The scenes of unhinged violence and looting on Dublin’s O’Connell St less than two years ago are still fresh in people’s memories.

The task of identifying those involved in the rioting and criminality on November 23, 2023, has proved to be a colossal undertaking — one largely done manually.

He had done so twice before after building up a relationship with them both over the course of a year.

However, unknown to the girl’s mum, Cheneler was a registered sex offender.

Under the conditions of his court order, he was prohibited from being alone with a child under the age of 14.

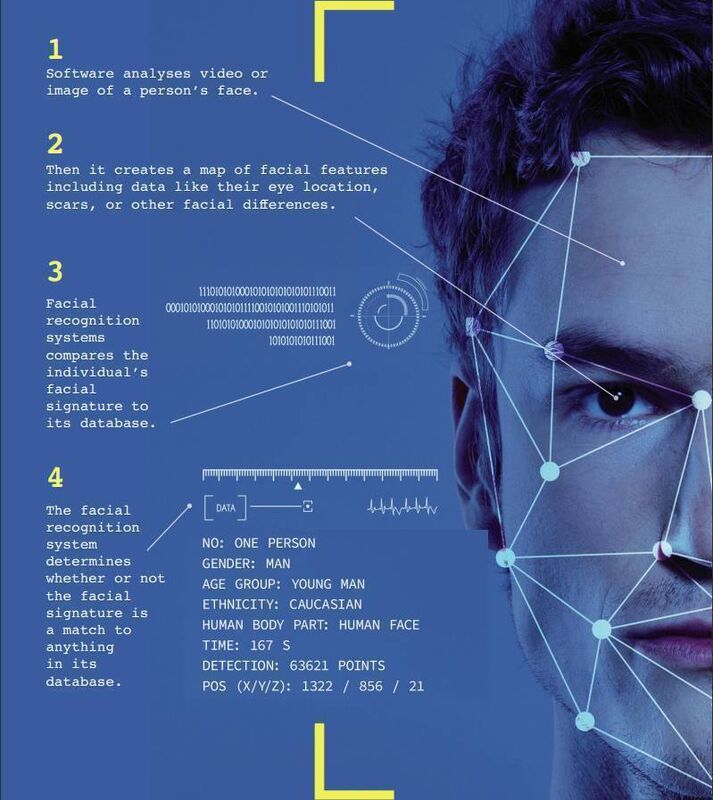

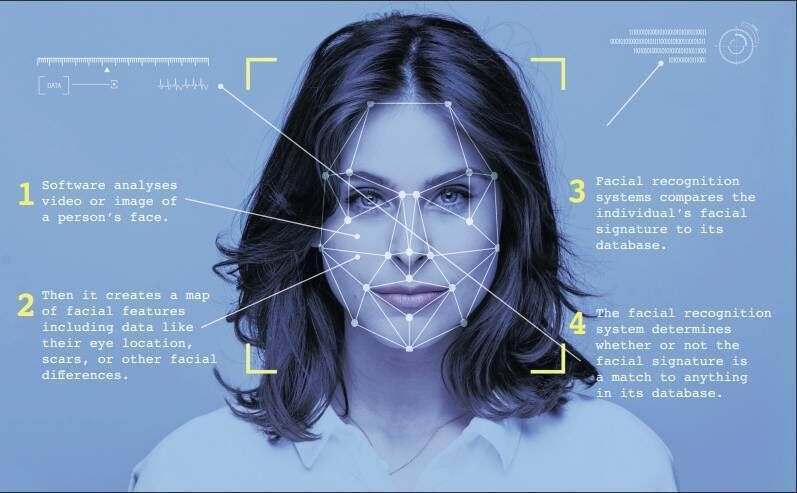

Cheneler happened to pass a live facial recognition (LFR) camera, which captures faces of people walking by and compares them against a database of people on a watchlist.

This includes offenders who have conditions they must adhere to.

Once a match is detected, the system generates an alert which, in this case, was reviewed by an officer. They moved to intervene. They found Cheneler and the girl.

The Met’s lead on LFR said that, without the technology, Cheneler could have had the opportunity to cause further harm.

The following month, Shaun Thompson was outside the London Bridge tube station when police exited a van and told him he was a “wanted man”.

Perplexed, he asked what he was wanted for. He said the police responded: “That’s what we’re here to find out.” Mr Thompson, aged 39 and black, said the officers asked could they take his fingerprints, but he refused.

He said they held him for up to 30 minutes, and he was only let go when he showed them a photo on his passport.

Mr Thompson had just finished a shift in Croydon with community group Street Fathers, which aims to protect young people from knife crime.

He is now bringing a legal challenge based on live facial recognition technology wrongly identifying him as a suspect.

Rights group Big Brother is taking the court challenge with Mr Thompson, saying it is the first time a misidentification case has come before the High Court.

Mr Thompson described the technology as “stop-and-search on steroids”, and said his experience of being stopped and searched had been “intimidating” and “aggressive”.

The London Met Police said it could not comment as proceedings were ongoing, but said its use of LFR was lawful. It said that LFR had led to 457 arrests, with seven false alerts, so far in 2025.

Facial recognition technology is an “intrusive, unreliable, and dangerous” form of surveillance, according to the Irish Council for Civil Liberties.

In a statement to the Irish Examiner, the rights body said risks include the misidentification of individuals as suspects of crime.

It also said there is “inherent biases” in the data sets used to train FRT algorithms, which meant that women and ethnic minorities are at a “significantly higher risk” of being wrongly identified.

It has called on Garda HQ and the Department of Justice to “urgently clarify” what facial image reference databases will be used, along with addressing accuracy and discriminatory concerns of FRT.

The council is concerned by the possibility of gardaí using FRT to monitor people attending a protest or public assembly. It said this would have a “chilling effect” on citizens taking part in protests.

Darragh Murray, a senior lecturer at Queen Mary University of London, penned an academic article for The Modern Law Review which examined FRT from a “human rights law perspective” in 2023.

He also highlighted this chilling effect, which would give rise to “compound human rights harms”.

He said this would affect the “rights of privacy, expression, and assembly”, but also interfere with “the societal processes by which individuals develop their identity and engage politically”.

The Artificial Intelligence Advisory Council told the Government in June 2024 that, while FRT had the potential to speed up investigations and the apprehension of offenders and finding missing persons, these benefits “must be balanced” against the impact on rights.

It urged that “satisfactory independent evaluations” be conducted before deploying FRT.

It said FRT must comply with the EU AI Act, including a fundamental rights impact assessment before procurement. There must also be a complaints procedure as well as periodic independent auditing.

The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission said it considered FRT “a serious interference with individual rights”. However, it added that it recognised a need for An Garda Síochána to “transform its digital technologies” in order to support a modern police service.

It said respect for human rights is an essential part of democracy and the rule of law, adding that “an appropriate balance must be struck between competing rights”.