NASA has announced a new mission to study the Sun. The Chromospheric Magnetism Explorer (CMEx) was chosen over four other mission concepts that competed in earlier studies.

A team in Boulder, Colorado wants CMEx to monitor the Sun’s chromosphere, a restless layer above the visible surface.

The work is led by Dr. Holly Gilbert at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) where she studies solar magnetism and eruptions.

NASA wants CMEx to capture the first continuous magnetic-field observations in the chromosphere, helping trace how solar eruptions start.

Scientists call the solar wind, a nonstop stream of charged particles, a major driver of space weather near Earth.

CMEx and solar storms

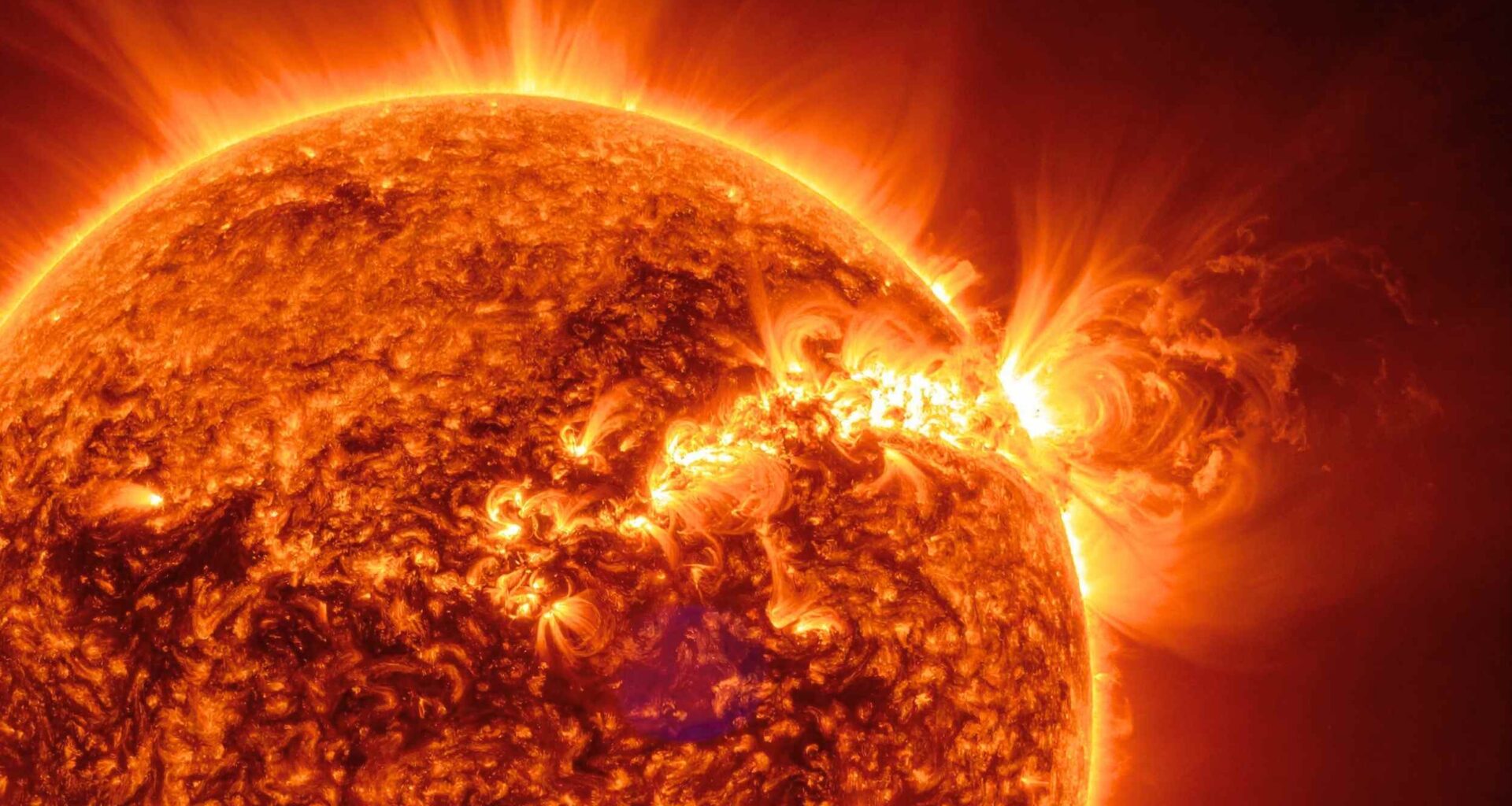

Solar storms often begin when stressed magnetic fields snap into a new shape, releasing stored energy as heat and fast particles.

One common event is a coronal mass ejection, a huge cloud of charged gas and magnetic fields, that can race toward Earth.

The Sun’s upper atmosphere stays in plasma, gas with free electrons and ions, so magnetic fields push and pull it.

Steady watching is essential because the chromosphere can change within minutes, and brief snapshots can miss the buildup before eruptions.

Ground telescopes face weather and daylight limits, so scientists rarely track chromospheric magnetic fields for many hours in a row.

A long-running review notes that magnetic fields drive flares, heat upper layers, and accelerate the solar wind.

Reading polarized light

Measuring subtle patterns in polarization, the direction a light wave vibrates, allows scientists to infer magnetic forces on the Sun.

Scientists use spectropolarimetry, measuring polarization across different colors of light, because magnetic fields tweak those signals at specific wavelengths.

Ultraviolet lines from the chromosphere can carry clearer magnetic fingerprints, since the light forms where atoms feel local field strength.

NASA tested similar ultraviolet polarimetry on a short suborbital flight called CLASP, which targeted hydrogen Lyman-alpha light.

That CLASP test used a sounding rocket, a brief research rocket that reaches space, to prove sensitive optics can survive launch.

CMEx would build on CLASP heritage to watch for months, letting researchers compare quiet periods with stormy days.

What CMEx will study

Tracking how magnetic structures rise from the Sun’s surface into the chromosphere and then into hotter layers reveals how eruptions develop.

Scientists call the interplanetary magnetic field, solar magnetism carried outward by the solar wind, a link between Sun and Earth.

Better chromospheric measurements could pinpoint where open magnetic lines form, since open fields let solar wind escape more easily.

Turning data into forecasts

These data would feed computer models that forecast space weather, changing conditions from the Sun, before storms reach Earth.

Forecast models work best when heliophysics, science of the Sun and near-Earth space, teams start with magnetic maps that show energy in loops.

Earlier warnings give satellite controllers time to switch modes and grid operators time to reduce risky power flows.

Large geomagnetic storms can drive currents through long transmission lines, since shifting magnetic fields induce electricity in metal loops.

Engineers call a geomagnetically induced current, electricity forced through wires by changing fields, a reason transformers can overheat.

The 1989 storm knocked out power across Quebec, and about 6 million people lost electricity for hours.

Satellites in the crosshairs

Solar storms can disturb the magnetosphere, Earth’s magnetic bubble that deflects solar wind, raising drag on low satellites as the atmosphere expands.

Radio signals pass through the ionosphere, an electrified region high above Earth, and storms can bend or block them.

Fast particles can charge satellite surfaces, and sudden voltage jumps can upset electronics or trigger protective shutdowns.

CMEx and astronaut safety

Astronaut crews face extra risk during bursts of solar energetic particles, high-speed radiation from the Sun, that can damage cells.

Mission planners use forecasts to time spacewalks and route flights, because shielding has limits against the hardest radiation.

This capability could improve warning lead time for these bursts, since better magnetic tracking helps predict where acceleration will occur.

More small missions

Placement within NASA’s Explorers Program requires NCAR teams to keep budgets tight and schedules short so new measurements reach researchers sooner.

Competition in this program forces teams to reuse proven hardware, which lowers risk and leaves more room for science.

Successful Explorer missions often seed bigger observatories later, because early datasets reveal what instruments and orbits work best.

Next steps for CMEx

The project still must pass design reviews and also must fit within mass, power, and pointing limits.

Instrument teams must balance cadence, how often the instrument records a measurement, with signal quality because faint polarization demands longer exposure times.

Other satellites will still be needed to track storms through space, since CMEx would watch only the Sun.

NASA’s decision keeps the project and NCAR in active development, while teams refine the spacecraft design and plan for a future selection.

For anyone who depends on radios, satellites, or power lines, this work promises clearer warnings as scientists map the Sun’s chromosphere.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–