My first professional contract was scribbled on the back of a notebook.

Midway through the 1998/99 season, I approached the Leinster coach Mike Ruddock to ask about improving it.

I had other offers. One was from Ulster, along with a promise to play me at fullback – my preferred position at the time.

Mike stopped, looked me up and down, and said the terms of the contract would not change. Then he asked two questions that have stayed with me ever since: Did I want to stay and fight for a place, or take what might be perceived as the easier option elsewhere? There might be more money in leaving, he said, but would it ever mean as much as playing for Leinster?

I remembered that conversation when it was confirmed this week that Ciarán Frawley is leaving Leinster to join Connacht next season. I wonder whether we are in danger of losing something that has made playing for each province so unique.

Leinster and Munster’s battle for rugby’s soul

Leinster and Munster’s battle for rugby’s soul

There are examples of players who have moved and thrived. Andrew Conway found success with Munster after leaving Leinster. Tadhg Beirne excelled in Wales with the Scarlets, having been cut loose by Leinster, before returning to Ireland as a Munster player.

Movement between the provinces is not inherently wrong, nor should ambition be discouraged as careers are short and opportunities must be taken.

But we also need to be honest about the motivation. Is the move about playing more regularly, or is it about increasing his chance of wearing the green jersey? If it is the latter, then a difficult question follows: If a player cannot hold down a starting position in their native province, will more game time elsewhere change the national pecking order?

History suggests otherwise. I said it when the former IRFU performance director David Nucifora floated the idea of moving players around the provinces to get more minutes, and I believe it just as strongly now – there is no quick fix to player development.

Each province should be producing enough players of sufficient quality to field a competitive team. Too often, the solution has been to look overseas or shuffle players within the system rather than addressing the root of the problem: Irish rugby sources most of its talent from a very small, very specific socio-economic pool.

Frawley’s move will undoubtedly strengthen Connacht and marginally weaken Leinster. It remains to be seen if increased minutes in his preferred position – outhalf – will see him reach his full potential.

Tadhg Beirne in action for Munster against Leinster. Photograph: Bryan Keane/Inpho

Tadhg Beirne in action for Munster against Leinster. Photograph: Bryan Keane/Inpho

There is ambition in the decision. Frawley, presumably, wants to be a first choice 10, not third string behind Sam Prendergast and Harry Byrne, and with a World Cup on the horizon it should place him in the shop window.

But in a broader context, we need to consider the cumulative effect of players moving from one province to another.

Some of my strongest rugby memories are tied to interprovincial matches. They go back to my final year in school, when I first got a taste of representative rugby. From the outset, it was drilled into us that pulling on a Leinster jersey carried an honour and a responsibility. This was something bigger than your school, bigger than you.

The first time I was selected for a Leinster underage side remains a special moment. I had already played three years of senior schools rugby, and while some players were content to represent the school, I wanted more.

One of the initial challenges was learning to park what we had been doing on our school team and adapt to a new environment. We were conditioned to dislike rival players but now we were expected to work together.

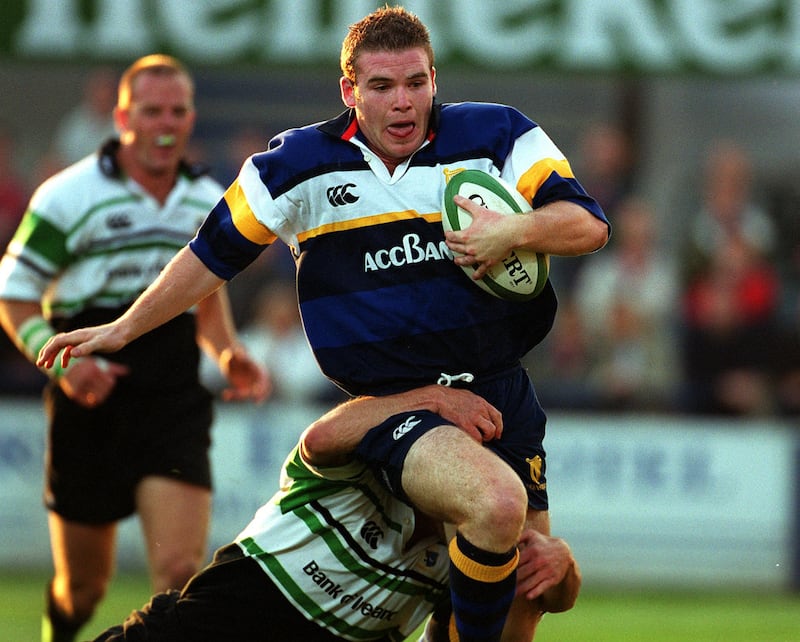

Gordon D’Arcy during an interpro between Leinster and Connacht in September 2000. Photograph: Billy Stickland/Inpho

Gordon D’Arcy during an interpro between Leinster and Connacht in September 2000. Photograph: Billy Stickland/Inpho

The message was clear: each time you were handed the blue jersey, it was special. It gave us a common focus and a shared goal that transcended rivalries.

I signed for Leinster straight out of Clongowes Wood College, and the interpros quickly became the most intense rugby I had ever experienced. It remains so to this day. The old stereotypes proved true – Munster were the hard men, Leinster the skilful ones – as each occasion became an Ireland trial.

There was an edge to the derbies. That fierce competition and dislike of the neighbours has never left me, and last Saturday at Thomond Park showed that this sentiment is shared by current players.

Leo Cullen joked recently about how many Leinster men appeared in a Munster match day 23. It raises a serious question beneath the humour: Are we strengthening one province by weakening another, and does that ultimately raise or lower the overall standard of rugby in Ireland?

My view has always been that it lowers it. Players who are not quite good enough to start for one province become starters elsewhere. That should serve as a warning rather than a solution. It highlights how badly we need a functioning pathway outside the schools system to keep provinces competitive and retain their individual DNA.

We do not have to look far for a cautionary tale. In Wales, financial pressures are bearing down heavily on the regions with at least one team expected to disappear next season. The failure to develop enough players of sufficient quality has contributed directly to the collapse of their national team. That decline did not happen overnight. The pathways eroded first.

Irish rugby has built something valuable through provincial identity, rivalry and player development. Protecting it requires honesty and long-term thinking, not short-term fixes that risk eroding what made the jersey matter in the first place.