Back in 2017, in the early days of Leo Varadkar’s period as taoiseach, he was fond of referring to Ireland as “an island at the centre of the world”.

It was a phrase that reflected both Varadkar’s facility for a catchy soundbite but also Ireland’s good fortune in the second half of the 2010s, as it emerged with accelerating pace from the period of post-crash economic gloom. Connections to the EU, the US and, increasingly, with China, positioned Ireland in a uniquely advantageous position.

Nowadays, the world looks very different. It looks more threatening, less co-operative, more uncertain – a world where small nations can get trampled by the big beasts of the geopolitical jungle. The island at the centre of the world is in danger of being sucked down the plughole.

But there are opportunities, too. This week, Taoiseach Micheál Martin was in China, where his hosts stressed their desire for Ireland to be a bridge between their country and the EU, a relationship that has been increasingly troubled in recent years.

In two months, Martin will travel to Washington DC for the annual St Patrick’s Day ceremonies with US president Donald Trump. This week, EU leaders were warning Trump not to take over Greenland, the territory of an EU and Nato member state, by force. Who knows where EU-US relations will be by then?

Meanwhile, as he contemplates the competing geostrategic rivalries, Martin is facing continuing unrest in his own party, as reports over Christmas make clear that party rebels are in no mood to move on from their grievances of last year.

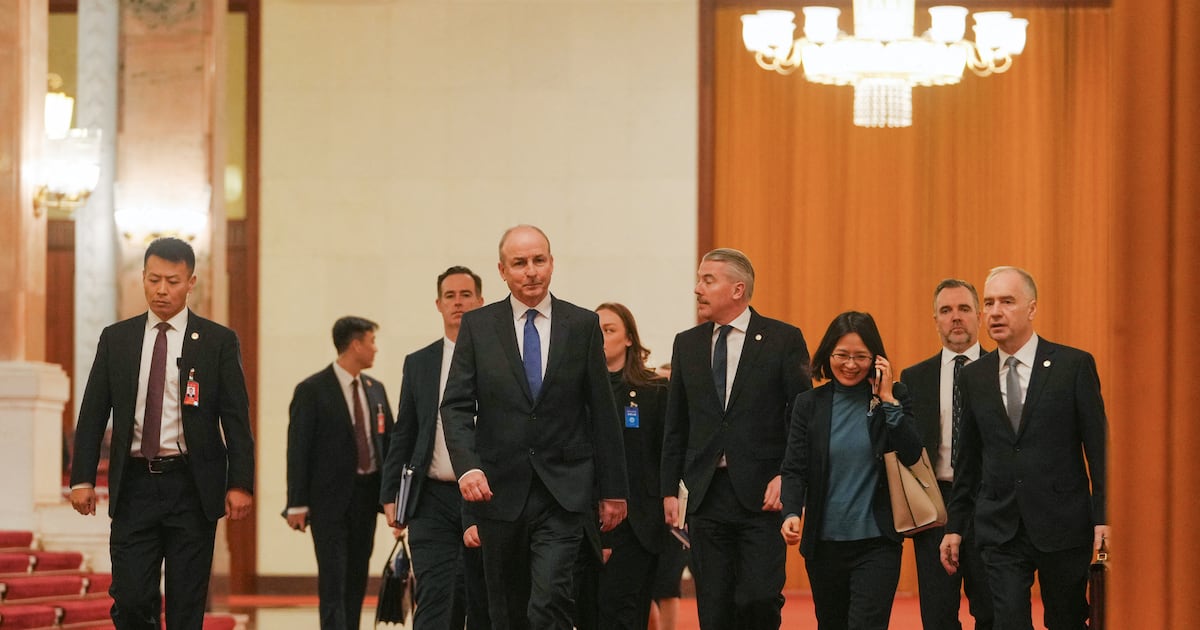

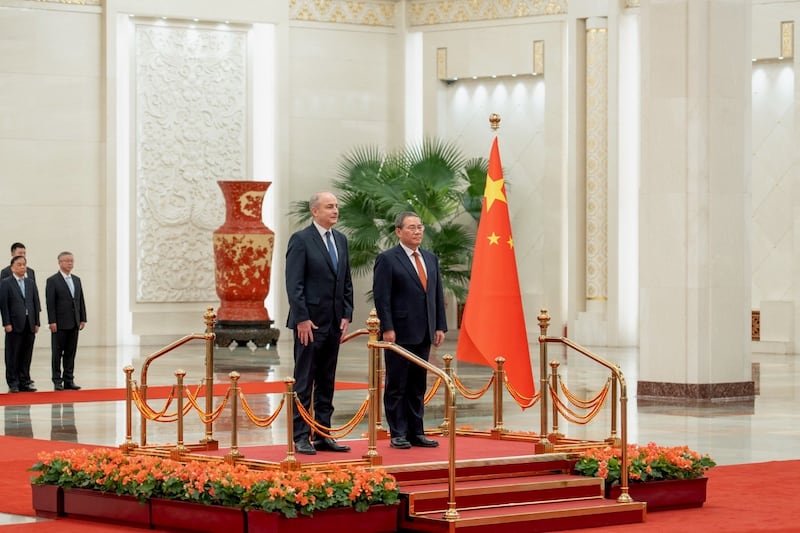

Martin with Chinese premier Li Qiang in Bejing on January 6th. Photograph: Government of Ireland/PA Wire

Martin with Chinese premier Li Qiang in Bejing on January 6th. Photograph: Government of Ireland/PA Wire

Reports from China this week, including in The Irish Times from Denis Staunton, made clear that the Taoiseach was given the “super red carpet treatment” by the Chinese government, including meetings with the three most senior politicians in the administration.

The Taoiseach received full ceremonial and military honours at the Great Hall of the People on Tuesday when he met premier Li Qiang. Earlier, he met Zhao Leji, the chairman of the National People’s Congress, China’s legislature. Most significantly of all, Martin had a bilateral meeting on Monday with Xi Jinping, the essential, dominant figure in China’s government for more than a decade.

“Both China and Ireland are peace-loving, open-minded, inclusive, self-reliant, and enterprising. The people of both countries won national independence and liberation through struggle, and have relied on generations of continuous efforts to move towards modernisation,” Xi told the Taoiseach in his prepared remarks.

“China is willing to strengthen strategic communication with Ireland, deepen political mutual trust, expand pragmatic co-operation, seek benefits for the people of both countries, and add impetus to China-EU relations.”

State-backed Chinese media also portrayed the visit as an opportunity to reset the EU-China relationship, with Ireland as a “bridge” between the two.

A lot of the conversations seemed to be about the EU-China relationship. Beijing wants a new framework and while Martin appeared to like the idea, it’s not entirely clear what it means. The EU is critical of China for its support of Russia in Ukraine, but there is also deepening worries in the EU, especially Germany, about Chinese competitive threats to European manufacturing.

Martin was cautious: he said he was open to China’s suggestion of a new framework for the EU-China relationship but said it was for the European Commission and EU member states to determine how to proceed. He was optimistic about food exports to China from Ireland and said that China was keen to invest in wind energy off the Irish coast.

Martin said he raised human rights issues, though clearly not in a way that offended his hosts, and pooh-poohed security concerns about Chinese links with Irish universities. Nothing was allowed to spoil the chummy tone of the encounters.

But Ben Tonra, Professor of International Relations at the UCD School of Politics and International Relations is sceptical about the idea of Ireland as a “bridge”.

“I think it would be going way too far to describe Ireland as a bridge between the EU and China,” he said.

“The Chinese are looking for bridgeheads in Europe. Ireland is seen as one of a small number of EU member states that are possible bridgeheads, countries that are a bit more sympathetic to it … They may think that the route through national capitals is far more likely to be productive than through Brussels.”

Tonra was surprised that the Taoiseach waived away the question of security concerns over the extent of co-operation between universities in Ireland and China. “It goes against everything the EU is saying and everything his own Government is saying,” he said.

Martin and his wife Mary O’Shea in the Oval Office of the White House with US president Donald Trump in March 2025. Photograph: Doug Mills/New York Times

Martin and his wife Mary O’Shea in the Oval Office of the White House with US president Donald Trump in March 2025. Photograph: Doug Mills/New York Times

The St Patrick’s Day visit to the White House is two months away but it is already occupying the minds of some in Government Buildings. Last year, Martin’s visit – his first as Taoiseach to see Donald Trump – came in the wake of the infamous Oval Office ambush of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskiy by Trump and his vice-president JD Vance. The first EU leader to visit Trump in the White House since his inauguration, Martin faced a daunting prospect; getting out of there alive would be counted as a victory.

Stress levels in Dublin in advance of the visit were in the stratosphere. What if Martin was subjected to the Zelenskiy treatment? What if he was tackled on Ireland’s pro-Palestinian stance? What if Conor McGregor turned up?

In the event, the St Patrick’s Day visit went remarkably smoothly, with warm words in the Oval Office (“I’m gonna call him Mee-haul … coz that’s his name”) and later on Capitol Hill, before the party returned to White House for a raucously good-humoured evening reception. The sighs of relief from the Taoiseach’s party when it was all over could be heard back in Turner’s Cross.

This year may prove trickier. Trump is clear about his ambitions to take control of Greenland; that could be nothing other than a red line for the EU, and all its members. Martin might be able to dodge his way around questions about Venezuela; but there would be no way around Greenland. Is there any question of not going? Absolutely none, says one senior official.

But who knows where things will be between Trump and the EU in two months’ time? Trump is nothing if not unpredictable. And one person familiar with the terrain thinks that Ireland should recognise its own importance to the US as an interlocutor with the EU.

Brett Bruen, a former director of global engagement at the Obama White House and who now serves on the board of the Clinton Institute at UCD, says that Ireland is one of the US’s only “truly close confidantes” in the EU.

“I think that card is underplayed by Dublin,” he says.

Trump may be “bulldozing in public”, Bruen says, “but behind closed doors he and his advisers are striking a somewhat different tone.”

Ireland, says Bruen, is in a position to play a role in thrashing out some sort of a compromise on Greenland. There’s a “deal to be done,” he says, though he warns it has to be “flashier and faster”.

“Trump doesn’t want a process,” he says. “He wants a prize.”

Ben Tonra is less optimistic. “I think things are going to get stickier before they get easier,” he warns.

And Eoin O’Malley, professor in political science at the School of Law and Government, Dublin City University, is sceptical of the whole idea of Martin navigating a course between the superpowers.

“The Taoiseach’s trip to China seems to be designed to peel Ireland off from the EU pack. We’re also meant to be ‘derisking’ from our dependence on China for manufacturing. This trip and the noises around it hardly seem consistent with that goal,” he says.

“And we’re so deeply linked to the US both economically and culturally that we can’t go too far in criticising the US without risking the still rising corporation tax returns. So it will be hard for him to keep all those plates in the air,” he says, adding: “Something will have to go wrong soon.”

Juggling the threats and opportunities of a rapidly reshaping world, Martin’s position at home has been significantly weakened by the debacle of the presidential election and the tensions in his own party that resulted. There is a group of declared rebels in his parliamentary party, while the decisive middle ground does not want him to be leader at the next election.

This week, his backbenchers sent coded and not-so-coded warnings to him on the Mercosur treaty. If he was minded to vote for or even abstain on the Mercosur trade agreement, as his comments in China hinted, a wave of opposition from his own TDs – and independents in Government – showed him that he does not have complete freedom of action as Taoiseach.

As 2026 dawns, Martin’s position is not exactly precarious; but nor is it unambiguously secure. Sometimes, it’s lonely in the middle.