Three days after Christmas, at one of the most scenic locations on the Wild Atlantic Way, a commemoration ceremony will recall the death of a young garda who died in north Clare in the line of duty, exactly 100 years ago, on December 28th, 1925.

The story of the murder of Garda Tom Dowling and subsequent events encapsulates the troubled times when the young Irish State struggled to establish civic order and the rule of law in the aftermath of war. For three years an unarmed police force had striven to pacify and defend communities that continued to suffer from violent crime, often masquerading as patriotism.

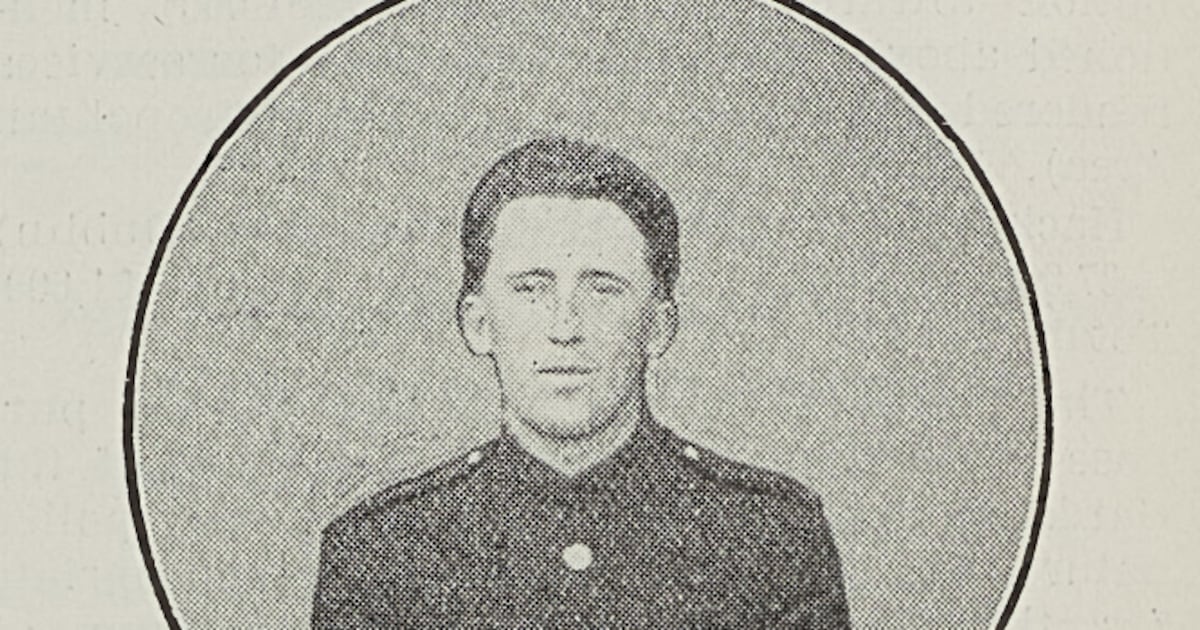

Earlier in the year, the newly formed Special Branch had been deployed around the State. Tough, well-armed “branchmen” quickly started to turn the tide against elements that had ignored Frank Aiken’s 1923 instruction to “dump arms”. But it came too late for 29-year-old Tom Dowling, killed with a shotgun blast while on cycling patrol with his sergeant on the coastal road, near the village of Fanore.

At the place he died, the Burren fields sweep down to beautiful Fanore beach, a popular tourist and camping destination. A Celtic cross, erected by his comrades after his death, marks the location.

It was one of the ironies of the Civil War and its aftermath that many of those who died at the hands of fellow Irishmen had been among the most active in the struggle against the British. Tom Dowling, from Ballyragget, Co Kilkenny, was typical. He had been a leading member of the Kilkenny Brigade IRA. Serving later as a lieutenant in the National Army, he was wounded in action near Clonmel.

Christmas 1925 was to have seen a bonanza for those making poitín – illegal whiskey – across rural Ireland. There had been no effective policing since the neutralising of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). Poitín makers had more or less free rein and product was being transported to the cities, to Britain and even to the United States, where Prohibition was in force. But throughout 1925, the Garda, now reinforced by armed colleagues, had been coming down hard on the illegal distillers.

The illegal distillation of spirits did not merely deprive the cash-strapped Free State of revenue. “Bad” poitín was ruining the health of men, women and children in many places. Minister for Justice Kevin O’Higgins, told the Dáil of schoolchildren “reeling around the road,” out of their senses on poitín.

Gardaí in north Clare were clamping down hard on the poitín makers. And the poitín makers decided – foolishly – to strike back. Three nights after Christmas, an ambush party lay in wait behind the graveyard wall at Fanore, waiting for the regular Garda cycle patrol. As the patrol passed by, they opened fire, killing Tom Dowling instantly. They possibly reloaded and fired again. Four spent shotgun cartridges were found at the scene, which was to prove their undoing.

Predictably, the full force of the State now came down on north Clare. Scores of gardaí and detectives were drafted in. Detective Superintendent James Hunt, who had served in the RIC’s Crime Branch, one of the very few gardaí with experience of crime investigation, was dispatched from headquarters to guide the inquiry.

The gardaí had little doubt about the identities of the attackers, They seized shotguns and other evidence in a series of early-morning house raids. The science of ballistics was in its infancy but Hunt knew that a spent cartridge might be linked to a particular gun by comparing the hammer-mark striations. Weapons and cartridges were sent to Scotland Yard and showed a match.

Three men were charged with Garda Dowling’s murder but were acquitted by an Ennis jury. Feelings in the locality ran high and relations between the gardaí and some of the local people were, understandably, strained as the investigation advanced. Opinions still differ about the tragedy and its outcome.

Clare historian Joe Queally tells the story in detail in his meticulously researched 2021 book Echoes From A Civil War. Tom Dowling was laid to rest in his native Kilkenny with full State honours. Today there is no Garda station in Fanore, the nearest being Ballyvaughan. Supt Hunt lived in retirement in his native Roscommon and died in 1976.

In the summer of 1925, Supt Cornelius (‘Con’) Brady had been appointed to north Clare. The former language teacher, wholly inexperienced in crime, found himself, at the tender age of 23, with responsibility for the investigation of a murder, undoubtedly the work of misguided and foolish young men, but which had to be construed as challenging the authority of the new State.

His son, contributor of this diary, will be among those gathering at Fanore on December 28th to commemorate this tragedy of 100 years ago. Representatives of Garda Dowling’s family will be present as well as people from the locality and gardaí serving and retired from the Clare-Tipperary division.