Deadline’s Read the Screenplay series spotlighting the scripts behind the awards season’s most talked-about movies, continues with Jafar Panahi’s Neon film It Was Just an Accident, a deeply felt moral thriller and a road-trip revenge story that won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. The film, which made the Oscar shortlist repping France for Best International Feature, combines high-stakes tension with unexpected flurries of humor.

Panahi is the only director to have won the top prize at the trifecta of top film festivals — Cannes, Berlin (Golden Bear) and Venice (Golden Lion). Produced and completed in France in co-production with Les Films Pelléas, It Was Just an Accident marks his triumphant return to pure narrative fiction and his first film in years in which he himself does not appear. The cast is led by Vahid Mobasseri, with Ebrahim Azizi as Eghbal, the sole professional actor in the film.

The pic has had a strong showing on the awards circuit since hitting theaters in September, scoring three wins at the Gotham Awards for Best International Feature, Best Director and Best Screenplay, and four Golden Globes noms for Best Film – Drama, International Film, Director and Screenplay. The script also picked up a Best Screenplay win from the Los Angeles Film Critics, and the film was recognized with a Special Award from AFI.

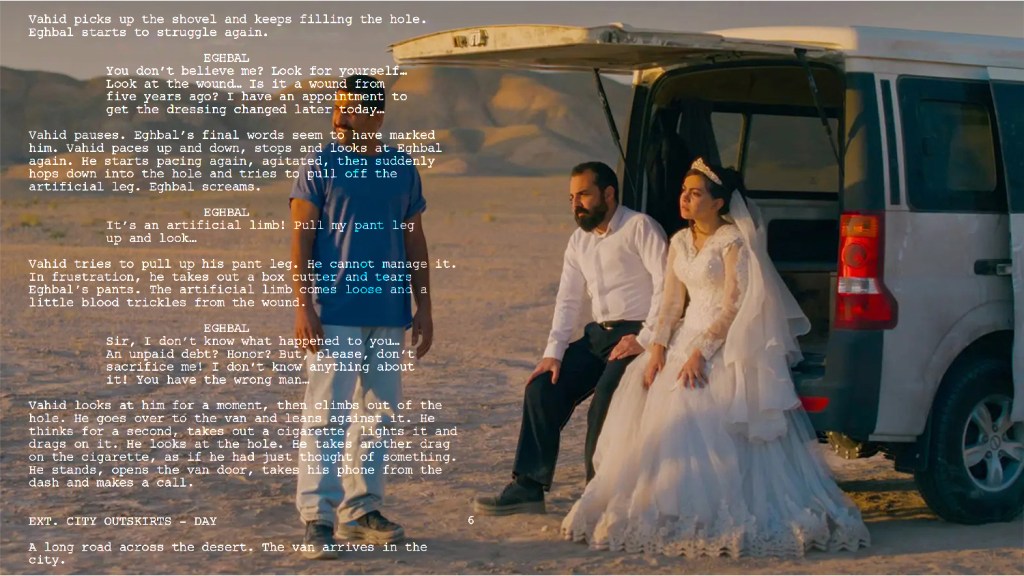

The narrative begins when Vahid, an unassuming mechanic and former Iranian political prisoner, has a chance encounter with Eghbal, a man he strongly suspects to be his sadistic jailhouse captor. Panicked, Vahid gathers several former prisoners, all abused by the same captor, to try and confirm Eghbal’s identity. The story takes off in a rickety van as this diverse and bickering group drives around Tehran with the captive, unconscious Eghbal, forcing them to confront how far they should take matters into their own hands with their presumed tormentor.

This setup is the foundation for the dilemma. The characters all suspect Eghbal is “Peg Leg,” the captor who blindfolded and terrorized them, but none has ever seen his face until now, slyly putting the audience in the same position of moral doubt and unresolved fury. The complications mount when the ex-prisoners encounter Eghbal’s vulnerable family, specifically his pregnant wife and young daughter, triggering a development that forges unexpected connections and pushes Panahi’s empathetic instincts to a peak.

Panahi, who reflects on his past experiences as an Iranian prisoner (he was last in jail in 2023, and was actually sentenced to one year in prison and a two-year travel ban in absentia earlier this month while he was in the U.S. on the awards circuit), creates a work that is at once incisively political yet deeply human. The film is an outcry against an authoritarian regime’s inhumanity, but it goes further to become one of cinema’s most distinctive depictions of tyranny’s greatest countervailing force: the “sheer, beautiful humanness of those who defy it.” The story arose from Panahi’s wish to honor the many Iranian political prisoners he befriended while being imprisoned simply for expressing himself. He has stated, “I don’t make political films, I make human films,” and indeed, his humanity is remarkably enriched in the wake of his own harsh imprisonment.

The film asks crucial questions about humanity and society: How do societies truly move forward after soul-crushing periods of autocracy and state violence? What does true justice look like, and how can vicious cycles of endless payback be averted? The former detainees, who may have lost a sense of their own futures, have not lost the hope that they can help a mother and child in need. Panahi stated the film was made “about right now but for the future,” intended for the children of this generation, with a focus on what comes next whether it be reconciliation, forgiveness or dialogue. The heart-stopping final moment underscores that forgiving is not the same as forgetting, leaving the audience to think about the changes necessary for the future.

Read the screenplay below.