As satellite launches surge toward 1.7 million by 2030, astronomers and space companies are turning to multilateralism to mitigate satellite brightness and radio interference and keep astronomy alive.

Last month, President Donald Trump signed an executive order on “American space superiority”, reaffirming US support for the rapid expansion of commercial satellite constellations and framing them as critical infrastructure for national security and economic growth.

The push mirrors moves by the European Union, which signed a €10.6 billion contract for its IRIS² constellation exactly a year ago, while China’s state-backed Guowang network already has over 100 satellites in orbit and plans to deploy 13,000 more in the coming years. The result is a filing frenzy at the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a Geneva-based UN agency that coordinates spectrum and orbital resources. Forecasts now point to as many as 1.7 million non-geostationary satellite launches in low Earth orbit by 2030.

For the commercial space industry, the future of megaconstellations looks bright. For thousands of professional astronomers – and the vastly larger community of amateur stargazers – it’s obscuring efforts to uncover the universe’s secrets.

Mega satellite constellations are becoming both a defence infrastructure and a lifeline for internet access. But they also reflect sunlight into telescope cameras and emit radio signals that leak into frequencies reserved for science. As their numbers grow, the sky is becoming brighter and noisier, threatening optical and radio observation – the two fundamental ways humans study the cosmos.

Satellites and other objects streak across the night sky above the Märkisch-Oderland district in eastern Brandenburg, captured with a 20-second exposure on 2 May 2024. (Keystone/Patrick Pleul/DPA)

Race for solutions enters the UN

With SpaceX’s Starlink holding a multi-billion-dollar near monopoly in low Earth orbit and no enforceable international treaty to protect dark and quiet skies, scientists and skywatchers are up against the clock. International policy moves far more slowly than satellite deployment, and by the time regulations catch up, experts warn, the sky may already be irreversibly altered. In the absence of binding limits, the astronomy community has been working with regulators and operators to develop technical mitigation measures, an approach whose effectiveness depends on coordination across borders.

That dependency has pushed the debate beyond observatories into UN policy forums, with two bodies taking the lead. The ITU, which has protected radio astronomy frequencies for the past 50 years, has been focusing its efforts on interference from non-geostationary satellite systems like Starlink. In parallel, the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (Unoosa) in Vienna has taken on the challenge of tackling satellite brightness. Its Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (Copuos) agreed in 2024 to establish a dedicated agenda item on dark and quiet skies after years of pressure from the scientific community.

“We chose direct engagement with industry, regulatory work at the ITU, policy discussions at Copuos and national level engagement with regulators,” says Federico Di Vruno, spectrum manager at the SKA Observatory and vice-chair of a key ITU working party on radio astronomy. From the industry side, Enrique Allona of the European space company OneWeb sees this split favourably. “The ITU should be the platform for quiet skies…For dark skies, Copuos and its working groups of experts of all backgrounds are where significant advancements can be made,” the engineer says.

Both satellite constellations and astronomical research are lawful uses of outer space under the Outer Space Treaty that governs activities beyond Earth’s atmosphere, yet the 1967 treaty was written at a time when satellite launches were still only in the hundreds and government-run, leaving key questions of interference and accountability unresolved. However, the treaty does require that states act with “due regard” to the interests of others and avoid “harmful interference” – principles that extend to private operators since states bear international responsibility for national space activities.

Whether existing institutions can move fast enough remains an open question. Copuos operates by consensus and moves cautiously. The ITU has binding authority, but only over radio frequencies. Neither has enforcement power when it comes to optical astronomy.

For Olivier Hainaut, an astronomer at the European Southern Observatory based in Munich, multilateralism remains the only realistic option despite its limits. “Space is a global commons, and low Earth orbit affects all countries,” he says. “Creating a new organisation would take a long time, and we would lose precious time.”

Two problems, two sciences

To further complicate matters, the impact of megaconstellations on astronomy is uneven. Radio and optical astronomy face fundamentally different challenges, with effects varying widely from one telescope to another.

In radio astronomy, the threat is more existential. Satellites emit not only intentional signals but also unintended electromagnetic noise from onboard electronics, which can leak into frequencies astronomers use to listen for faint signals from the early universe, emitted billions of years ago. “These effects are currently not addressed by any regulatory framework because the scale of this leakage is unprecedented,” explains Di Vruno.

Built in the remote Murchison region of Western Australia, these antennas are part of SKA-Low, one of the world’s most powerful radio telescopes, operated by the Square Kilometre Array Observatory. (SKAO/Max Alexander)

The issue is now being examined by ITU study groups working on potential solutions ahead of the 2027 World Radiocommunication Conference in Shanghai, such as tighter limits on out-of-band emissions, expanded safeguards for astronomy bands and formal recognition of radio quiet zones, areas granted special protection for radio astronomy under national law. “But satellites with mitigation for radio leakage have not been launched yet,” Di Vruno warns. “We are working with operators who are testing their satellites’ radio effects on the ground.”

In optical astronomy, vulnerability depends heavily on the telescope’s design. Instruments that quickly scan vast areas of the sky are particularly exposed.

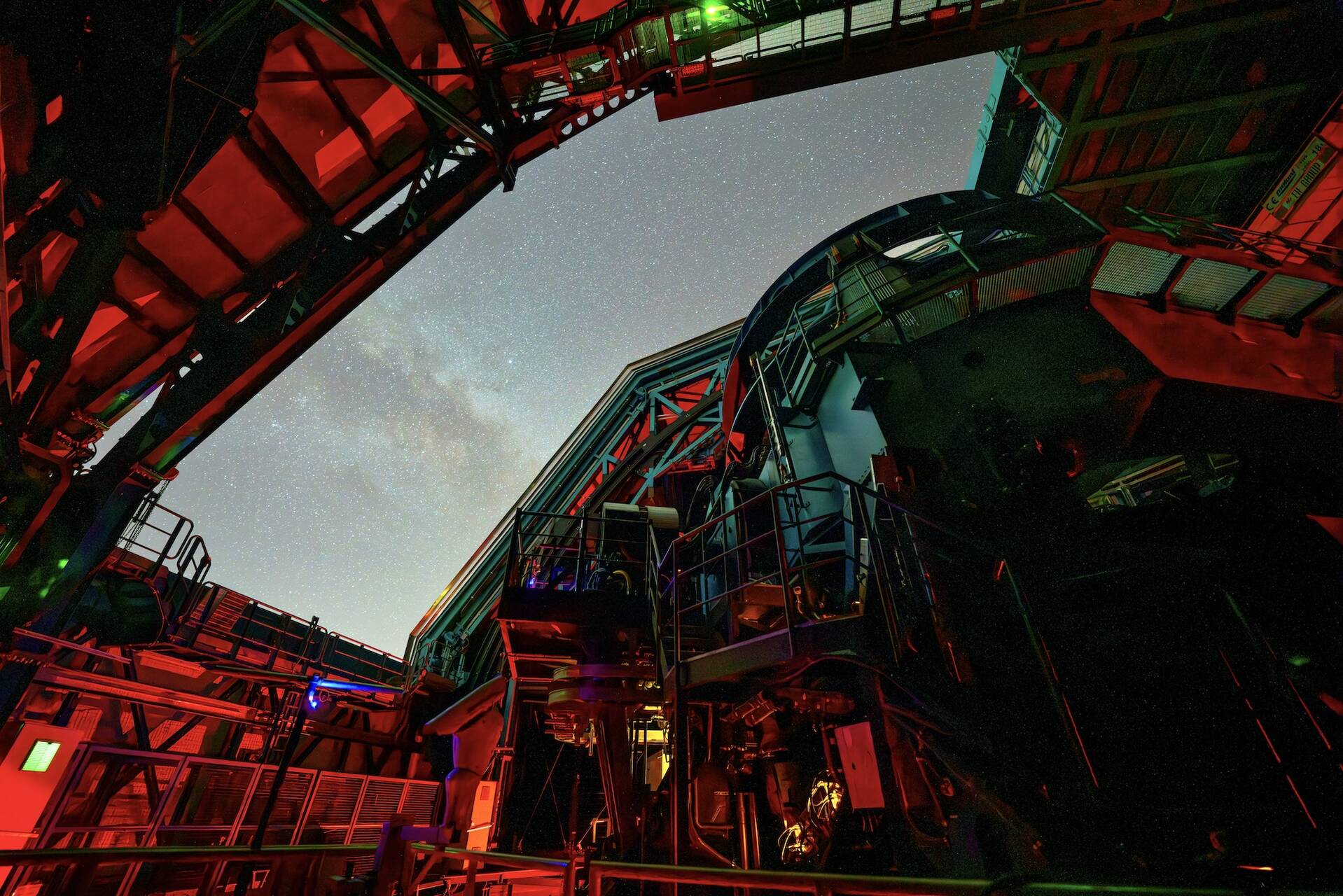

Meredith Rawls, a research scientist working on the recently deployed Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, says the telescope is especially vulnerable. “All the features that make it powerful – its sensitivity and wide field of view – also make it more likely to see satellites,” she says.

The next-generation sky mapping telescope can image the entire southern sky every few nights, detecting up to 10 million changes per night, like asteroids, supernovae and variable stars.

This image shows the Simonyi Survey Telescope taking on-sky observations with a 144-megapixel test camera called the Rubin Commissioning Camera on 24 October 2024. (RubinObs/NSF/DOE/NOIRLab/SLAC/AURA/H. Stockebrand)

After six months of collecting data, satellite streaks can already be seen. Rawls’s team is still assessing whether the trails can be removed without damaging the data.

“It’s not catastrophic,” she says. “Rubin will still do incredible science. It’s just an extra complication we didn’t originally plan for.”

A 2025 study in the online magazine Nature suggests the problem may extend beyond ground-based telescopes, with one third of the images taken by the low-orbit Hubble Space Telescope potentially contaminated if all constellation plans are completed.

Industry takes action

At the ITU’s space sustainability forum in Geneva last October, SpaceX’s lead engineer, David Goldstein, admitted candidly that the company had not fully anticipated Starlink’s impact on astronomy when deployments began in 2019. Since then, major operators say they have tested technical measures to reduce interference, but with mixed results and independent verification still limited.

Amazon’s low Earth orbit programme, Leo, told Geneva Solutions by email that all its satellites use a “custom-made di-electric film and non-reflective coating to reduce brightness”. Meanwhile, French satellite operator Eutelsat’s OneWeb uses fully steerable solar arrays to minimise reflection of its satellites.

SpaceX, which did not respond to Geneva Solutions’ inquiries, presented its solutions at a recent Unoosa event in Vienna. Musk’s company has experimented with darker satellite coatings, deployable flap-like sunshades and mirror-like surfaces to block or reflect sunlight away from Earth.

“The difference is visible even to the naked eye,” says Hainaut, praising the operators’ efforts. “Satellites are much fainter overhead, becoming brighter mainly near the horizon toward the Sun.”

For radio astronomy, operational measures such as steering satellite transmissions away from radio telescope beams offer more promise. Already used in the United States around facilities like the Very Large Array, a major observatory in the southwest of the country, this model could scale globally if backed by regulation.

Astronomers acknowledge greater industry efforts but caution that mitigation remains voluntary, uneven across operators and largely excludes military satellites. “I would say it’s now a mix of genuine effort and marketing claims,” Rawls says.

Hainut further points out that no single mitigation works on its own. “We need mitigation at every level – constellation design, satellite design, operations, observation planning and data processing,” he says.

Crowded skies ahead

Even with these measures in place, the sheer volume of planned satellites raises deeper concerns about whether the sky can sustain current growth trajectories.

“Ten thousand satellites works, 50,000 probably works, 100,000 becomes problematic,” Hainut says. “One million is essentially hopeless.”

Orbital crowding and the risk of cascading collisions that render entire orbital zones unusable will be a “limiting factor before astronomy shuts down”, he says. Di Vruno also points out that observations are becoming more expensive, requiring more telescope time and computational resources to clean contaminated data.

Beyond constellations already in orbit, astronomers are watching two emerging threats with particular alarm.

The first involves satellites designed to reflect sunlight to Earth at night, effectively creating artificial daylight for specific regions. These “sunlight-as-a-service” concepts would require thousands of satellites and, Hainaut warns, “could wipe out several hours of night sky for astronomy”. Not to mention, “major ecological impacts beyond astronomy”.

One California-based company has already filed a license request with the US federal communications commission for a prototype system. Astronomers expressed concerns during the public consultation period, and the FCC has requested additional environmental impact information. The application remains pending.

A second concern is space advertising in the form of giant reflective satellites that could turn the night sky into a billboard visible to the naked eye. Just before the summer, the Russian start-up Avant Space said it had launched what it called the first “space media satellite” capable of rendering logos visible from the ground. Some countries like the US ban “obtrusive space advertising” through federal law, but there is no comprehensive international ban.

A screenshot of a promotional video published on Avant Space’s website.

Only a couple of months earlier, the International Astronomical Union had already raised the alarm at a Copuos meeting, warning that the technology amounted to the “ultimate light trespass” and urging national delegations to consider a ban.