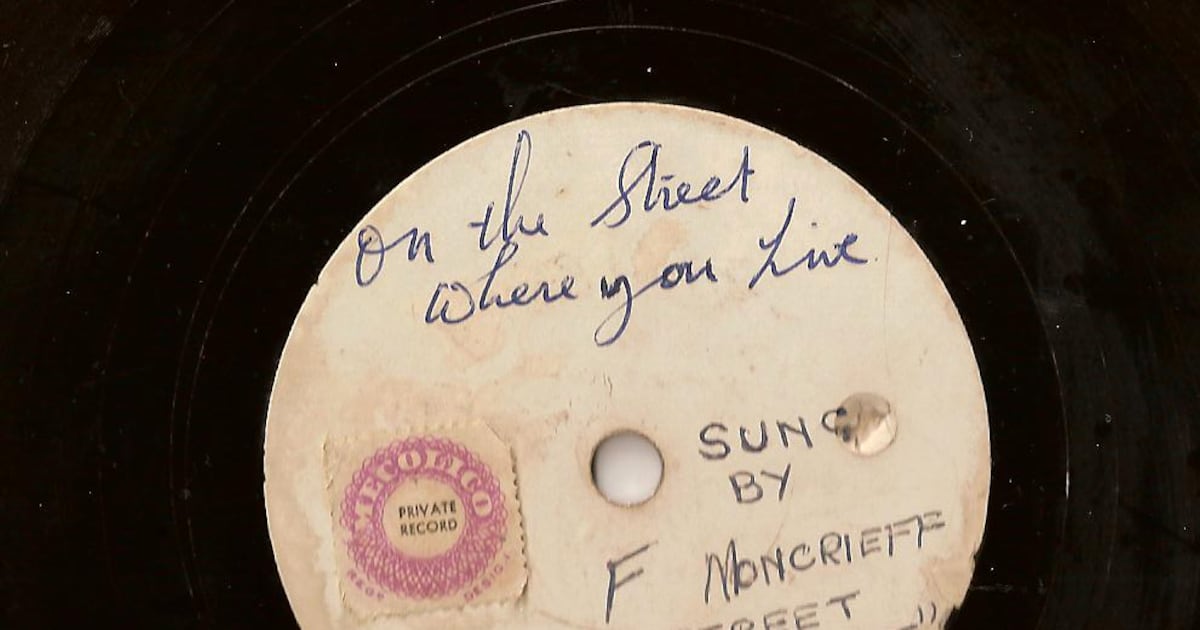

Sometime in the 1950s, my father went into a studio in London and recorded a song.

Back then anyone could rent an hour in an extremely basic studio to sing a song or recite a poem. They came away with a heavy 78 record with a stamp from Mecolico (The original Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society) that read “Private Record”.

In my father’s case, it was a recording of him singing – accompanied by a piano – On the Street Where You Live from the film/musical My Fair Lady. It’s usually performed at a jaunty pace, as an optimistic song. But my father’s version is slower, more mournful. Things might not work out.

He had, as he often said about other singers, a good set of pipes, and for a time in London supplemented his income by singing in bars and restaurants; the guy in the corner who might get a decent round of applause, or might be completely ignored, depending on how drunk the clientele were.

I don’t think he ever secretly dreamed of stardom. He was far too realistic for that. It was a way of making a few extra pounds in the evening. But that’s not to say that he didn’t enjoy it, that there may have even been something mildly thrilling about it. I like to think that’s why he made the record: his brief showbiz career preserved for two minutes and 38 seconds.

Of course, he never said any of that. The record was always there, in the various homes we lived in. It was occasionally played on a record player we had that looked more like a briefcase. But he never explained why he made it. When I was old enough to ask, he would wave the question away: as if the reason was far too silly for anyone to want to hear. When I was an adult and I’d ask him about the record, he claimed he’d lost it. Then he claimed it was broken.

We found it after he died, stuffed in a box in the garage among piles of bric-a-brac and old furniture they should have donated years before. It was filthy and scratched.

Yet I seized upon it. In the face of implacable death, even the illusion of doing something pushes back the grief a bit. I brought it home, cleaned it the best I could, then bought a cheap record player which would convert it to an MP3. The sound was awful. The original recording wasn’t great to begin with – one microphone in an echoey room – but the years had added all manner of whistles and screeches. I put it through various editing programmes in an attempt to purge all the background noise and ended up with something marginally better than awful. It still sounded like he was singing through an aural fog: like time itself was muffling his voice.

I still listened to it, though. It’s been on my playlists for the past 15 years. There’s a big note he does at the end, and every time I get a little anxious that he might not make it. He always does.

But occasionally, the recording vexes me and I go back and fiddle with it again. Over the years the technology has improved and I’ve managed to scrub out a lot of the background noise. Yet it was only in the past few months that I thought about using AI.

There are loads of websites that will allow you one free go. Some of them made him sound Martian, but one managed, more or less, to separate his voice from the tinny piano. And after a bit more tweaking, there he was: his voice reaching me across all that time. A young version of my father that I never knew and who had yet to meet me, who was unaware that seven decades later, his son would get to fully hear him.