Researchers have uncovered chemical evidence that humans in what is now South Africa were using poisoned arrows for hunting as far back as 60,000 years ago (Sci. Adv. 2026, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adz3281).

“As far as I know, it is the earliest evidence of using arrow poisons” and perhaps even the earliest direct evidence of humans deliberately using poison, says Sven Isaksson, an archaeologist at Stockholm University and coauthor of the study.

The analysis was part of a project aimed at studying prehistoric humans’ cognitive and technological evolution in southern Africa, led by the study’s other coauthors, Anders Högberg of Linnaeus University and Marlize Lombard of the University of Johannesburg.

Lombard noticed that several of the Pleistocene-era quartz arrowheads she was working with from Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter in South Africa had a visible residue on them. She wondered if it might be early evidence of poison lacing, so she contacted Isaksson to do chemical analysis.

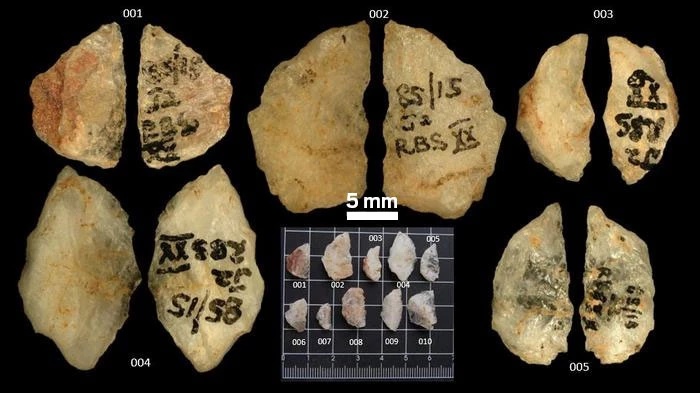

Stone arrowheads from an archeological dig against a black background.

These five Pleistocene-era stone arrowheads contained traces of plant poisons, which indicates that early humans were using poisoned weapons for hunting.

Credit:

Sci. Adv.

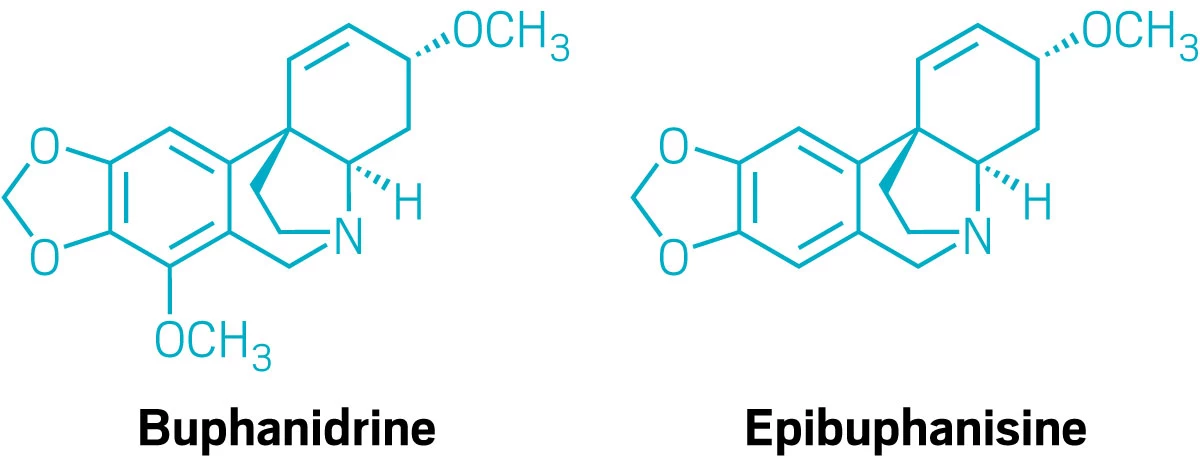

Isaksson used gas chromatography/mass spectrometry to characterize the residues from 10 prehistoric arrowheads; 5 contained traces of buphanidrine, a toxic alkaloid characteristic of native amaryllis species such as Boophone disticha. One arrowhead residue also contained epibuphanisine, a related compound. B. disticha is locally known as “poison bulb,” and there’s extensive documentation of Indigenous people in the region using extracts from the plant as an arrow poison.

Isaksson compared the artifacts to poisoned hunting arrows made in the same region in the 18th and 19th centuries CE and to extracts from B. disticha. These more-recent samples contained high levels of buphanidrine and epibuphanisine, along with several other alkaloids that Isaksson had identified as potential biomarkers of arrow poison from the region.

Although the researchers had been explicitly looking for poison biomarkers, Isaksson says it was still a pleasant surprise to actually find them because the artifacts were so old. The alkaloids’ simple, rigid structure and minimal reactive sites helped them stand the test of time.

Ester Oras, an archaeochemist at the University of Tartu who was not involved in the work, calls it “really groundbreaking” research that combines chemistry, archaeology, local ecology, and Indigenous knowledge to tell “a really solid story” about Stone Age arrow poisons. She adds that it is especially impressive that the researchers were able to pinpoint the plant family the residues came from. “In many ways, it’s kind of a lucky case” that the chemical analysis dovetailed with the historical and ethnographic records surrounding B. disticha.

Chemical structures of buphanidrine and epibuphanidine, two plant-derived alkaloids.

The animals that these arrows would have been used against are probably similar to what people hunt in the region now: antelope, wildebeests, possibly zebras or giraffes, Lombard says in an email. Though poison arrows couldn’t kill instantly, they could weaken the animals to make them easier to bring down.

“Although the ancient bowhunters probably did not know the chemistry of their poison . . . they clearly had enough practical and technical knowledge to identify, extract, and apply” it, which represents impressively advanced cognition, Lombard says.

Hunters had to know what plants to use, how to prepare them, and how long it would take for the animal to show symptoms of the poison. “It’s behaviors that point to sophisticated, cognitive, cultural, behavioral capacities. So it adds to the concept that these are modern people,” Isaksson says.

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2026 American Chemical Society