A promising—and powerful—new engineering breakthrough could soon enable researchers to alter the properties of materials by exciting electrons to higher-than-normal energy levels.

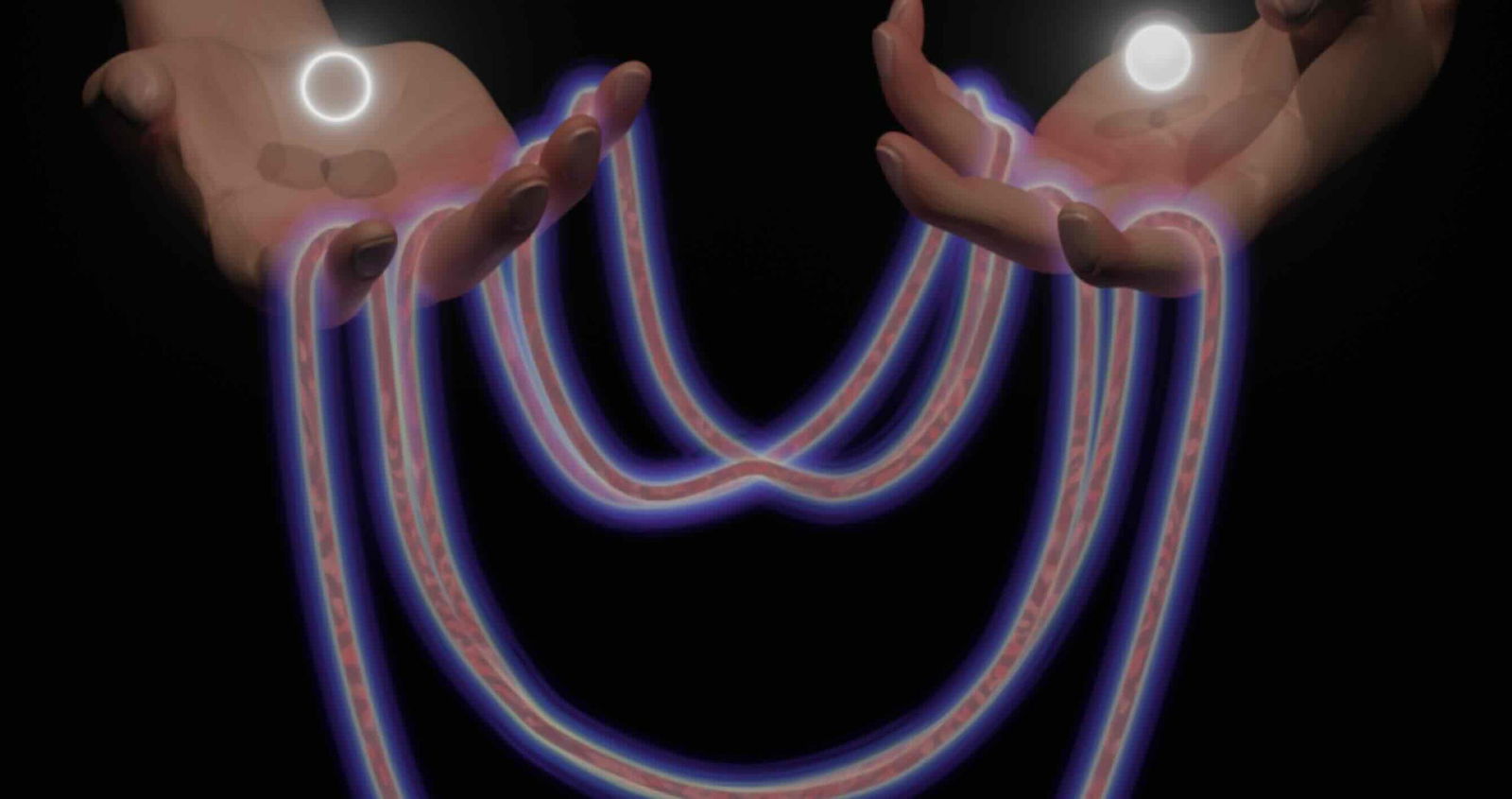

In physics, Floquet engineering involves changes in the properties of a quantum material induced by a driving force, such as high-powered light. The resulting effect causes the material’s behavior to change, introducing novel quantum states with properties that do not occur under normal conditions.

Given its promising applications, Floquet engineering has remained of interest to researchers for many years. Now, a team of scientists from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) and Stanford University says they have developed a new method for achieving Floquet physics that is more efficient than past methods that rely on light.

21st Century Alchemy?

Professor Keshav Dani, a researcher with OIST’s Femtosecond Spectroscopy Unit, said in a statement announcing the breakthrough that the team’s new approach leverages what are known as excitons, which have proven far more powerful in coupling with quantum materials than existing methods “due to the strong Coulomb interaction, particularly in 2D materials.”

Because of this, Dani says, excitons “can thus achieve strong Floquet effects while avoiding the challenges posed by light.” The team says this offers a novel means of exploring various applications, which include “exotic future quantum devices and materials that Floquet engineering promises.”

Such unique phenomena could enable material science applications that are almost akin to alchemy, in that the concept of creating new materials simply by shining light on them sounds more like science fiction than even the most advanced 21st-century engineering.

Floquet Engineering

In the past, Floquet effects have remained elusive in the lab, although investigations over the years have demonstrated their promise, provided they can be achieved under practical conditions. However, a major limiting factor has been reliance on intense light as the primary driving force, which can also lead to damage or even vaporization of the materials, thereby limiting useful results.

Normally, Floquet engineering focuses on achieving such effects under quantum conditions that challenge our usual expectations of time and space. When researchers employ semiconductors or similar crystalline materials as a medium, electrons behave in accordance with what one of these dimensions—space—will allow. This is because of the distribution of atoms, which confines electron movement and thereby limits their energy levels.

Such conditions represent just one “periodic” condition that electrons are subjected to. However, if a powerful light is shone on the crystal at a certain frequency, it represents an additional periodic drive, albeit now in the dimension of time. The resulting rhythmic interaction between light (i.e., photons) and electrons leads to additional changes in their energy.

By controlling the frequency and intensity of the light used as this secondary periodic force, electrons can be made to exhibit unique behaviors, which also cause changes in the material they inhabit for the time during which they remain excited.

From Light to Excitons

“Until now, Floquet engineering has been synonymous with light drives,” according to Xing Zhu, who is currently a PhD student at OIST. However, because light couples poorly with matter, researchers have been limited in the past to achieving such effects mostly at the femtosecond scale.

“Such high energy levels tend to vaporize the material,” Zhu says, adding that “the effects are very short-lived.”

“By contrast, excitonic Floquet engineering require much lower intensities,” Zhu says.

According to Professor Gianluca Stefanucci of the University of Rome Tor Vergata, one of the recent study’s co-authors, excitons are an ideal alternative to photons because they carry self-oscillating energy that can affect the surrounding material at frequencies that can be controlled through proper tuning.

“Because the excitons are created from the electrons of the material itself, they couple much more strongly with the material than light,” Stefanucci said.

“And crucially, it takes significantly less light to create a population of excitons dense enough to serve as an effective periodic drive for hybridization—which is what we have now observed,” he adds.

In the past, the OIST team has conducted exciton research using a specially designed setup called TR-ARPES, which stands for “time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy.” During experiments, the team excited a very thin, atomic-thickness semiconducting material with light, while recording the energy levels of the electrons within. This allowed the team to observe the manifestation of Floquet effects and, in addition, to measure electron signals at the femtosecond scale.

Significantly, this enabled the researchers to independently gauge Floquet effects associated with optical phenomena from those related to excitonic behavior.

“It took us tens of hours of data acquisition to observe Floquet replicas with light,” said Dr. Vivek Pareek, a Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow at the California Institute of Technology. Despite the amount of data required, the team was able to achieve excitonic Floquet effects, he confirms, “and with a much stronger effect.”

The team says their results prove that Floquet effects can be achieved under such conditions and that they can be reliably generated using a more formidable means (excitons, in this case) than light alone can provide. This opens the door to the potential use of such capabilities across a range of applications that could aid the development of useful quantum materials and devices.

Dr. David Bacon, the recent study’s co-first author, says he and his colleagues have “opened the gates to applied Floquet physics,” an achievement that is “very exciting, given its strong potential for creating and directly manipulating quantum materials.”

“We don’t have the recipe for this just yet,” Bacon added, though adding that “we now have the spectral signature necessary for the first, practical steps.”

The team’s research was recently detailed in the study, “Driving Floquet physics with excitonic fields,”

published in Nature Physics.

Micah Hanks is the Editor-in-Chief and Co-Founder of The Debrief. A longtime reporter on science, defense, and technology with a focus on space and astronomy, he can be reached at micah@thedebrief.org. Follow him on X @MicahHanks, and at micahhanks.com.