 8. Disassembled code for the original version’s single-pass file transformation.

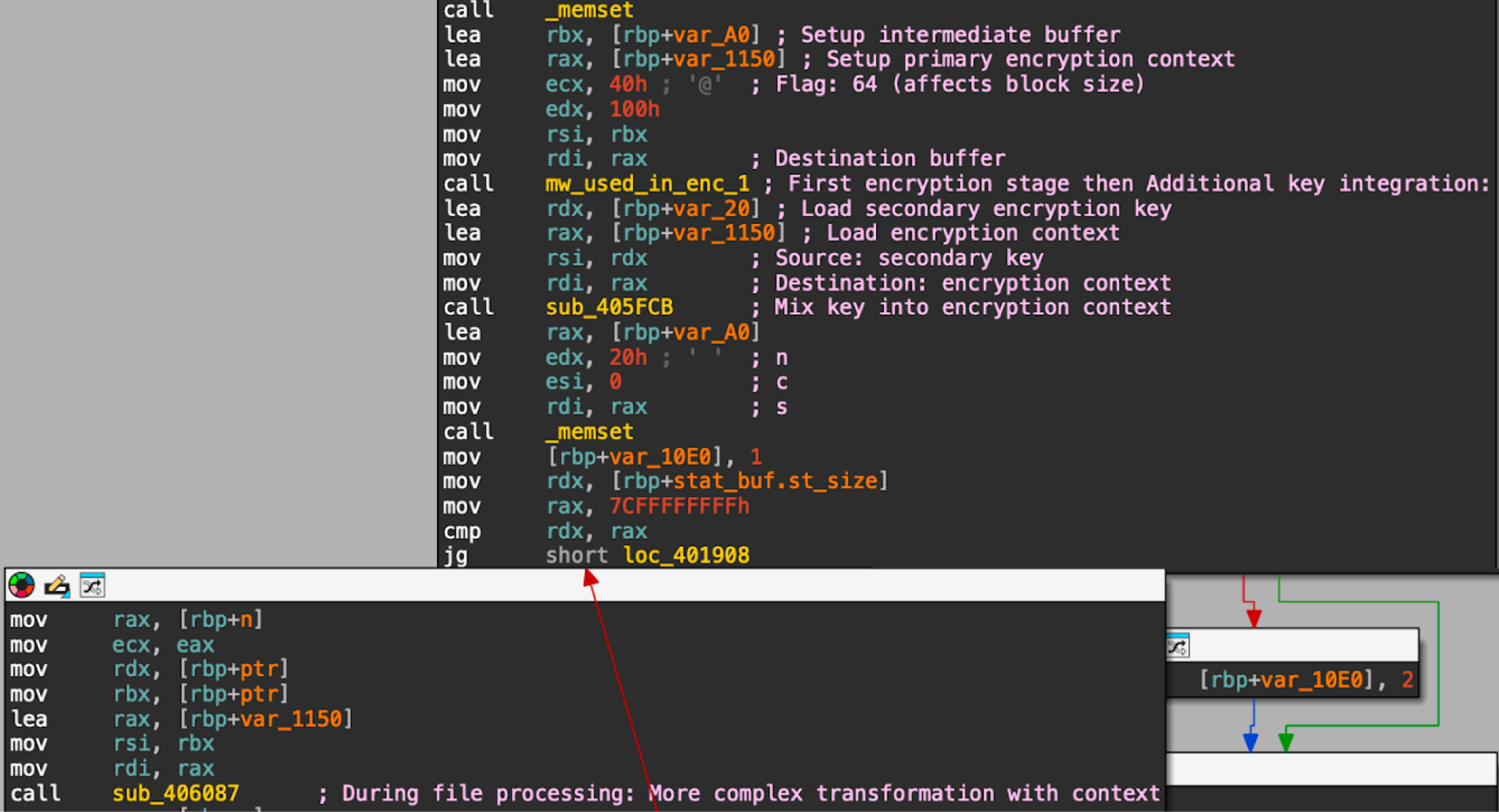

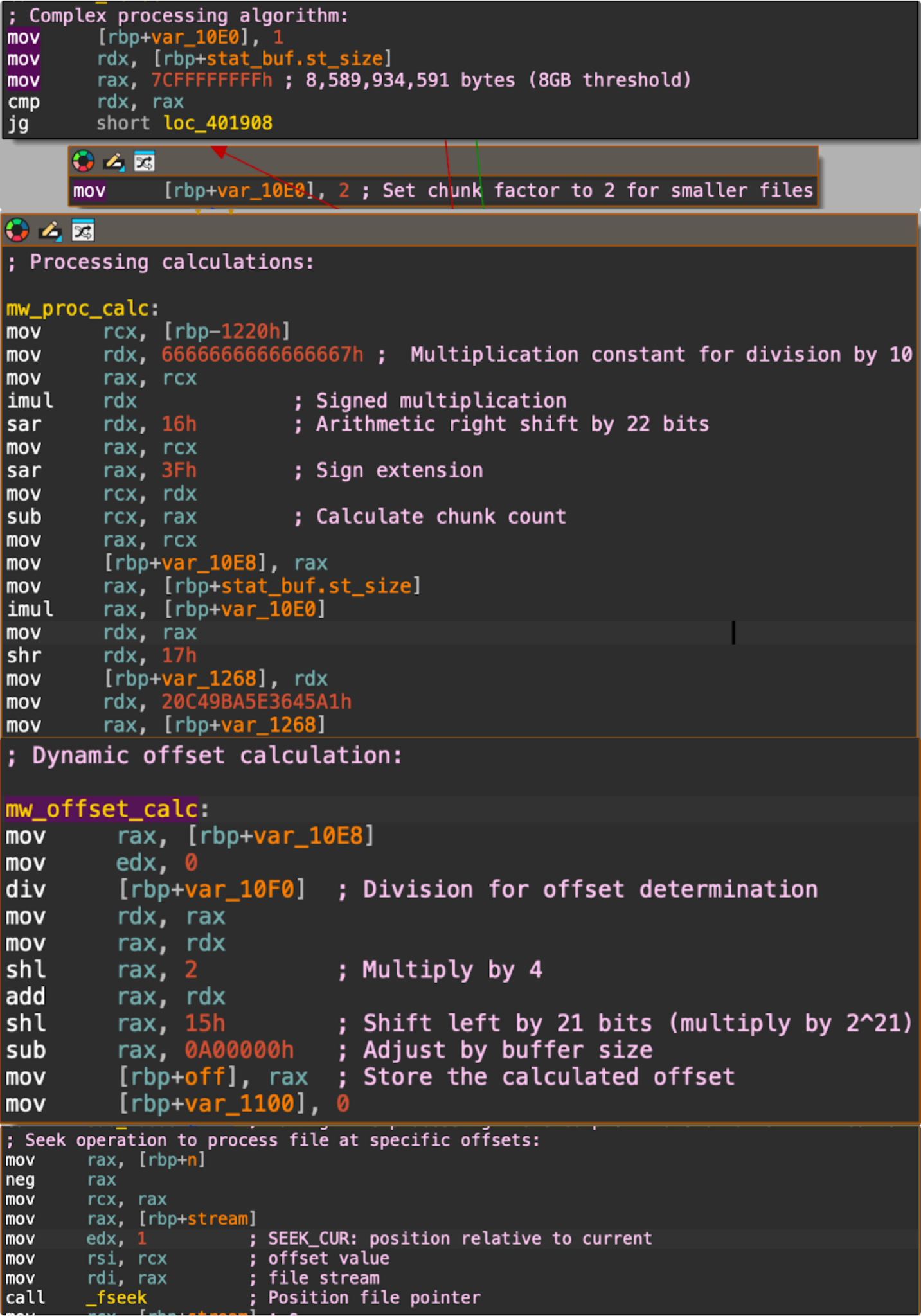

In contrast, the upgraded version of Mario features a two-stage file transformation that includes a secondary encryption key. Figure 9 shows disassembled code from a sample of the upgraded version of Mario, revealing this more complex encryption process.

Figure 9. Disassembled code revealing the upgraded version’s more complex file transformation.

Figure 9. Disassembled code revealing the upgraded version’s more complex file transformation.

The upgraded version’s code reveals a two-factor encryption scheme where the file is encrypted with both a primary key and a secondary key. Data encryption is processed separately for each key. This significantly increases the difficulty of decrypting the data without both keys.

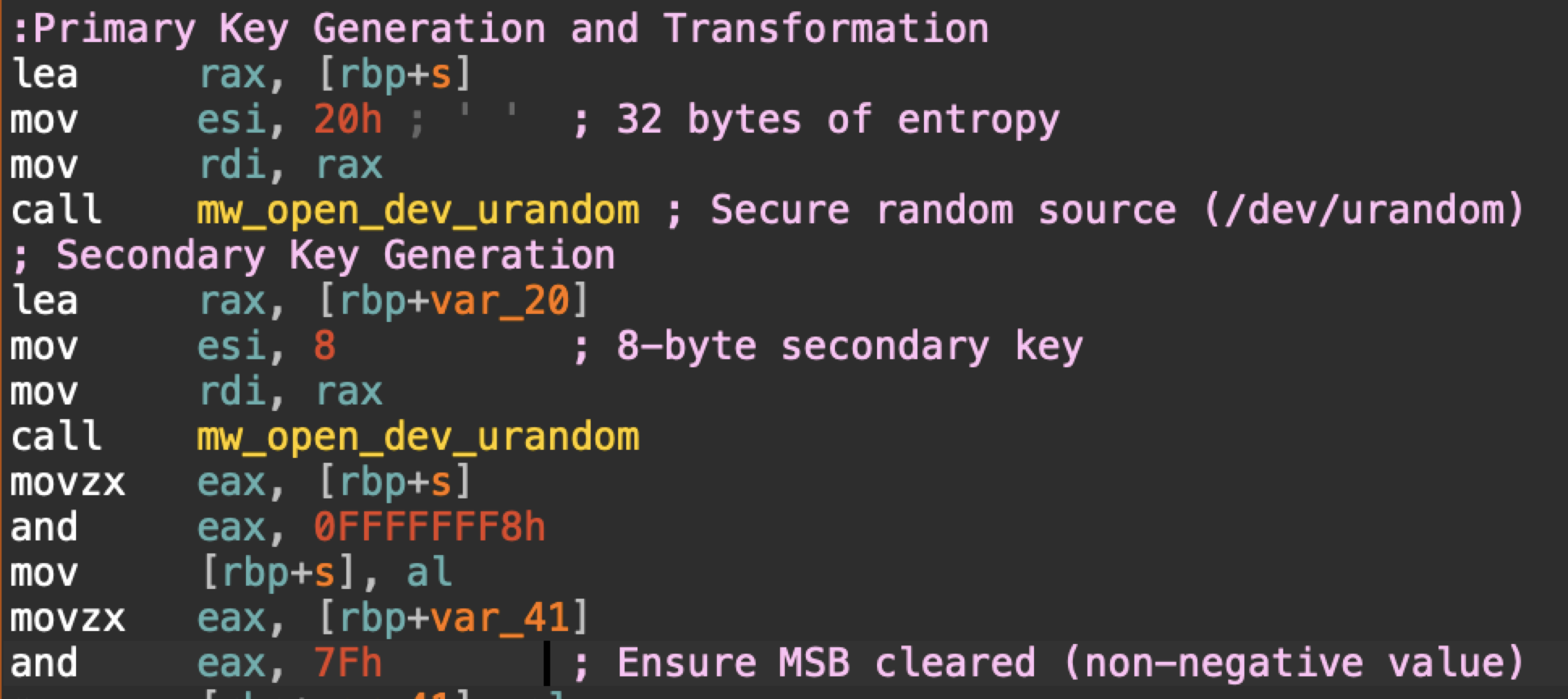

Figure 10 shows that the upgraded version of Mario uses random values to generate a 32-byte primary encryption key and an 8-byte secondary encryption key.

Figure 10. Disassembled code showing key generation used by Mario’s upgraded version.

Figure 10. Disassembled code showing key generation used by Mario’s upgraded version.

These changes represent a significant upgrade in Mario’s encryption.

Memory Layout and Buffer Management

When discussing memory layout and buffer management, we must understand stack frames and buffers. In this case, buffers are portions of the stack frame specified by an offset value.

The original version of Mario uses the following stack frames and buffer values during its encryption process:

Upgraded version stack frame size: 0x1408 bytes

Key buffer offsets: var_1400 (primary), var_130 (transformation)

Chunk size: Fixed at 0xA00000 with no dynamic adjustments

This indicates a relatively straightforward, simple process for transforming files to an encrypted state. In contrast, stack frame and buffer values for the upgraded version of Mario show a more complex structure that is smaller and more efficient:

Upgraded version stack frame size: 0x1268 bytes

Multiple buffer offsets:

var_1150: Primary encryption context

var_A0: Intermediate transformation buffer

var_20: Secondary key storage (8 bytes)

var_40: Header storage for encrypted files

These stack frame and buffer values are used in a process where:

Initial data is read into the primary buffer (ptr)

The data is transformed using the primary key at var_1150

It is further processed with the secondary key at var_20

Final encrypted data includes a header from var_40

The careful organization of these buffers confirms the layered approach of Mario’s upgraded version.

Mario’s original version uses a straightforward approach to file processing. It’s a linear process that encrypts the files as sequential fixed-size segments in a loop. After encrypting each segment, the code checks if the combined size of the processed segments exceeds a specified threshold. Once it passes that threshold, the code jumps from the loop to a different function.

Figure 11 illustrates this linear process in the disassembled code.

Figure 11. Disassembled code showing a linear process for encryption in Mario’s original version.

Figure 11. Disassembled code showing a linear process for encryption in Mario’s original version.

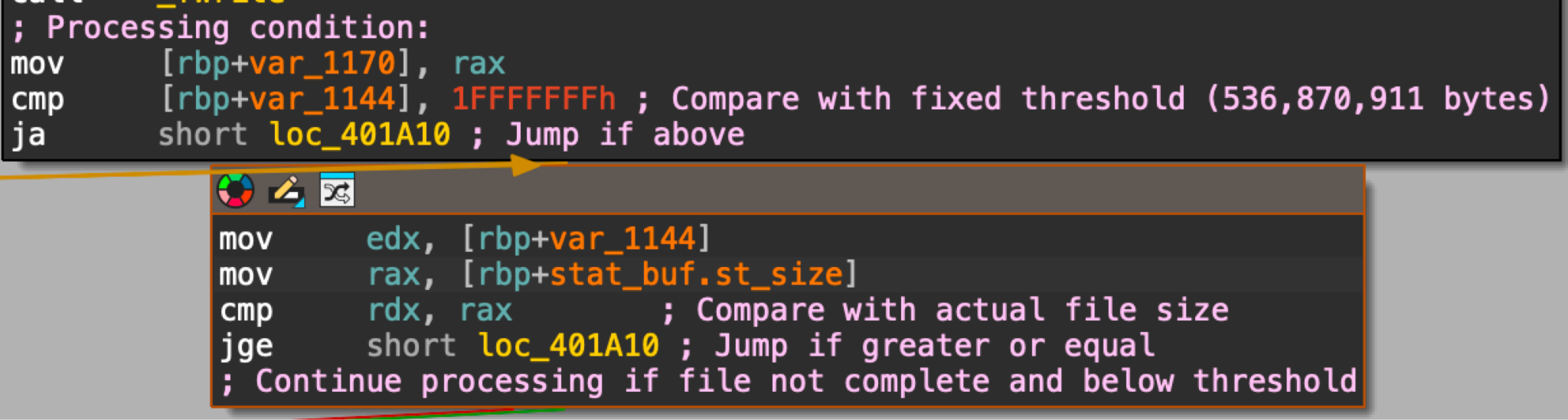

Code in Mario’s upgraded version reveals an encryption method that uses chunk processing with dynamic sizing. Figure 12 shows an example.

Figure 12. Disassembled code showing chunked processing with dynamic for encryption in Mario’s upgraded version.

Figure 12. Disassembled code showing chunked processing with dynamic for encryption in Mario’s upgraded version.

Comparing the processing logic between these two versions, we find significant differences.

Mario’s original version uses a simpler programming loop that processes files in fixed segment lengths up to a threshold of 536,870,911 bytes, as noted in Figure 11. This version simply reports when the encryption is complete without showing any progress.

In comparison, Mario’s upgraded version implements a more robust file processing scheme for encryption that uses:

Variable segment lengths, with a size threshold of 8 GB

Calculations to determine chunk size and offsets

A sparse encryption technique where it encrypts only certain blocks of a file at specific offsets

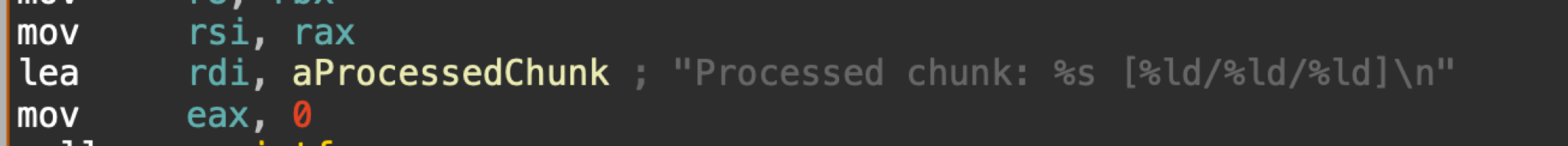

In addition, the upgraded version of Mario displays the progress of encrypting chunks of each file, as noted below in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Disassembled code in the upgraded version of Mario to display the progress of chunk processing.

Figure 13. Disassembled code in the upgraded version of Mario to display the progress of chunk processing.

The chunked processing of Mario’s upgraded version makes static analysis more difficult because:

It processes files non-linearly

It uses complex mathematical formulas to determine processing order

It employs different strategies based on file size

In addition to displaying the processed chunks of files when encrypting them, Mario’s upgraded version also provides a more detailed summary when the encryption of each file is finished.

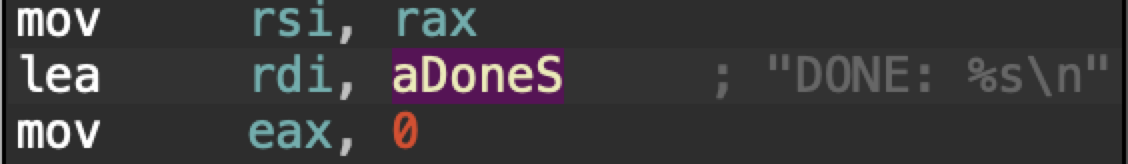

As previously stated, the original version simply reports that the encryption of a file is finished. Figure 14 shows this in the disassembled code.

Figure 14. Code from the original version of Mario to report when a file is finished processing.

Figure 14. Code from the original version of Mario to report when a file is finished processing.

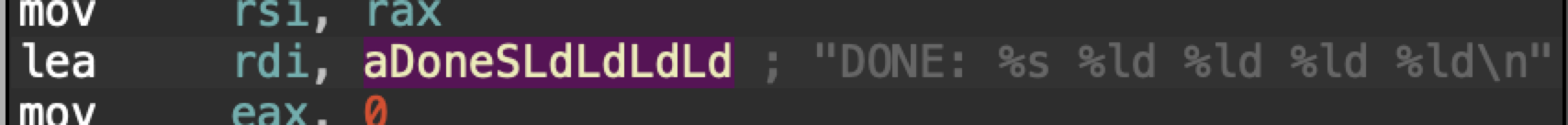

Mario’s upgraded version includes more information when each file is finished processing, as Figure 15 below shows in the disassembled code.

Figure 15. Code from the upgraded version of Mario to report when a file is finished processing.

Figure 15. Code from the upgraded version of Mario to report when a file is finished processing.

Ultimately, the core functionality of these two Mario samples (the original version and the upgraded version) remains the same. Both samples encrypt files and rename them by adding .emario extension. But the upgraded version implements a more complex and potentially more secure encryption methodology with selective file processing.

The upgrade in encryption used by RansomHouse RaaS, going from a simple linear model to a more complex multi-layered approach, signals a concerning trajectory in ransomware development. This demonstrates how threat actors are updating their techniques to enhance effectiveness.

This upgrade is built on several key technical improvements:

A two-factor encryption scheme that significantly increases the difficulty of decryption without both keys

Chunked file processing with dynamic sizing instead of a simpler method

The new file processing makes static analysis and reverse engineering more challenging

Threat actors could view this as a useful path for future ransomware variants. As other ransomware groups adopt these more sophisticated methods, the ransomware threat landscape will become more resilient to security controls. This upgrade underscores the need to adopt more dynamic, adaptive strategies capable of countering the next generation of complex and evasive threats.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed above through the following products:

The Advanced WildFire machine-learning models and analysis techniques have been reviewed and updated in light of the indicators shared in this research.

Cortex Xpanse and the ASM add-on for XSIAM provide detection of VMware ESXi infrastructure exposed to the public internet via “VMware ESXi” and “Insecure VMware ESXi” attack surface rules. In addition to these, there is also a post-compromise detection attack surface rule for “ESXiArgs Ransomware Infection.” This can detect ransom notes injected by malicious actors, as well as other indicators of ransomware infection impacting internet-exposed ESXi servers.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

North America: Toll Free: +1 (866) 486-4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

UK: +44.20.3743.3660

Europe and Middle East: +31.20.299.3130

Asia: +65.6983.8730

Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Australia: +61.2.4062.7950

India: 000 800 050 45107

South Korea: +82.080.467.8774

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

SHA256 hash: 0fe7fcc66726f8f2daed29b807d1da3c531ec004925625855f8889950d0d24d8

File description: Sample of the upgraded version of Mario

SHA256 hash: d36afcfe1ae2c3e6669878e6f9310a04fb6c8af525d17c4ffa8b510459d7dd4d

File description: Sample of the original version of Mario

SHA256 hash: 26b3c1269064ba1bf2bfdcf2d3d069e939f0e54fc4189e5a5263a49e17872f2a

File description: MrAgent sample

SHA256 hash: 8189c708706eb7302d7598aeee8cd6bdb048bf1a6dbe29c59e50f0a39fd53973

File description: MrAgent sample