Astronomers have observed the effects of a rapidly spinning black hole twisting the motion of matter around it, a result widely interpreted by cosmologists as consistent with a century-old prediction of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. The finding is a striking achievement for modern physics. Yet philosopher Michael Kuznets argues that it also exposes a deeper tension at the heart of science itself: our most successful theories may excel at prediction while remaining silent about what the world is fundamentally made of.

Recent observations suggesting that a rotating black hole drags spacetime around with it have been widely hailed as another decisive confirmation of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. The phenomenon, known as frame dragging and more formally as the Lense–Thirring effect, was first predicted in 1918 as a consequence of Einstein’s equations for rotating masses. That it now appears to have been detected in one of the most extreme environments in the universe is, by any reasonable standard, a remarkable scientific achievement.

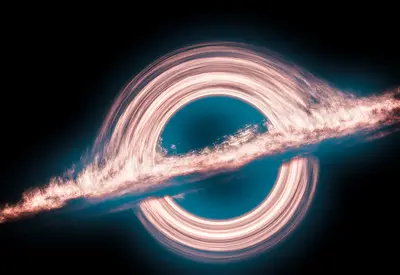

Astronomers using NASA’s Swift observatory together with the Very Large Array radio telescope have observed the disrupted orbit of a star as it interacted with a rapidly spinning black hole. The star’s motion exhibited a subtle but persistent wobble, consistent with the prediction that the black hole’s rotation twists the surrounding spacetime and alters the trajectories of nearby matter. This behaviour is precisely what general relativity predicts should occur if spacetime itself responds dynamically to mass and motion, and the observations provide some of the clearest evidence yet that this effect is real.

___

We can point out that despite the theory’s success, we still lack clarity about what spacetime is supposed to be, or whether it should be regarded as a fundamental constituent of reality at all.

___

It is, in this sense, another genuine success for the physics community. The result reflects decades of theoretical development, observational ingenuity, and collective effort, and it further reinforces the reliability of some of our most sophisticated mathematical models of the universe. It is therefore understandable that the discovery has been widely celebrated as yet another vindication of Einstein’s theory.

The philosophical significance of the result, however, is less straightforward than the headlines suggest. The central question it raises is not whether general relativity works, but what its success actually tells us. Put simply, the question is whether getting predictions right also tells us what the world is really made of. This distinction between ontological insight into what things actually exist and predictive utility, the predictive usefulness, of a theory is not a peripheral issue, it lies at the heart of how explanation operates in modern physics.

Some scientific realists take predictive success to be enough. On this view, the fact that general relativity continues to deliver correct predictions, even in extreme regimes, is strong evidence that its core claims about spacetime are at least approximately true. But some find this kind of conclusion premature. We can point out that despite the theory’s success, we still lack clarity about what spacetime is supposed to be, or whether it should be regarded as a fundamental constituent of reality at all. Just because we can explain how it will behave might not be enough to be sure we know what it is.

___

The theory tells us how to model the behaviour of systems, not how to read its mathematical structures as a literal inventory of what exists.

___

Therefore, we should accept that general relativity is a theory of extraordinary mathematical sophistication. It represents gravitation not as a force acting through space, but as the geometry of spacetime itself. Within this framework, it is natural to say that a rotating black hole “drags spacetime” around with it. The equations specify exactly how this effect should arise and what observational signatures it should produce. When those signatures are observed, our confidence in the theory’s predictive power understandably increases. A sure win for the theory.

What does not automatically follow is that spacetime is therefore a physical entity that literally undergoes dragging in the way a fluid might be stirred. That inference moves too quickly from successful calculation to metaphysical conclusion. The theory tells us how to model the behaviour of systems, not how to read its mathematical structures as a literal inventory of what exists. There are those structural realists who do make a compelling case for this view but we can entertain that this might not be compelling enough.

This gap between prediction and ontology is not unique to general relativity. On the contrary, it is characteristic of many of the most successful theories in the history of physics, and recognising this helps to put the black hole result in a broader intellectual context.

Newtonian gravity provides a clear example. For over two centuries it delivered extraordinarily accurate predictions about planetary motion, tides, and celestial mechanics. Yet it did so by invoking action at a distance, a notion that Newton himself regarded as deeply troubling. The theory worked spectacularly well, but it was far from clear what, if anything, it told us about the underlying mechanism of gravitation. The predictive success of Newtonian gravity did not settle the question of ontology. It told us how gravity behaved, not what it was, which is precisely why a deeper theoretical rethinking eventually became necessary.

Quantum mechanics offers an even starker case. Few theories have matched its predictive accuracy, and none has generated so many mutually incompatible interpretations. The mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics, often accompanied by the instruction to “shut up and calculate”, allows physicists to make astonishingly precise predictions. But it leaves open what those calculations mean, whether the world is indeterministic, whether wavefunctions are real, and how measurement outcomes should be interpreted. Here, predictive success dramatically outpaces ontological agreement.

In these cases, explanation takes a thinner and more abstract form than we might initially expect. The theory explains by showing how diverse phenomena fit within a unified mathematical structure and by enabling reliable inference, rather than by providing a transparent picture of what the world is ultimately made of.

The case of frame dragging fits this pattern exactly. General relativity explains the phenomenon by embedding it within a geometric framework that relates mass, motion, and spacetime curvature. That explanation is powerful and unifying, but it does not settle how literally we should take that geometry, whether spacetime should be understood as a physical thing in its own right, or as part of a model that earns its authority by predicting what we observe.

SUGGESTED VIEWING

The laws of physics are not fixed

With João Magueijo

This underdetermination is often obscured by the language we use. Phrases such as “spacetime is dragged” encourage us to treat theoretical structures as reality itself. Yet such language is metaphorical, even when the mathematics is exact. The danger lies in mistaking the success of the mathematical formalism for a direct window onto what really exists.

Idealisation sharpens this concern, a point memorably made by Nancy Cartwright in her provocatively titled book How the Laws of Physics Lie. Physical theories routinely rely on ideal conditions, from perfectly spherical cows of uniform density to massless strings and frictionless pulleys. These assumptions are not mistakes or oversights. They are deliberate simplifications that make calculation and explanation possible, even though they never literally describe the world we inhabit.

The black holes that appear in general relativity are idealised in exactly this way. They are described by exact solutions to Einstein’s equations, treated as smooth, isolated objects characterised by only a handful of parameters. Real astrophysical black holes, by contrast, exist in complex and turbulent environments, surrounded by matter, radiation, and magnetic fields. The fact that idealised models yield accurate predictions does not imply that every element of those models corresponds to something fundamental in reality.

At the same time, recognising the role of idealisation should not push us toward dismissing such theories as merely useful fictions. Anyone reading this is already benefiting from the extraordinary technological successes of quantum mechanics, a theory built on its own heavy idealisations. Even if a theory does not offer a complete or literal picture of the world, it can still work remarkably well. Idealisation limits what our theories tell us about ontology, but it does not diminish their power to predict, explain, and reshape the world.

From a philosophical perspective, this points toward a more modest understanding of what physical explanation achieves. In contemporary physics, explanation often consists in constructing models that capture patterns in phenomena and allow us to navigate those patterns successfully. Ontological conclusions require further argument and are rarely forced on us by empirical results alone.

This is where instrumentalism enters the picture. The instrumentalist, like Bas van Fraassen, hold that the primary virtue of a theory lies in its usefulness rather than in its truth as a literal description of reality. While few physicists or philosophers endorse a crude instrumentalism in which theories are nothing more than calculating devices, many of our most successful theories invite a more restrained attitude toward ontology. They work extraordinarily well, even when we remain uncertain about what, if anything, their central entities refer to.

SUGGESTED READING

Hawking radiation and the messy truth behind black hole physics

By Eugene Chua

General relativity may ultimately fall into this category. There is already reason to think that spacetime, as described by the theory, may not be fundamental. Many approaches to quantum gravity suggest that spacetime geometry emerges from deeper, non-spatiotemporal structures. If that is right, then spacetime dragging may be a real and robust phenomenon at one level of description without corresponding to a fundamental ontological fact about the universe.

It is, in this sense, another genuine success for the physics community. The result reflects decades of theoretical development, observational ingenuity, and collective effort, and it further reinforces the reliability of some of our most sophisticated mathematical models of the universe. It is therefore understandable that the discovery has been widely celebrated as yet another vindication of Einstein’s theory.

The philosophical significance of the result, however, is less straightforward than the headlines suggest. The central question it raises is not whether general relativity works, but what its success actually tells us. Put simply, the question is whether getting predictions right also tells us what the world is really made of. This distinction between ontological insight into what things actually exist and predictive utility, the predictive usefulness, of a theory is not a peripheral issue, it lies at the heart of how explanation operates in modern physics.

___

Prediction can outrun ontology and still justify belief.

___

Seen in this light, the recent observations are not metaphysically decisive. They strengthen our confidence in general relativity as an extraordinarily reliable framework for prediction and unification, but they do not settle the question of what spacetime really is. Expecting them to do so may reflect a misunderstanding of what scientific theories are capable of delivering.

If we want to understand what it means for spacetime to be, the most defensible guide is not radical scepticism, nor a demand for ontological certainty that floats free of scientific practice, but a modest naturalism grounded in our best theories. Naturalism of this kind does not promise final answers. It treats ontology as something to be inferred cautiously from successful scientific frameworks, always provisionally and always open to revision. On this view, what exists is revealed to us through the structures that allow us to explain, predict, and intervene in the world, even when those structures are idealised and abstract.

This stance will not satisfy some curmudgeonly philosophers who insist that genuine understanding requires more than predictive success, or that ontology must be secured independently of scientific modelling. But that dissatisfaction reflects a deeper tension between philosophical scepticism and the actual achievements of science. Physics has never offered a view from nowhere. What it offers instead is something more modest and more powerful: a disciplined way of discovering how the world behaves, and a continually improving guide to what we have reason to take seriously as real.

The black hole result should therefore not be read as a final revelation of spacetime’s nature, but as another reminder of how scientific knowledge advances. Prediction can outrun ontology and still justify belief. If we want to understand spacetime, we will not do better by stepping outside science, but by taking seriously what our best scientific practices commit us to, while remaining honest about their limits.