When the stories of art are told, it is usually the artist’s name that shines. We speak of Picasso and Kahlo, Warhol and Kusama, Rothko and O’Keeffe. Their signatures, their faces, their mythologies dominate the canon. Yet hidden behind those luminous names is another figure whose hand has guided the trajectory of art as much as the brush of the painter or the chisel of the sculptor. The curator is rarely remembered in everyday conversation, rarely cited in coffee-table books or school textbooks, yet the profession has shaped the very way art is seen, understood and valued. Without curators, much of the art that now defines our cultural imagination would have remained silent or invisible, confined to studios and storerooms. The curator, in a sense, is the invisible architect of art’s public life.

Craft of care, context

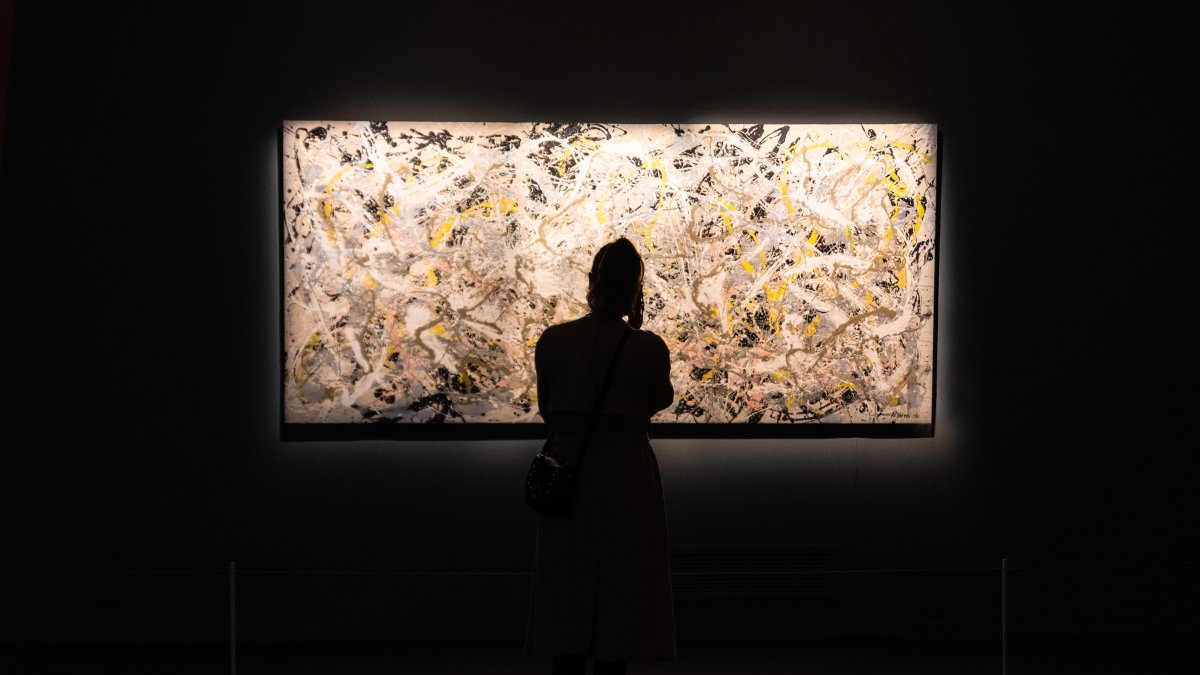

The word itself comes from the Latin curare, meaning “to care for.” This act of care is both literal and metaphorical. Curators care for collections, of course, ensuring that works survive time and circumstance. But they also care for meaning. They interpret, they frame, they arrange. A painting on a wall is not neutral. Where it hangs, what it hangs beside, how it is lit, what the wall text says and how the viewer is invited to engage with it. All of this is the curator’s domain. They are the storytellers of space, shaping the narrative that turns a group of works into a coherent statement, a single exhibition into a cultural moment. In this sense, they are as much authors as caretakers, writing in the medium of juxtaposition and context rather than ink.

For artists, curators can be translators. The artist speaks in the raw language of image and material, but the curator translates those gestures into something the public can grasp. A strong curatorial frame can elevate an artist’s work into a global statement, while a careless one can suffocate even the most brilliant vision. Jean-Michel Basquiat might have remained a graffiti voice in downtown New York if curators and gallerists had not recognized his paintings as urgent commentaries on race, jazz and the fractured landscape of the 1980s. Marcel Duchamp’s infamous “Fountain,” a urinal submitted as sculpture in 1917, was initially dismissed, but it was later curators and historians who reframed it as a radical act that shattered conventional aesthetics and birthed conceptual art. In these cases, the artist provided the spark, but the curator kept the fire alive, ensuring it did not flicker into obscurity.

The 20th century brought the rise of the independent curator, a figure no longer tied exclusively to museum collections but to ideas. Perhaps no name is more emblematic than Harald Szeemann. His 1969 exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form at the Kunsthalle Bern” was a seismic event. He brought together conceptual and process-based art, installing works not as finished objects but as open gestures, plaster splattered on floors, wax melting in corners, live actions unfolding before visitors. The show scandalized traditionalists, but it also announced a new era where the curator was not merely arranging but authoring exhibitions as works in themselves. Szeemann’s later direction of “Documenta 5” in 1972 further cemented this role. He framed the exhibition as a “museum of 100 days,” presenting art not as isolated works but as phenomena interwoven with politics, media and everyday life. Artists such as Joseph Beuys and Nam June Paik found their radical gestures legitimized through his vision. Without his curatorial daring, many of these names might have remained on the periphery of European art history.

In the early 2000s, Okwui Enwezor took this curatorial authorship to another level. His “Documenta 11” in 2002 broke the Eurocentric mold of global exhibitions, staging platforms in Lagos, New Delhi, St. Lucia and Vienna. For the first time, a major art event treated African, Asian, Caribbean and post-colonial voices not as exotic appendices but as central participants. Enwezor reframed the geography of art and artists from El Anatsui to Yinka Shonibare, from Isaac Julien to Shirin Neshat and gained international visibility through his daring lens. The reverberations of that Documenta still echo today, as museums grapple with decolonization and representation. Here again, the curator was not only a mediator but a game-changer, shifting the balance of cultural power.

One cannot speak of curators without mentioning Hans Ulrich Obrist, often described as the most connected man in the art world. Since the 1990s, he has staged countless exhibitions, interviews and dialogues that collapse the boundaries between disciplines. His “Do It” project, launched in 1993, invited artists to submit instructions for works that could be enacted anywhere, by anyone. It was an exhibition as an open score, endlessly reproducible and participatory. Obrist’s role has been less about monumental shows and more about weaving a continuous global conversation, ensuring that art remains a living dialogue rather than a frozen object. Artists such as Philippe Parreno and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster grew within this context of experimentation, their works inseparable from the curatorial frameworks that nurtured them.

But long before the professionalization of curating, some figures acted as proto-curators, shaping modern art through their vision and daring. Peggy Guggenheim was not a curator in the strict sense but a collector who curated with instinct. Her gallery, Art of This Century, in New York in the 1940s, was more than a commercial space; it was a curatorial experiment in itself. She gave Jackson Pollock his first solo show, placing his drip paintings within a radical display of curved walls and theatrical lighting designed by Frederick Kiesler. The environment amplified Pollock’s energy, convincing critics that something new had arrived. It is not an exaggeration to say that without Guggenheim’s curatorial daring, Pollock might never have become the emblem of Abstract Expressionism and New York might not have supplanted Paris as the art capital of the postwar world.

Heiress Peggy Guggenheim wears a large brimmed hat, aboard the Atlantic Clipper, as she arrives in New York City from France. (Getty Images)

The Venice Biennale offers countless examples of curatorial impact. Every national pavilion is, in essence, a curatorial statement: a country deciding how it wishes to present itself through art. When Massimiliano Gioni curated the main exhibition in 2013 under the title “The Encyclopedic Palace,” he filled the halls with outsider art, visionary drawings and works by self-taught creators alongside contemporary giants. The effect was to blur the boundaries between professional and amateur, between canon and margin. Suddenly, the art world was speaking of spiritual diagrams and eccentric cosmologies with the same reverence as market-driven stars. That shift of attention was not accidental; it was the power of curatorial framing to expand the definition of art.

Behind every powerful exhibition is a set of invisible decisions that can make or break an artist’s voice. The lighting that highlights a brushstroke, the juxtaposition that sparks a dialogue, the pacing that allows viewers to breathe between intensities – these are not neutral acts. They are curatorial gestures that shape memory. Visitors often remember an exhibition as a whole experience rather than as discrete works. The “blockbuster” shows of recent decades – from “Sensation” in London in 1997 to “China: Through the Looking Glass” at the Metropolitan Museum in 2015 – were as much triumphs of curatorial spectacle as of artistic production. Damien Hirst’s shark in formaldehyde became iconic partly because of the way it was staged in “Sensation,” a show orchestrated by the young curator Norman Rosenthal and the Saatchi collection. Without that frame, it might have remained a shocking but isolated object.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist attends the Serpentine Summer Party 2025 at Serpentine South Gallery, London, U.K., June 24, 2025. (Getty Images)

Curator as cultural diplomat

Curators also serve as cultural diplomats. They bridge audiences with worlds they might otherwise never encounter. When exhibitions of Islamic calligraphy or African masks entered Western museums in the early 20th century, they were often framed exotically, sometimes problematically. But contemporary curators strive to correct this, to present these works not as ethnographic curiosities but as integral parts of global modernity. The late Salah Hassan, among others, curated shows that placed African modernism alongside European avant-gardes, insisting on a more nuanced narrative. Such reframing not only affects how we see objects but also how entire cultures are positioned within the story of art.

Of course, curators are not immune to criticism. Some are accused of overshadowing artists, turning exhibitions into showcases of their own intellectual ego. The term “curator as auteur” has been debated for decades. Is the exhibition an artwork in itself, authored by the curator, or should it remain a neutral vessel for artists’ voices? The answer, perhaps, lies in balance. The greatest curators are those whose vision amplifies rather than eclipses, who create conditions where artists can resonate most fully. The worst are those who impose rigid frameworks that flatten diversity into a singular argument. Yet even in controversy, the curator remains indispensable. The debates themselves prove that curating is not a secondary act but a central component of cultural production.

Anecdotes abound that illustrate the curatorial touch. When the young curator Walter Hopps staged a show for Marcel Duchamp in Pasadena in 1963, the French artist was amused to find a museum in California so eager to honor him. The retrospective reintroduced Duchamp to a new generation, cementing his influence on American conceptualists. Hopps later gave Andy Warhol his first major museum exhibition, recognizing that the silkscreened Marilyns and soup cans, far from trivial, were capturing the pulse of American life. In both cases, Hopps was not merely arranging works but sensing a cultural moment and giving it form.

Today, the role of the curator continues to expand. They are mediators in a global art economy, negotiators between artists, institutions, collectors and audiences. They address not only aesthetics but politics, ecology and technology. When Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev curated “Documenta 13” in 2012, she included scientists, philosophers and even a dog named “The Brain” in her roster, insisting that art could not be separated from other forms of knowledge. The result was sprawling, chaotic, but unforgettable, pushing the very definition of what an exhibition could be.

The power of curators is perhaps best seen in the careers of artists who, without the right framing, might have vanished. Think of Felix Gonzalez-Torres, whose piles of candy and strings of light bulbs became emblems of intimacy and loss in the era of AIDS. It was curators like Nancy Spector and Ann Goldstein who placed his fragile works in contexts that emphasized both their political urgency and poetic delicacy. Or consider Cindy Sherman: her “Untitled Film Stills” might have remained personal experiments had curators not recognized them as searing commentaries on gender and image, positioning them within feminist discourse. The artists provided the material, but the curators gave it resonance.

To speak of curators as hidden heroes is not to diminish the artist but to recognize the ecology of art. No one creates in isolation. The studio may be solitary, but art becomes public through networks and curators are the nodal points in those networks. They are editors of culture, archivists of the present, narrators of possible futures. Their names may not be as famous as those of the artists they champion, but their fingerprints are everywhere – on the way we walk through museums, on the way we remember exhibitions, on the way art history itself is written.

The next time we marvel at a masterpiece in a perfectly lit gallery, or find ourselves moved by the unexpected juxtaposition of two works that seem to speak across centuries, or leave an exhibition with our worldview shifted, we might pause to consider the invisible hand that made it possible. The curator is not the artist, but without the curator, the artist might never reach us in the same way. They are the invisible architects of art, the hidden heroes of exhibitions, the ones who care, frame and connect. Their work may remain in the background, but its effects shape the very foreground of our cultural lives.