After trying out algorithmic trading on a quantum computer, HSBC recently joined a growing list of companies to claim that a revolutionary new form of computing was finally coming into its own.

The experiment was a “world first in bond trading” that showed “we are on the cusp of a new frontier of computing in financial services”, the bank said.

Some quantum experts are not so sure. Scott Aaronson, a professor of computer science at the University of Texas, dismissed it as one of an increasing number of “zombie claims” of quantum computing’s superiority.

“There’s absolutely no reason to believe any improvement they saw had anything to do with quantum mechanics,” Aaronson said. Even HSBC’s own researchers wrote that they were not able to explain how the IBM machine they used had achieved the superior trading results, adding that their work “requires further investigation”.

HSBC’s claim comes amid a spate of announcements during the past few months that quantum machines have achieved results beyond the capability of traditional, or “classical”, computers — a hotly anticipated milestone known as quantum advantage or quantum supremacy.

But there has been intense disagreement over which, if any, of the claims is valid. And even if the reports turn out to be scientifically sound, it may take many more years of work before the machines become commercially useful.

“There’s an awful lot of jumping on the bandwagon,” said Bob Sutor, a former head of quantum computing at IBM. “Sometimes it feels to me like people are just rushing to get into the history books.”

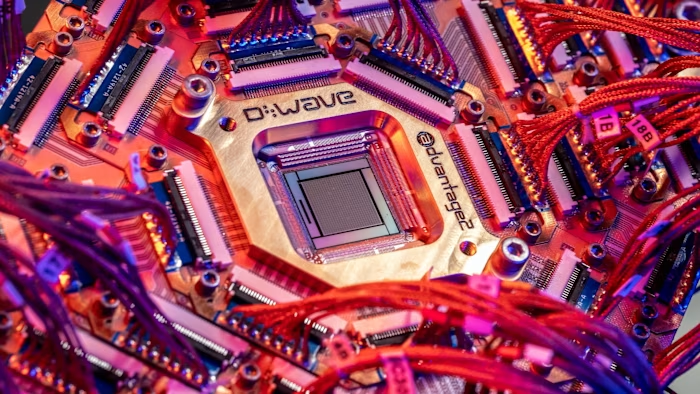

Companies to report passing the all-important quantum milestone include Google, with an algorithm that could lead to the development of entirely new materials, and D-Wave, whose technology tackles extremely complex optimisation problems.

Quantinuum said it had achieved promising results experimenting with superconductors at room temperature © Quantinuum

Quantinuum said it had achieved promising results experimenting with superconductors at room temperature © Quantinuum

In November, Quantinuum said it had achieved promising results experimenting with superconductors at room temperature, while three groups of researchers working on IBM’s quantum machines released details of experiments they said appeared to have reached the critical technical threshold.

Experts admit that assessing these claims is difficult. One problem is that quantum advantage is a moving target: using new techniques, programmers of classical computers have sometimes been able to match or overtake the supposedly superior quantum systems.

That makes establishing the superiority of a quantum computer like “trying to prove a negative”, Aaronson said.

Since Google’s first claim of quantum supremacy in 2019, traditional computers have leapt ahead. Even Google executives concede that a problem they once said would take a classical computer 10,000 years could now be done in 200 seconds.

Sabrina Maniscalco, chief executive of Finnish quantum software company Algorithmiq, said her company “can claim we are breaking all the classical benchmarks so far” with a quantum algorithm used to simulate new materials.

But she added there was no way to tell whether someone would find a way to do even better using a classical machine, and that it would take time for the two different computing worlds to agree on areas in which quantum systems might truly excel.

To head off challenges to its latest claim, Google said it had taken the unusual step of “red-teaming” its results, or enlisting a team of researchers to exhaustively try to disprove its own results.

According to Aaronson, the tech giant is among the companies with the best claim so far to have achieved quantum advantage, along with Quantinuum and QuEra.

Jay Gambetta, head of IBM research, said quantum advantage was similar to the point artificial intelligence reached in 2012, when the first breakthrough results in computer vision emerged © Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images

Jay Gambetta, head of IBM research, said quantum advantage was similar to the point artificial intelligence reached in 2012, when the first breakthrough results in computer vision emerged © Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images

To try to break the cycle of claims and counterclaims, IBM in November backed the launch of a website to track possible examples of quantum advantage, releasing three initial cases — including the one from Algorithmiq — for others to test.

“I would say the results that we put out are very close,” said Jay Gambetta, head of IBM Research.

Yet even if the experts manage to agree on cases where quantum computers actually outperform today’s machines, the systems may still be a long way from solving practical problems or justifying the speculation that boosted the stocks of publicly traded quantum companies last year.

Early claims of technical superiority rested on being able to generate circuits with complete randomness, a scientific demonstration without practical uses.

More recently, most of the work has turned to algorithms that could one day be applied to real-world problems, often involving the simulation of materials at the atomic level, which themselves exhibit the properties of quantum mechanics.

Today’s quantum computers, however, are too small to conduct these calculations with the precision that would be needed to make their results useful.

That makes quantum advantage similar to the point artificial intelligence reached in 2012 with the first breakthrough results in computer vision, said IBM’s Gambetta. “The first neural networks were not actually meaningful, but they were significant scientific demonstrations that have now evolved into huge amounts of computation,” he said.

With the industry potentially at an important threshold, quantum companies say they are turning their attention from scientific research to more pragmatic concerns.

“We’re starting to realise what you really want to be talking about is economic value — building a machine that actually has impact on the world,” said Nate Gemelke, chief technology strategist at QuEra. That moment could be anywhere from two years to a decade away, he predicted.

Recommended

The timing depends heavily on whether useful results can be generated from today’s “noisy” quantum systems, where interference between the basic components, known as qubits, makes it hard to carry out a coherent calculation.

If not, it will take a new generation of “fault-tolerant” quantum systems. IBM and Google are both racing to build these by the end of this decade, though many experts believe practical fault-tolerant quantum computers will take years longer.

That has not stopped companies from trying to coax something useful out of today’s machines. For some, achieving empirical results that seem superior to anything possible on a traditional computer is reason enough to test the boundaries, as HSBC claimed after its bond trading experiment.

But unequivocal evidence that quantum mechanics has been harnessed to solve real-world computing problems is likely to take longer.

“I would be happy to be surprised, but for [quantum] results I can prove, we need a fault-tolerant quantum computer,” said IBM’s Gambetta.