Most magnets are predictable. Cool them down, and their tiny magnetic moments snap into place like disciplined soldiers. However, physicists have long suspected that, under the right conditions, magnetism might refuse to settle even in extreme cold.

This restless state, known as a quantum spin liquid, could unlock new kinds of particles and serve as a foundation for quantum technologies that are far more stable than today’s fragile systems.

At Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), researchers have now created and closely examined a new magnetic material that brings this strange possibility a little closer to reality, even if it doesn’t quite cross the finish line yet.

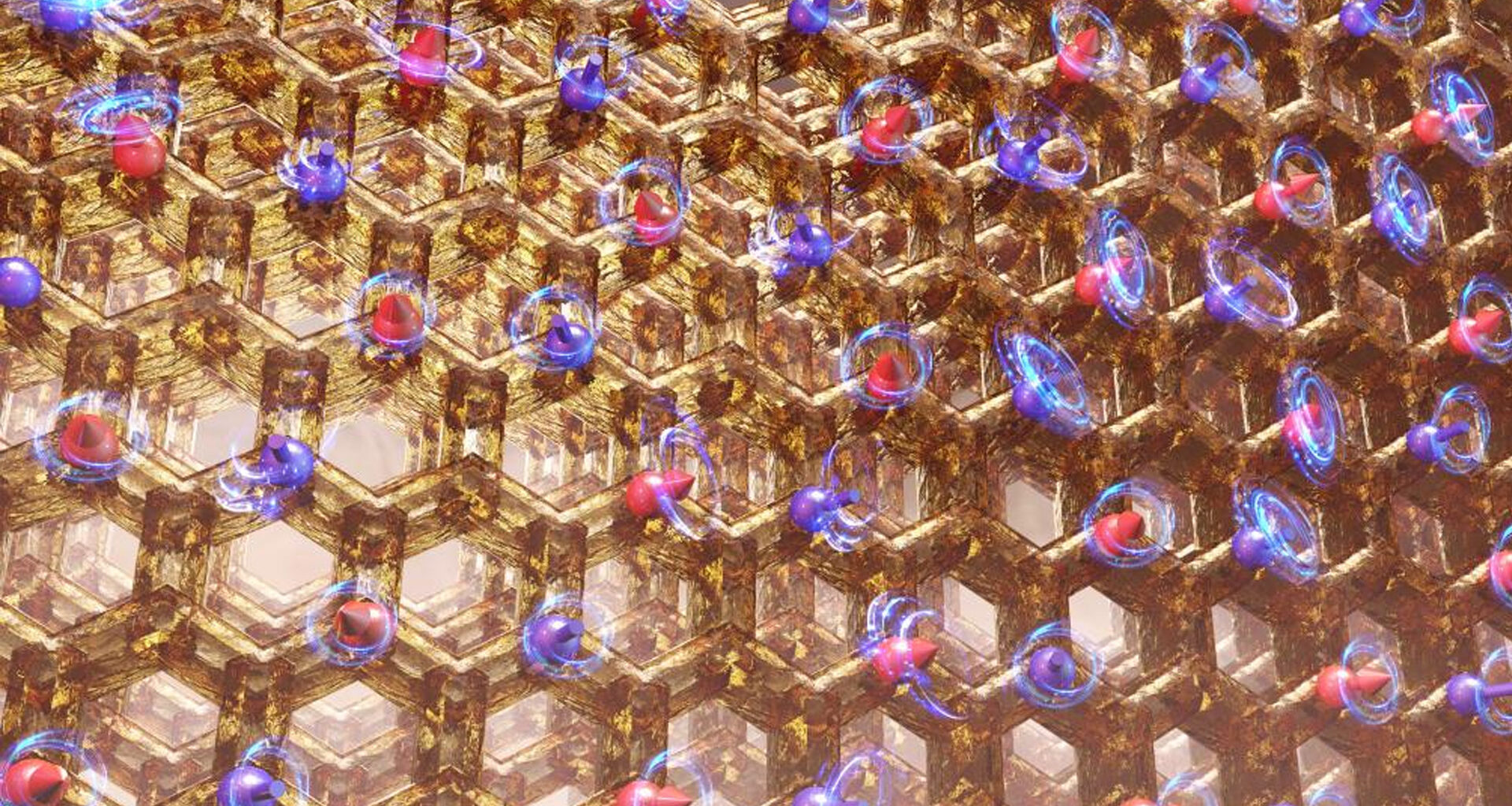

Crafting a delicate honeycomb of spins

The difficulty with quantum spin liquids is that nature prefers order. In ordinary magnetic materials, unpaired electrons behave like tiny compasses and eventually align with one another. To prevent this alignment, the interactions between spins must compete in very specific ways.

Nearly twenty years ago, physicist Alexei Kitaev proposed that a honeycomb-shaped lattice of magnetic atoms could produce exactly this kind of competition, but turning this idea into a real material has proven exceptionally hard.

The ORNL team focused on a compound called potassium cobalt arsenate, where cobalt atoms form a two-dimensional honeycomb network. Making it required unusual care. Heating the ingredients too much would cause the compound to fall apart before it could form crystals.

The researchers solved this by slowly heating a carefully prepared solution at low temperatures, allowing crystals to grow without decomposing. Once the material was made, the team subjected it to a battery of tests.

Chemical analysis confirmed the exact proportions of potassium, cobalt, arsenic, and oxygen. Electron microscopy and diffraction revealed that the honeycomb lattice was real, but not perfectly symmetrical. That slight distortion turned out to matter.

Measurements of heat capacity and magnetism showed that, as the material cooled, the cobalt spins eventually locked into an ordered pattern below about 14 kelvin (around −259 °C), rather than remaining fluid as a quantum spin liquid would.

Neutron scattering experiments provided the clearest picture of what was happening inside the crystal. Since neutrons interact strongly with magnetic spins, they allowed the researchers to confirm that the honeycomb structure was consistent throughout the sample.

Presence of weak Kitaev interactions

Meanwhile, computer simulations based on the measured structure explained why the spins froze. The exotic “Kitaev” interactions were present, but weaker than more conventional magnetic forces. In other words, the physics predicted by the theory was there, but not strong enough to dominate.

At first glance, falling short of a quantum spin liquid might seem like a disappointment. However, in this field, getting close is often more valuable than getting lucky.

The potassium cobalt arsenate material sits near a tipping point. Calculations suggest that changing its chemical makeup slightly, squeezing it under pressure, or applying strong magnetic fields could shift the balance between competing interactions.

If that balance can be tipped, the reward could be profound. Quantum spin liquids are expected to host unusual collective excitations called Majorana fermions—entities that are not individual particles but shared quantum motions spread across the material.

“The Kitaev model has served as a long-sought-after target in the realization of a quantum spin liquid that could host Majorana Fermions,” the study authors note. Since these excitations are naturally protected from noise, they are considered promising building blocks for future quantum computers and sensors.

In short, the honeycomb the researchers have built may not yet host a quantum spin liquid—but it offers a practical route toward one, and that alone makes it a valuable step forward.

“Computational studies suggest the presence of a weak nearest-neighbor Kitaev term, K1, consistent with related honeycomb cobaltates. Together, the data suggest that this material should present a new platform for developing Kitaev quantum spin liquids,” the study authors added.

The study is published in the journal Inorganic Chemistry.