Scientists have detected hundreds of earthquakes originating from Antarctica’s ‘Doomsday Glacier’, sparking fears of collapse.

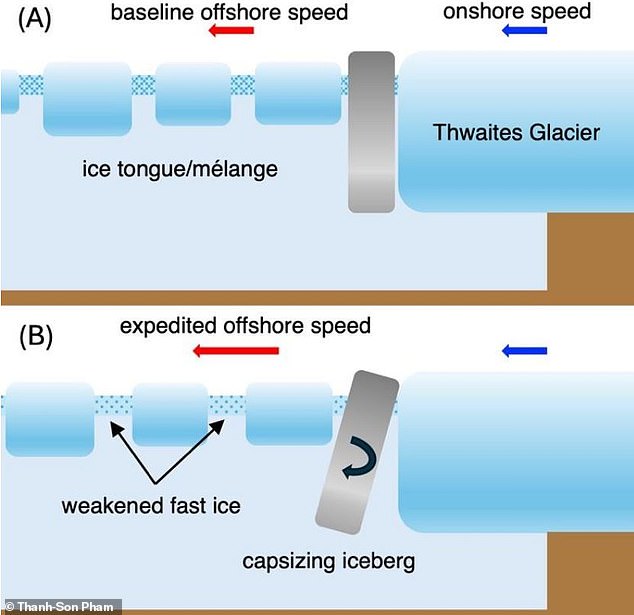

Glacial earthquakes are generated when huge chunks of ice collapse into the sea, crashing into their ‘mother’ glacier as they flip over in the water.

Until now, very few of these worrying tremors have been detected in the Antarctic.

However, in a new paper, an Australian researcher has found over 360 previously unknown earthquakes on the continent.

The vast majority of these seismic events were located at the ocean edge of the Doomsday Glacier, officially known as Thwaites Glacier.

This slow-moving river of ice is roughly the size of the UK and contains enough fresh water to cause irreversible sea level changes should it melt.

Scientists are becoming increasingly concerned that human-caused climate change is putting this critical glacier at risk of total collapse.

The author of the paper, Dr Than-Son Pham, of the Australian National University, wrote in The Conversation: ‘If it were to collapse completely it would raise global sea levels by three metres, and it also has the potential to fall apart rapidly.’

A scientist has detected hundreds of earthquakes originating from Antarctica’s Doomsday Glacier, sparking fears of collapse

The Thwaites Glacier, otherwise known as the Doomsday Glacier, is a slow-moving river of ice as large as the United Kingdom. If it collapsed, it could irreversibly change global sea levels

Although they are still considered earthquakes, glacial earthquakes are very different to the tremors produced by volcanoes and tectonic movement.

Most importantly, they do not produce any ‘high frequency’ seismic waves, which makes them extremely difficult for most earthquake detectors to pick up.

In fact, glacial earthquakes are so elusive that they were only discovered for the first time in 2003.

Until now, the vast majority of glacial earthquakes have been found in Greenland, where the vast Greenland Ice Sheet is crumbling into the ocean.

While their intensity varies, the largest are comparable to the shockwaves produced by North Korea’s recent nuclear weapons tests.

However, even though Antarctica is the largest ice sheet on Earth, scientists have struggled to find direct evidence of tremors caused by collapsing glaciers.

Dr Pham says: ‘Most previous attempts to detect Antarctic glacial earthquakes used the worldwide network of seismic detectors.

‘However, if Antarctic glacial earthquakes are of much lower magnitude than those in Greenland, the global network may not detect them.’

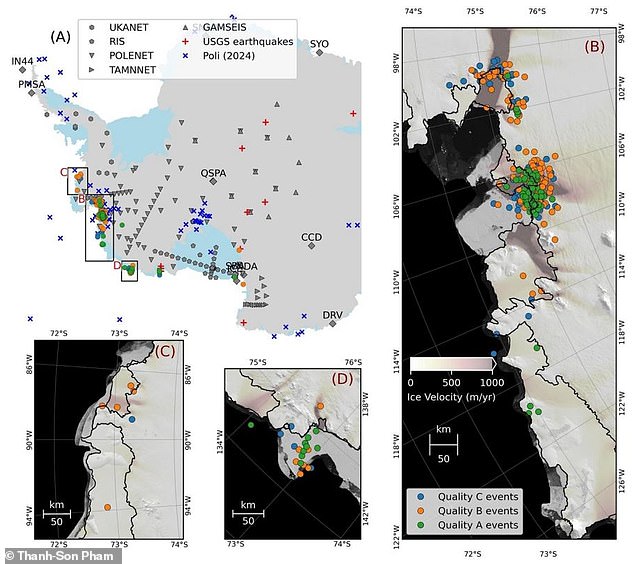

Using seismic stations located in Antarctica, a researcher detected over 360 glacial earthquakes. Two-thirds of these were located in the ocean-facing edge of the Thwaites Glacier (pictured)

Glacial earthquakes occur when tall, thin icebergs break off a glacier. As these glaciers capsize, they smash into their ‘mother’ glacier and produce seismic waves as powerful as those from a nuclear explosion

In this new study, soon to be published in Geophysical Research Letters, Dr Pham used seismic detectors located in Antarctica’s research stations to look for smaller tremors.

Using an automatic detection algorithm, he combed through seismic data collected between 2010 and 2023, turning up 368 earthquakes which were largely unrecorded.

About two-thirds of the events, 245 out of 362, were located near the marine end of Thwaites, while the remaining third were located in the Pine Island Glacier.

Together, these two glaciers have been the largest sources of sea level rise from Antarctica over recent years.

However, unlike glacial earthquakes in Greenland, these tremors weren’t associated with seasonal changes in air temperature.

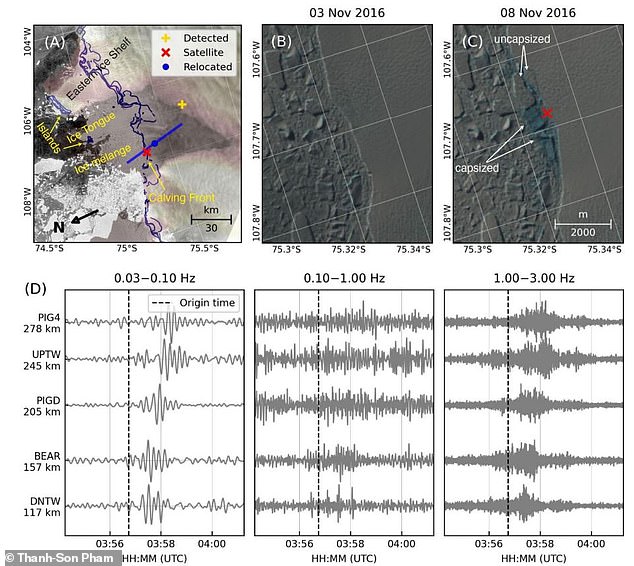

Instead, the most active period of earthquakes occurred between 2018 and 2002 when the glacier’s flow towards the sea was accelerating.

This sudden speed-up could have been caused by ocean conditions, but scientists are still not entirely sure why this occurred.

This is concerning because Thwaites has the potential to significantly increase global sea levels.

The researchers say these tremors (bottom) were more frequent during a period starting in 2016 (top), in which the glacier started rapidly moving towards the sea

Your browser does not support iframes.

Since the 1980s, scientists have called the Thwaites and Pine Island Glaciers the ‘weak underbelly’ of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Due to their wide sea-facing edges, they are particularly vulnerable to the ocean warming effects of human-caused climate change.

And, if they do eventually collapse, the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet could rapidly follow.

This would increase sea levels by about three metres (10 ft), causing widespread flooding around the world and plunging some island nations underwater.

The resulting chaos could destroy cities all over the world, displacing millions of people and forcing a vast number of climate refugees to emigrate to drier inland regions.

Recent studies suggest that sea level rises of just 1.6 feet (0.5 metres) would flood three million buildings in the global south alone.

Dr Pham says: ‘The detection of glacial earthquakes associated with iceberg calving at Thwaites Glacier could help answer several important research questions.

‘These include a fundamental question about the potential instability of the Thwaites Glacier due to the interaction of the ocean, ice and solid ground near where it meets the sea.’

GLACIERS AND ICE SHEETS MELTING WOULD HAVE A ‘DRAMATIC IMPACT’ ON GLOBAL SEA LEVELS

Global sea levels could rise as much as 10ft (3 metres) if the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica collapses.

Sea level rises threaten cities from Shanghai to London, to low-lying swathes of Florida or Bangladesh, and to entire nations such as the Maldives.

In the UK, for instance, a rise of 6.7ft (2 metres) or more may cause areas such as Hull, Peterborough, Portsmouth and parts of east London and the Thames Estuary at risk of becoming submerged.

The collapse of the glacier, which could begin with decades, could also submerge major cities such as New York and Sydney.

Parts of New Orleans, Houston and Miami in the south on the US would also be particularly hard hit.

A 2014 study looked by the union of concerned scientists looked at 52 sea level indicators in communities across the US.

It found tidal flooding will dramatically increase in many East and Gulf Coast locations, based on a conservative estimate of predicted sea level increases based on current data.

The results showed that most of these communities will experience a steep increase in the number and severity of tidal flooding events over the coming decades.

By 2030, more than half of the 52 communities studied are projected to experience, on average, at least 24 tidal floods per year in exposed areas, assuming moderate sea level rise projections. Twenty of these communities could see a tripling or more in tidal flooding events.

The mid-Atlantic coast is expected to see some of the greatest increases in flood frequency. Places such as Annapolis, Maryland and Washington, DC can expect more than 150 tidal floods a year, and several locations in New Jersey could see 80 tidal floods or more.

In the UK, a two metre (6.5 ft) rise by 2040 would see large parts of Kent almost completely submerged, according to the results of a paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science in November 2016.

Areas on the south coast like Portsmouth, as well as Cambridge and Peterborough would also be heavily affected.

Cities and towns around the Humber estuary, such as Hull, Scunthorpe and Grimsby would also experience intense flooding.