A giant star in the Andromeda Galaxy has vanished without a trace, leaving scientists puzzled and intrigued. First observed brightening in 2014, the yellow supergiant M31-2014-DS1 faded out of view by 2018, without showing any signs of a supernova explosion. Now, two new studies are offering competing explanations for what might have happened to the missing star.

The mysterious disappearance of M31-2014-DS1 challenges long-held assumptions about how massive stars end their lives. Usually, stars of its size explode in a final burst of energy before collapsing into either a black hole or a neutron star. But in this case, there was no such spectacle, just an object that grew brighter for a time and then slowly faded from sight.

Possible Case Of A Failed Supernova

One leading explanation comes from a team that analyzed data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and Chandra X-ray Observatory. According to the arXiv preprint server, the first paper is posted on arXiv, and the second paper is also posted there, the star may have undergone a failed supernova, a direct collapse into a black hole without the typical explosion. The researchers observed a faint, extremely red source at the position where M31-2014-DS1 was last seen. This object is now only 7 to 8 percent as bright as the original star and is surrounded by a large shell of dust measuring 40 to 200 astronomical units across.

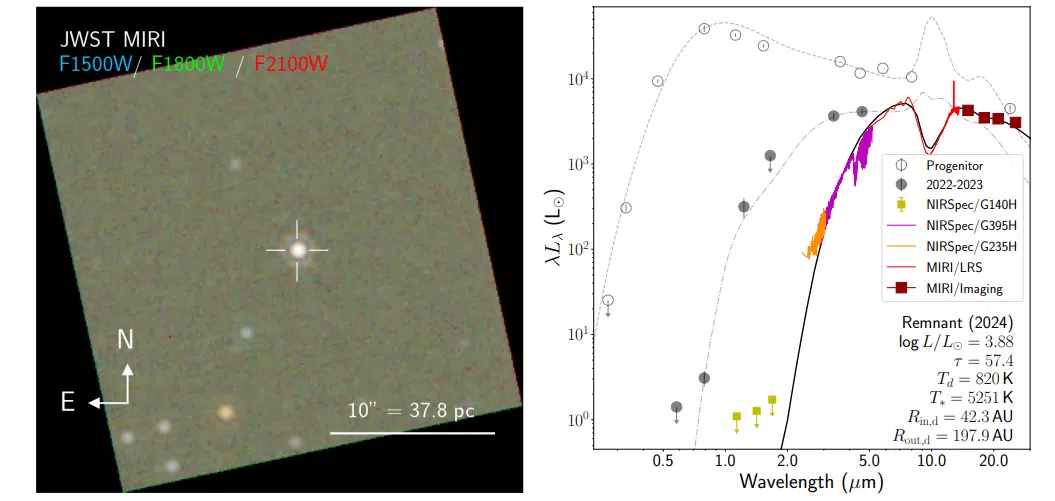

(Left) A color JWST image of M31-2014-DS1, with its position marked. (Right) How its light changed over time. Credit: arXiv

(Left) A color JWST image of M31-2014-DS1, with its position marked. (Right) How its light changed over time. Credit: arXiv

The team proposes that the dust and faint infrared glow could come from fallback material, gas ejected during the collapse that later falls back into the newly formed black hole. As they noted in their preprint:

“The accretion luminosity is not detected in X-ray observations to ~100 times deeper limits than the IR luminosity,” suggesting the surrounding dust might be absorbing the X-rays, making them undetectable from Earth.

This idea aligns with the possibility that the thick dust envelope is obscuring the high-energy emissions typically associated with black hole formation.

X-ray Silence Casts Doubt

Despite this detailed interpretation, a second team has challenged the failed supernova theory. According to their analysis, multiple sets of X-ray data gathered from Chandra (2015 and 2024) and Swift (2020) show no sign of X-ray activity at the location of the missing star. This contradicts what one would expect from fallback accretion onto a black hole, which should generate long-lasting X-ray emissions, potentially for thousands of years.

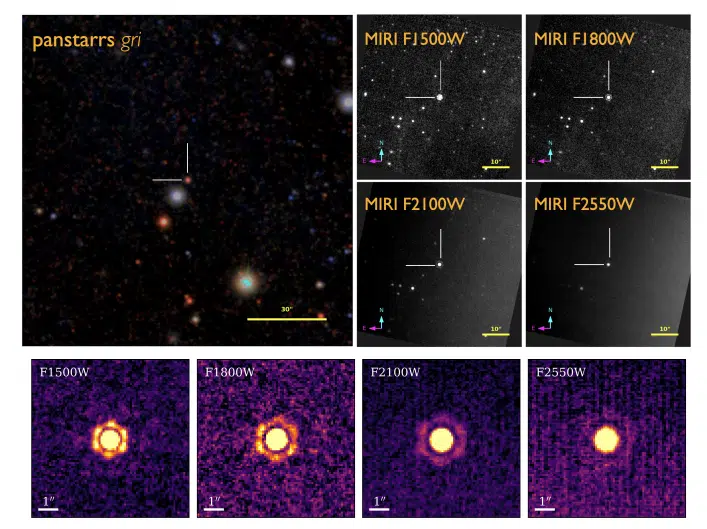

Top left: Where M31-2014-DS1 is located. Top right: A JWST image of the same spot. Bottom: How the telescope sees the object in different filters. Credit: arXiv.

Top left: Where M31-2014-DS1 is located. Top right: A JWST image of the same spot. Bottom: How the telescope sees the object in different filters. Credit: arXiv.

The researchers also point out that the faint red source left behind has not significantly faded over time. In a typical failed supernova scenario, accretion luminosity would be expected to decline, matching the diminishing fallback of material. The consistent brightness observed complicates the model. As the second team wrote:

“Several observational details challenge the interpretation of M31-2014-DS1 as a failed SN.”

A Star Being “fed” By A Companion

Given these contradictions, the second group of scientists suggests another possible cause: a stellar merger. They argue that the faint red object and the heavy dust shell might not be the result of a collapse but rather of two stars colliding, forming a new object enshrouded in a thick cloud of dust. This would account for the increased brightness observed in 2014, followed by gradual fading as the dust expanded.

The idea of a merger also explains the lack of X-ray emissions and the relatively stable infrared signature, as no accretion onto a black hole would be taking place. According to their interpretation, the system might eventually brighten again as the dust dissipates, allowing clearer observation of the central source. As both teams note, distinguishing between a merger and a failed supernova will require further monitoring in the coming years, particularly with JWST.