According to researchers from an international collaboration, light may loop through space, making telescopes unknowingly observe the same region more than once, similar to how reflections behave in a hall of mirrors.

The findings come from the Collaboration for Observations, Models and Predictions of Anomalies and Cosmic Topology (COMPACT), a team focused on reexamining the possible topological shape of the universe. While local measurements show the observable universe is flat, or nearly flat, the study highlights that its global structure remains unknown. The analysis challenges earlier interpretations of Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) data, reopening the possibility that the universe could have a finite but boundary-less structure, such as a torus.

Although the shape of the universe is one of cosmology’s most enduring questions, COMPACT researchers argue that existing tools have not yet ruled out all possible Euclidean topologies. Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, states that the CMB may support simple but exotic shapes, and suggests that much broader investigations are still possible.

Previous Assumptions About Topology Are No Longer Enough

COMPACT’s study builds on a premise often taken for granted: that the universe is either infinite or so vast that its edges are unreachable. But the group focused on whether the universe’s shape can create mirrored observations through finite, repeating structures. According to Popular Mechanics, they concentrated on the 3-torus shape, essentially a flat but folded structure that loops back on itself.

In a hypertorus model of the Universe, motion in a straight line will return you to your original location, even in an uncurved (flat) spacetime – © ESO/J. Law

In a hypertorus model of the Universe, motion in a straight line will return you to your original location, even in an uncurved (flat) spacetime – © ESO/J. Law

The study examines three variations of the 3-torus topology: E1, E2, and E3. The first, E1, represents the standard model and can be excluded if its dimensions fall within the limits of the observable universe. However, E2 and E3 involve spatial twists, 180 degrees and 90 degrees respectively, and remain viable under current data. These shapes could, in theory, create conditions where regions of space are visible from multiple angles without contradicting existing CMB observations.

The researchers state: “While unambiguous indicators of topology have yet to be detected, we present evidence that prior searches for topology have far from exhausted the potentially significant possibilities.” Their findings indicate that previous studies may have been too narrow in scope, and that more complex structures could still match the data.

The Illusion of Cosmic Duplicates Remains Unresolved

One of the consequences of a twisted, finite universe would be a “hall of mirrors” effect, where light travels in loops across space. Telescopes could end up observing the same cosmic region more than once, with the images appearing in different parts of the sky. This idea, long considered speculative, is no longer dismissed outright.

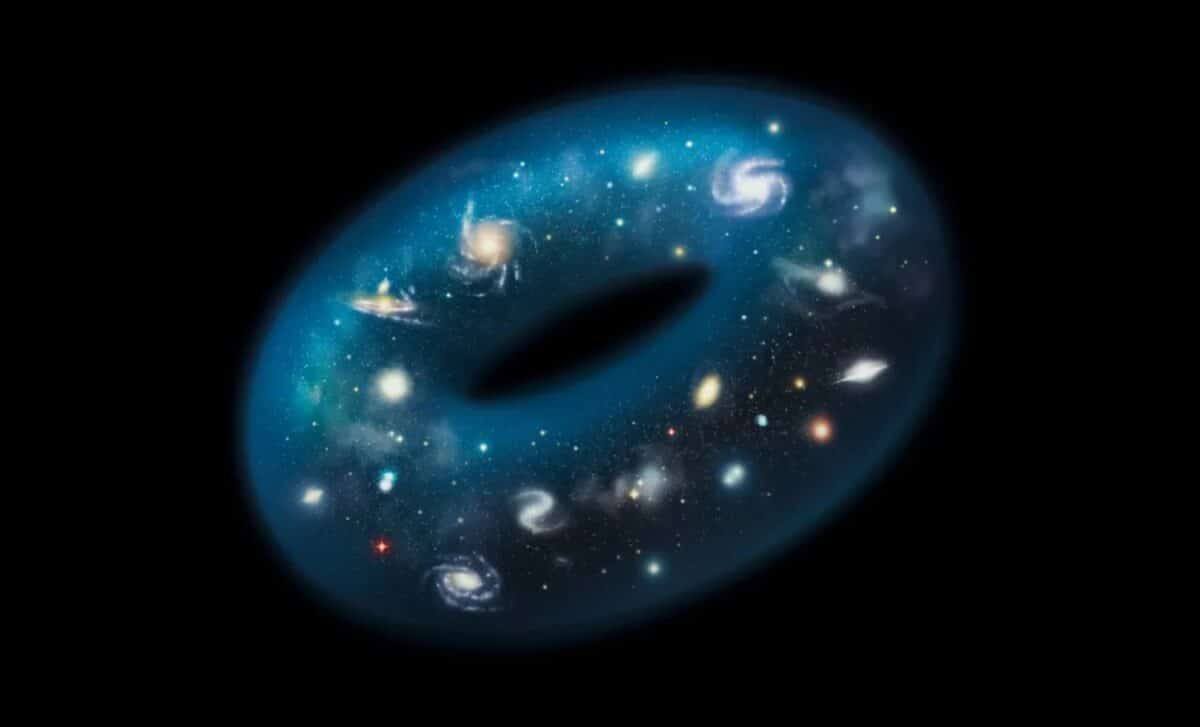

A visualization of a 3-torus model of space, where our observable Universe could be just a small portion of the overall structure – © Bryan Brandenburg/Wikimedia Commons

A visualization of a 3-torus model of space, where our observable Universe could be just a small portion of the overall structure – © Bryan Brandenburg/Wikimedia Commons

No observable evidence has confirmed such illusions. But that lack of evidence may be misleading—light from distant mirrored regions could still be in transit, beyond the CMB horizon. The researchers stress that this possibility doesn’t refute the theory; it simply highlights the limits of current observation.

According to a report from the American Physical Society, regions viewed through a twisted loop would show correlated but non-identical images. These correlations could eventually serve as topological fingerprints, allowing scientists to determine the shape of the universe through direct comparison.

Narrowing the Search for Topological Evidence

Rather than testing all 18 mathematically possible topologies, COMPACT’s paper focused on the E1-E3 variants as a starting point. This targeted approach reflects a shift in methodology: rather than relying on elimination, the researchers are now searching for unique patterns in the data that can positively identify a structure.

The work does not yet offer definitive answers. Instead, it lays out a framework for future research that looks deeper into Euclidean and non-Euclidean models. If topological fingerprints can be found in the CMB, they could confirm or eliminate specific shapes, including those more complex than E2 or E3.