As oceans warm, many marine species are being squeezed into shrinking habitats, with coastlines cutting off their paths to cooler, safer waters.

When that escape fails, the losses spread beyond wildlife – disrupting food supplies, livelihoods, and the coastal protection that healthy seas provide.

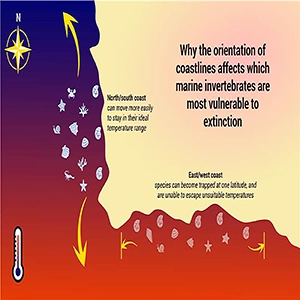

Researchers at the University of Oxford found a simple pattern. Across shallow seas, east-west coastlines are linked to higher extinction risk, while north-south coasts offer safer escape routes.

The work was led by Dr. Cooper Malanoski, who used fossils to map extinctions. His research focuses on how geography and climate set up boundaries for marine life, especially during rapid warming.

Simple, map-based clues give conservation planners a new way to spot marine populations that may run out of habitat.

Fossils reveal long-term risk

To follow extinctions across the Phanerozoic, the last 540 million years of complex life, the researchers relied on fossil occurrences worldwide.

The team analyzed over 300,000 fossils spanning more than 12,000 genera, groups of closely related species, drawn from shallow-marine animals.

The fossils were matched to paleogeography – reconstructed ancient positions of continents and coastlines – so each range sits in its original setting.

A statistical model then compares who survives in different shoreline layouts, but fossils still miss soft-bodied groups and some regions.

Species get stuck by latitude

Along an east-west coast, animal groups can move far while staying near the same latitude.

The key risk comes from latitudinal traps, places where moving north or south is hard, even when nearby waters cool.

Islands and inland seaways create dead ends because open water or land blocks a direct route toward cooler zones.

When warming pushes preferred conditions away, that geometry turns a local problem into a species-level risk across generations.

Moving north or south

Previous evidence suggests that survival depends on whether species can move into cooler waters as the climate warms.

North-south coasts ease that movement because crossing latitude bands changes temperature, keeping organisms within thermal tolerance – a safe range for body function.

“This reduces their risk of extinction,” said Professor Erin Saupe of the University of Oxford.

Infographic describing the study’s findings. Credit: Getty Images, Public Affairs Directorate, University of Oxford. Click image to enlarge.Warming and extinction risk

Infographic describing the study’s findings. Credit: Getty Images, Public Affairs Directorate, University of Oxford. Click image to enlarge.Warming and extinction risk

Species in these traps may also fail to mix genes with cooler-water populations, limiting adaptation when change arrives quickly.

Extinction risk from trapped coastlines grows during mass extinctions and during warming intervals.

That pattern also strengthens in hyperthermal intervals, episodes of unusually warm global climate, when ocean temperatures rise beyond what many species endure.

“This shows how important palaeogeographic context is: it allows taxa to track their preferred conditions during periods of extreme climate change,” said Dr. Malanoski.

If modern warming speeds up, coasts that limit latitude change may create the same bottleneck for reefs and fisheries.

Seas become dead ends

Some ancient oceans had coastlines packed with bays and inland seas, and a 2023 model links that layout to higher vulnerability.

Plate motion can close seaways and open others, changing which margins connect to cooler waters and which ones become enclosed.

Modern examples include the Mediterranean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, where complex coasts and nearby land make travel routes indirect.

As continents keep drifting, the same region can flip from corridor to trap, changing long-term risk for resident lineages.

Fossil limits remain

Even a huge fossil sample leaves gaps, and a 2024 review warns that preservation skews which species appear.

Hard shells fossilize more readily because minerals resist decay, so soft-bodied animals can vanish without leaving a clear record.

Time bins can also blur rapid events, since a layer may mix fossils from thousands of years into one snapshot.

Those limits mean the coastline signal is strongest as a relative warning, not a precise forecast for any single species.

Species are shifting

Modern warming is already moving marine ranges. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report summarizes the pattern across many studies.

Since the 1950s, typical poleward movement is 32 miles per decade near the surface and 18 miles per decade near seafloors.

Currents, oxygen levels, and seafloor shape can steer that movement, so some populations must choose between deeper water and new latitude.

For animals living in bays or enclosed seas, that choice may not exist, and local extinctions can build quickly.

Protection from coastline traps

Long-term fossil work shows that geographic range often predicts who disappears, so narrow distributions deserve extra attention.

Managers can map which coasts offer a direct north-south route, because that corridor lets populations follow temperatures without crossing land.

Where barriers dominate, protection may need to focus on local refuges, since nearby cooler habitats could be unreachable during heat waves.

That approach will still leave tradeoffs, because reducing fishing or pollution can buy time but cannot remove the geographic lock.

Taken together, fossils, coastlines, and climate history point to movement as a survival tool that geography sometimes blocks.

Future work can test living populations in enclosed basins, while conservation plans consider where warming leaves no clear exit route.

The study is published in the journal Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–