Photo-Illustration: The Cut; Photo: Getty

I’m in grippy socks and a paper gown, and it’s 4 a.m. and absolutely no one in the labor-and-delivery triage area is worried about me. But one of the nurses is at least compassionate or seems so. I’m relieved I haven’t met her before, given it’s my third visit here this week. She must be new. She doesn’t suggest I’m wasting everyone’s time as she readjusts the fetal heart monitor. I study her sparkly Crocs and the crucifix around her neck and ask if she has children. “Three,” she tells me. A few of the nurses don’t bother hiding their eye rolls anymore, so I make a point of seeking out the friendly ones who call me “sweetie” or “honey” because they feel sorry for this woman who they are certain has lost her mind.

But I haven’t lost my mind. For example, I alternate between the two main hospitals in my small southern city to give the medical staff at each one a break from me. Since I entered the second half of my pregnancy, I have been to each unit more than a dozen times.

I’m strapped to a monitor in a hospital cot, pretending I can decipher some meaning in the machine’s beeps and whirs. Some nights that I’ve felt propelled to the hospital, my husband has refused to come with me. On the edge of tears himself, he has said he feels he’s enabling an illness. My response has been both resentful (How could he do this to me?) and relieved (Of course he’s right).

But tonight, my husband waits calmly for my release from across the room. He’s almost as exhausted as I am, having driven us down a deserted predawn highway. I watch the printed graph of my child’s heartbeat unspool into rolls of zigzags on the hospital floor. Hospital staff come and go. The ones I haven’t met before stare at me confused. “The baby looks good.” “The baby is probably fine.” “Statistics are in your favor.” “No amount of monitoring will ensure a healthy baby,” they all tell me. Their platitudes multiply like cells. Intellectually, I know they are right. But OCD, my lifelong roommate, insists I keep checking.

They’re preparing my discharge paperwork now. I’m told that everything looks good. “Well, that’s a relief,” my husband says. He’s not being sarcastic; it just sounds that way. He’s thinking that the only silver lining here is that the nearby Whataburger is open 24/7. He knows I will sit in the drive-through analyzing my after-visit summary as we await our milkshakes.

Leaving with a clean bill of health again will be humiliating, but it’s better than what awaits at home. I know with certainty that intrusive thoughts will return. What if I fall asleep and fail to notice that the baby has stopped moving? Is four kicks an hour normal, or is it five? If I feel only four in two hours, is she slowly losing oxygen? Is that a somersault? Is the umbilical cord strangling her? Isn’t that move unnaturally forceful — desperate? See, she is in distress. I knew it.

After my husband collapses back into bed and my dogs sniff me curiously, I go to the refrigerator and select the most sugary drink I can find — orange juice or chocolate milk — to induce fetal movement. I open the cupboard and scoop some peanut butter into my mouth. I slink into the spare room so that I can have some privacy: I prefer to do my rituals unobserved, in the pitch-dark. I lie on my back and clench my jaw, tears coming into my eyes as I try to will my daughter to start kicking. There, that is one. I wait in suspense for the second. It seems like it’s taking longer between kicks than usual. But what does “usual” mean when a baby is constantly growing? I grab my phone and start researching fetal movement. I see the same websites and message boards I’ve read before, but I reread the posts that nauseate me the most, daring myself to face potential catastrophes. Now, I’m also afraid I’m leaking amniotic fluid, even though I already had the nurses test for that just a few hours ago. I go to the bathroom and use an amniotic fluid test strip I ordered off Amazon. The baby isn’t moving enough. Is she just sleeping? Isn’t she supposed to be awake at night? Or is she just supposed to be awake when I am sleeping?

I don’t sleep. Once I’ve tested for fluid, I pull out the handheld Doppler that I had asked my husband to hide from me, but I know all of his hiding places. I’m weeping softly now, trying to find the heartbeat, but all I hear is static and bumping noises. I wonder if the nurses have changed shifts and I can return to the hospital with minimal shame. I finally find the heartbeat, but the reading I catch seems too high. I Google tachycardia again. The URLs I have visited before have gone from blue to purple, screaming out how many times I have clicked on them. Since the Doppler is making me more anxious, I take out an old fetal monitor that I convinced my doctor to give me. It no longer has paper to record the zigzags, but I can listen to my baby’s heartbeat for hours, and I often do. It’s big and clunky and reminds me of the typewriters I grew up around in the ’80s. I smear ultrasound gel that I ordered off Amazon on my belly and press the outdated and barely operative fetal monitor to my abdomen. I can’t stop crying. I’m so tired that I feel cold. I need to rest. I wish I could stop. But my daughter needs me more. I chase her like a fish in a vast, unknowable ocean — her flickering, teasing presence.

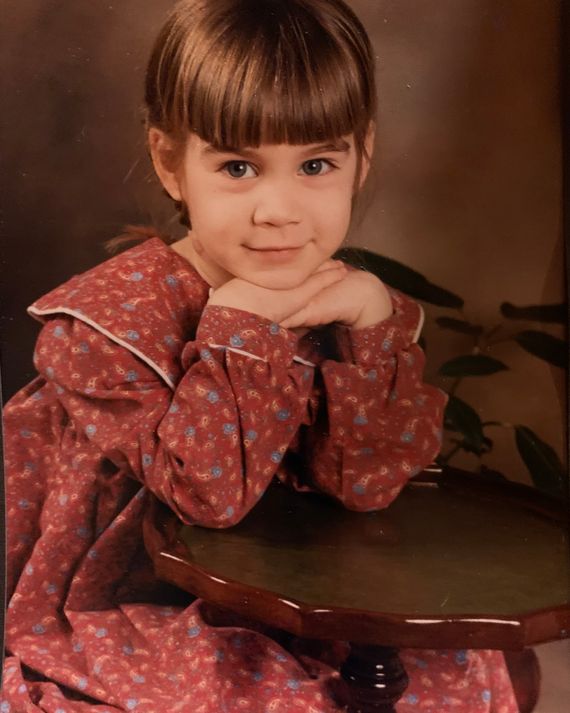

The author at age 4, right before she began to develop symptoms of OCD.

Photo: Courtesy of Emily Leithauser

I have suffered from OCD since I was 5 years old and learning to write letters. I remember noticing that the t looked like the crucifix I had seen when my family occasionally went to church. It occurred to me that if I didn’t make the t on my worksheet look symmetrical, I would be punished — for disrespecting God, I suppose. Soon I found myself tracing t shapes in the foggy glass of the double doors leading to the principal’s office, too. Did anyone notice that I was rooted to the spot, unable to move because I had to trace every near-invisible shape I saw, reaching on my tiptoes, trying to keep my index finger steady? If I didn’t do this, something terrible might happen — my family might die, or I might never fall asleep again, or a plane somewhere halfway across the world would crash and it would all be my fault.

Around that time, the kids in my class became fascinated by the story of Bloody Mary. Even now, as an adult who knows better, something catches in my throat as I write this. The legend went that if you turned several times in front of a mirror in the middle of the night, a full glass of water in hand, Bloody Mary would come out of the mirror and scratch you all over, leaving bruises and marks on your body. In the beginning, every time I saw a mirror, I looked away. Then, at some point, I could no longer drink water out of regular glasses nor sleep over at friends’ houses if they had mirrors in their bedrooms. Looking back, I think what scared me almost as much as the spectral figure of Mary was the idea that the spell was cast through numbers. I believed that if you turned twice instead of three times, she could be confined to the shadowy prison of the mirror — but that she was still waiting to escape. Anyone with OCD understands the particular allure of quantification.

I was officially diagnosed with OCD at age 9 in a therapist’s office in a small college town in Massachusetts. Back then, in the early ’90s, exposure therapy was a popular treatment for OCD. My particular focus was a fear of germs and public restrooms, so my doctor gave me a key to the semiprivate bathroom in her office suite. Once I’d conquered using that bathroom without freaking out or washing my hands repeatedly, I graduated to using a big public one in another area of the building. Exposure therapy works much like inoculation. If you are exposed to the thing you most fear and the worst doesn’t come to pass, you slowly realize, through repeated practice, that your fear was exaggerated, even fantastical. If you can stand the discomfort, even the anguish, of choosing not to perform a ritual, your intrusive thoughts begin to change accordingly, decreasing in frequency and intensity. It doesn’t work for everyone, but exposure therapy enabled me, in my adolescent years, to manage OCD with minimal disruptions. The urgency and power of my childhood fixations began to dim with time. I thought I was better.

But about ten years later, in September 2001, I started college, two planes hit the Twin Towers, and my OCD returned with ferocity. Suddenly, I was afraid of bombs, planes, and anthrax. My roommates stared at me in horror as I scrubbed my mouth with hand soap, convinced I’d ingested anthrax from a sealed envelope in my campus mailbox. My hypochondria worsened, as did the feeling that I personally had to prevent terrorist attacks from occurring. I saw someone stuff what was probably a sandwich bag into a Barnes & Noble trash can, and then I couldn’t focus, imagining that the person had planted a bomb and that I would be the one who did nothing. I informed the staff, and the entire bookstore was evacuated. Don’t they always say “If you see something, say something”? But it felt like I was always “seeing” things and that I couldn’t trust my own vision.

Around the same time, I convinced myself I was actually losing my vision, visiting the student health center for what I worried was a detached retina. The eye doctors I followed up with politely informed me that they tend to see these injuries in football players and in the elderly. It would be highly unusual for an 18-year-old woman who didn’t participate in any contact sports to develop this problem. Then, in my freshman Psych 101 class, I became an utter cliché, convincing myself after reading my textbook that I had the beginnings of schizophrenia. I remember putting coins in the dorm laundry machine, my textbook in front of me, and hearing the blood pound in my ears as I discovered that schizophrenia was often comorbid with OCD and tended to manifest in young people.

After visiting a counselor, I was funneled into an OCD study at Massachusetts General Hospital, where therapy was free and where I filled out countless questionnaires. But I was suffering, and I quickly got tired of being a guinea pig. So I left the study, and a psychiatrist family friend convinced me to try Prozac. Somehow, all of this time, I had never been medicated. As I stood in my childhood bedroom wondering if I would have to drop out of college because I couldn’t function, a close friend told me I would feel better soon. She said that SSRIs worked slowly and then all at once; she compared them to flowers that bloom overnight but that you can’t observe growing or opening.

The Prozac worked. I felt hugely better. I threw myself into college, made friends, and dated. I wrote an honors thesis, got a research grant to study in Paris, and then went on to earn a master’s degree and a doctorate. I learned to be a teacher. I fell in love and had my heart broken, and fell in love again and had my heart broken again, and then fell in love once more. I published a book of poetry. I got married.

I began a tenure-track position at a liberal-arts college. We bought a house. I got pregnant and had a miscarriage at 11 weeks, after seeing a heartbeat weeks earlier. I lapsed into grief and then committed myself with renewed dedication to getting pregnant again. I succeeded.

Though I spent much of my childhood picturing worst-case scenarios, it never crossed my mind that pregnancy might be especially hard for me. But even for women who don’t suffer from OCD, pregnancy can feel scary and suspenseful. Several of my close friends who don’t have mental-health diagnoses have had moments of real terror and vulnerability while pregnant, spiraling over worries about miscarriage, stillbirth, or genetic conditions. In my case, these understandable fears, with the catalyst of OCD, alchemized into a toxic mixture. The illness that had waxed and waned, but that I’d mostly kept under control with Prozac, returned with a force that I had never experienced. Even in my most desperate moments at age 9 and again at 18, I never felt unsure, as I did while pregnant, about whether I could survive what my brain was putting me through.

Part of the reason my OCD exploded during my pregnancy is that my doctor told me to stop taking Prozac in my first trimester. I did what he said because I was so scared of a second miscarriage, even though there’s no compelling evidence to suggest that SSRIs factor in to pregnancy loss. I can still recall looking out the window from his office at the pedestrians below and envying people who were not pregnant for their ability to move through the world unencumbered. I felt claustrophobic in my own body.

It was my husband’s birthday, and I was around 20 weeks pregnant when I first felt my baby move: a tapping and rolling motion, like something turning over. The panic came a few days later, when I was walking with my mother and husband in an art museum staring at ancient artifacts. “I felt the baby a few days ago, but I haven’t felt her since. Did she die?” I asked them, tears in my eyes. Doctors had already warned me that expecting daily, consistent movement at this stage would be unreasonable. But my mind couldn’t help circling to the last days of my previous pregnancy, when I’d walked in the sunshine from the parking lot to the building where I taught and the phrase “my body is a graveyard” ran through my head on a loop.

By 24 weeks pregnant, many women are told to start tracking their baby’s movements; their OB/GYN mentions it in an appointment or they read about counting kicks in a pregnancy book as a way of preventing stillbirth. The advice has been reinforced by our app-flooded, data-drunk culture, and at first I was excited to have something concrete to measure. But when my doctor informed me that I had an anterior placenta, meaning movements would be more muffled and harder to discern, obsessions began to take over. I tried an app called “Count the Kicks” for a while, because it felt like externalizing my motherly intuition. But soon the app wasn’t enough, because I wasn’t content to count once or twice a day. Instead, I was counting almost every minute I was awake. I managed to keep teaching by pacing during my classes; I didn’t expect to feel the baby while I was walking, so moving kept my spiraling thoughts temporarily at bay. If my students noticed my restless body language, they didn’t say anything.

Friends and family tried to help me. They answered frantic texts at all hours, begged me to medicate or meditate, researched OCD and pregnancy, and by turns argued and agreed with me. I had a smart therapist who understood how badly I was suffering as I showed up, wild-eyed, to our sessions. My midwife was also sensitive and thoughtful and tried to reassure me that there is no universal, one-size-fits-all system for movement tracking. “Get to know your baby,” she said. “Know what is not normal for your baby.” My OB/GYN even put me back on a low dose of Prozac, but it had no impact. Everyone wanted to help, and to a woman more capable of living in a gray area, this might have been comforting. But I found myself believing that if I only concentrated hard enough, I could understand all the mysteries of my child’s behavior. Lying in a fetal position chugging pineapple juice, I would repeat my friends’ words, but they didn’t feel as true to me as the inner voice telling me to count, to check, just one more time.

One day, pacing the indoor track at the gym, I called several friends, lobbying them to find me a spalike psychiatric facility for expectant mothers and have me committed. I was fantasizing about something Californian and sunny, with support animals, a doting medical staff, and round-the-clock analysis of my fears. Hooked up to a monitor, I would enlist nurses to help me count baby kicks. My loved ones would make pilgrimages to see me swaddled in comforting surveillance.

“That place doesn’t seem to exist,” one of my friends diplomatically pointed out, after a deep dive on Google. “But I think it’s great that you’re at the gym.”

Near the end of my third trimester, I took matters into my own hands: I went to the hospital and refused to leave. The nurses didn’t know what to do, so they gave me a sleeping pill, which I never would have taken without medical surveillance. I was hooked up all night, lying on my side in a hospital bed, and able to relax for the first time in months. If the baby stopped moving and died, it would be on their watch, not mine. I needed a break from vigilance and self-torture.

The next morning, my doctor came in, visibly angry. He told me that he and my psychiatrist had spoken. I told him I didn’t feel I could leave. He scheduled another ultrasound to give me reassurance but insisted that it was time to go. And though I left, I felt determined to come back very soon.

Weeks later, while my husband was at a Mardi Gras party I had refused to attend with him, I drove to the hospital and stayed overnight again. At 37 weeks, I was full term, and my mind was made up: I would not go home.

Later that night, despite his misgivings, my husband joined me at the hospital. The OB on call was sympathetic and seemed to think it might be possible to induce me early. When she called my doctor, he vetoed the idea but allowed for an additional ultrasound. The tech informed us that the baby was showing signs of low energy and reduced movement, but that there was most likely no cause for alarm. Still, they decided to keep me another night for monitoring. My husband went home to get some rest; he had work the next day.

In the morning, a Monday, he returned with the intention of bringing me home. But as a precaution, they performed a biophysical profile, a special kind of ultrasound combined with a non-stress test for high-risk pregnancies. For the first time, my baby failed the test. My doctor came in and told us we would have our baby in the next hour, because I needed an emergency C-section. I was stunned, horrified, and giddy. How was it possible that all of my unfounded obsessions had finally culminated in a measurable problem — a real, medical concern for the baby?

As I was wheeled into the OR, I felt hope for the first time in months. I wondered if it was possible that a new life — both for me and for my baby — was about to start. I was awake throughout the surgery, and I felt pressure but no pain. The doctors were chatting casually with each other. And then I felt something immeasurably heavy lifted out of me.

My doctor showed me the umbilical cord, which had two huge knots and had been wrapped several times around my daughter’s neck. The expression on his face was bizarre, almost sheepish. My husband and I read it as an admission — that maybe I had been right, after being wrong so many times. My OCD was real and destructive. But ironically, it may have saved my daughter’s life. I will never know for sure.

My husband was with our daughter in her first moments; she had a little trouble breathing but was healthy and strong and nearly seven pounds. My mother got on a plane and was there to hold her on her first day of life. Then, after four days of pumping colostrum and wincing as I hobbled to the bathroom, blood tumbling out in clots every time I stood up, it was time to go. We drove our daughter home so slowly. I remember a flood of euphoria. Now she was outside of me. Now I could see her. Now I would know if she was okay or if she needed help. Now other people could observe her too. She was no longer stuck in the black box of my body.

Back on the full dose of my SSRI, many of my obsessions vanished, and the arrival of more mundane fixations — Am I changing her diaper often enough? Is she getting enough milk? — was a welcome development. I had relapses, but after going to my daughter’s bassinet for the fifth time to check on her breathing or to make sure her swaddle wasn’t too hot or too tight, something in my brain allowed me to stop. Five was enough. No need for a sixth or seventh visit.

Of course, I was aware that the risks to our children only multiply as they grow. But my pregnancy had served as a rehearsal for those dangers — a kind of exposure therapy to larger unknowns. It had inoculated me, at least a little bit, to motherhood.

It’s no exaggeration to say I felt as if I had returned from far away to find my life waiting for me.

Emily Leithauser and her daughter.

Photo: Courtesy of Emily Leithauser

I had just started a new job in Atlanta and was the mother of a happy and active 2-year-old when I learned I was pregnant again, this time with a son. I told my therapist, and she immediately grew concerned. I could hear the fear in my parents’ voices, too. Everyone was afraid they would lose me again. I’m not going to go down this rabbit hole, I remember saying out loud in my office. I’m not going to lose my mind again.

Convinced, maybe unfairly, that another woman would be more likely to understand the profound responsibility and disorientation caused by a body gestating within my own, I sought out a female doctor. One of the first things she told me was that she would not be changing my SSRI prescription, and that we would closely monitor me for signs of my OCD reemerging. She was incredulous that I had ever been advised to stop my treatment. Together, my therapist and I came up with tactics to try to preempt OCD thoughts from taking over.

Still, when I reached 20 weeks and kick counting became plausible, I held my daughter on my lap and noticed that I couldn’t feel the baby inside — and the old panic resurfaced. I told myself that after I put her to sleep I could go to the hospital. But sure enough, as I grabbed the keys to the car and headed to the garage, I felt her brother again. With this pregnancy, I didn’t have an anterior placenta and the movements were much clearer.

So I went back inside, dropped the keys on my bedside table (close by, just in case), and crawled into bed next to my husband. For a few minutes, he counted with me — my face on his shoulder, our son kicking his back — and then we stopped.

Related