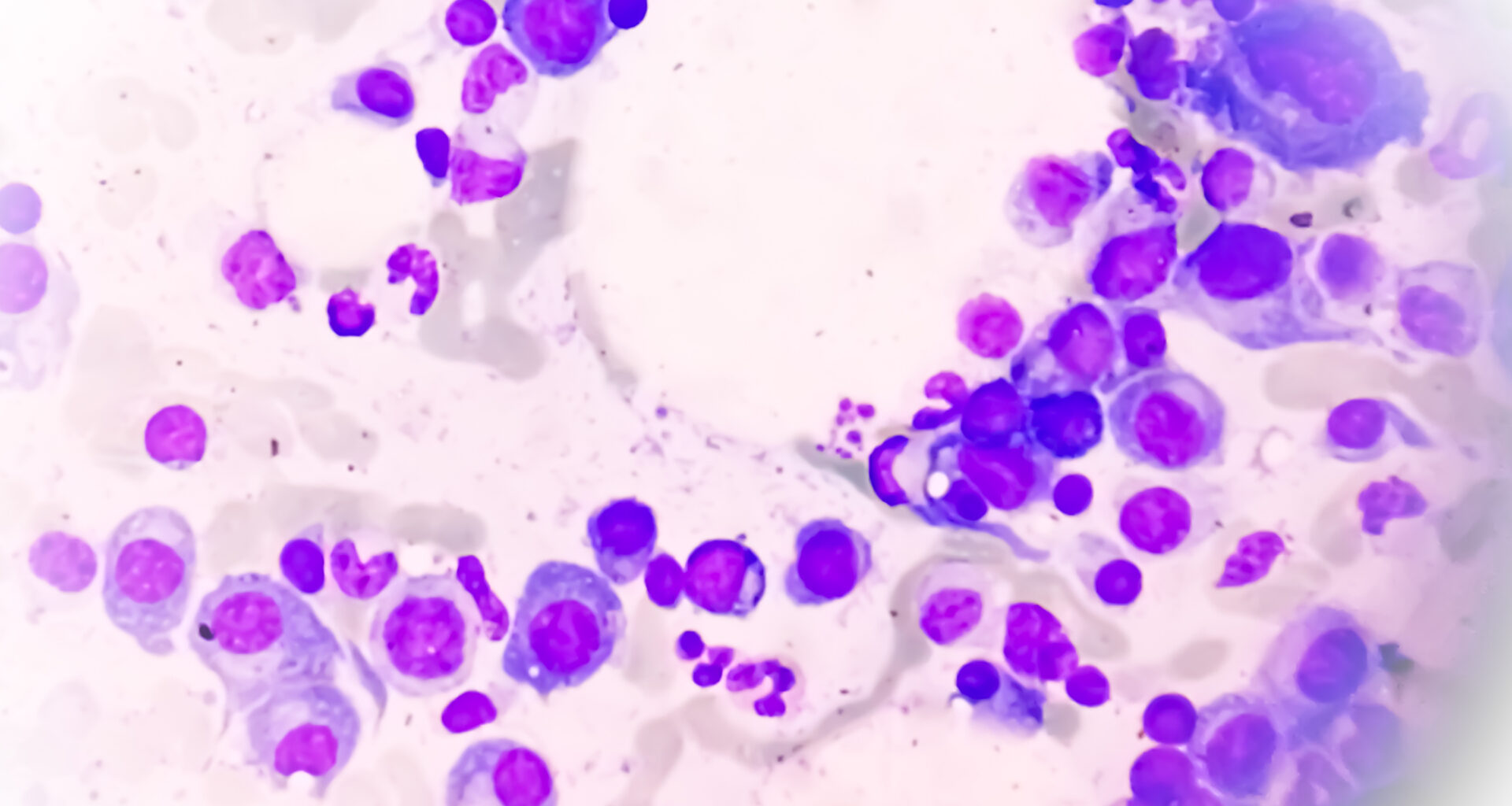

Credit: Md Saiful Islam Khan / iStock / Getty Images Plus

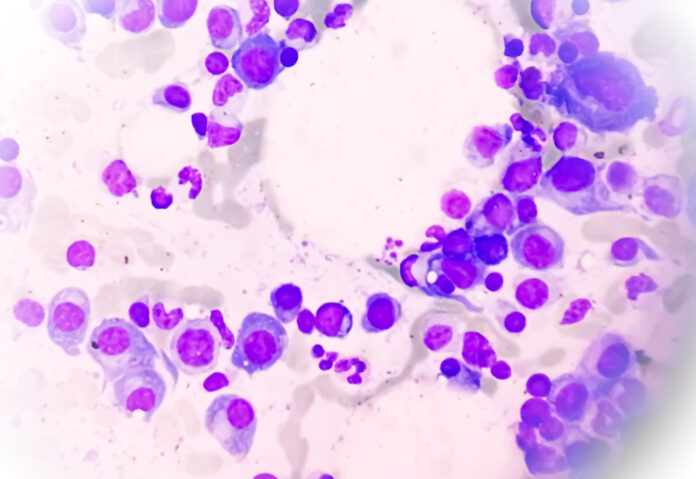

Credit: Md Saiful Islam Khan / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Scientists across six leading U.S. institutions have created the largest single-cell immune cell atlas to date, using data from over a million bone marrow cells sourced from multiple myeloma patients. A study published today in Nature Cancer shows that evaluating the immune system’s response to myeloma could complement traditional genetic testing to improve predictions of which patients are at a high risk of relapse after treatment.

“Currently, doctors rely heavily on the genetic features of cancer cells to estimate how aggressive their disease is,” said Sacha Gnjatic, PhD, professor of immunology and immunotherapy at the Mount Sinai Tisch Cancer Center and senior author of the study. “Our research shows that the immune cells surrounding the tumor are just as important in determining how the disease progresses, and this could lead to earlier, more targeted treatment strategies.”

Despite significant improvement in the treatment of multiple myeloma, including targeted and immune therapies, multiple myeloma remains an incurable disease. Current prognostic models based on genetic testing are still limited in their ability to identify patients at high risk of early relapse, suggesting that factors beyond the tumor’s genetic makeup could be determinant instead. With funding from the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF), Gnjatic and colleagues set out to study the immune system’s role in multiple myeloma outcomes, which still remained largely unknown.

The immune cell atlas was created using more than 1.1 million cells obtained from 263 newly diagnosed patients in the MMRF’s CoMMpass study dataset. Using single-cell RNA sequencing, the researchers examined the molecular features of each individual cell and unveiled key patterns in the immune system’s behavior linked to patient outcomes.

Results showed that patients who relapsed quickly after initial therapy had distinct immune features in their bone marrow at the time of diagnosis, before receiving any treatment. In particular, their T cells showed higher expression of senescence genes and their bone marrow microenvironment showed strong signs of inflammation. Communication signals shared between tumor and immune cells were also found to drive proinflammatory and immunosuppressive changes in participants with poorer outcomes.

These findings were then validated in another sample of over 240,000 cells from 74 participants, showing that integrating immune cell signatures with known tumor genetics significantly improves patient stratification and survival predictions.

Although the immune cell atlas has been developed for research purposes, the researchers hope that findings derived from it could inform the development of simpler tests that can be broadly implemented in a clinical setting down the line.

“This work not only provides new biological insights, but also lays the groundwork for future discoveries,” said Gnjatic. “It could help researchers around the world better understand how the immune system interacts with cancer and ultimately, help improve outcomes for patients.”