Wild dolphins are putting sea sponges over their snouts to hunt along the seafloor, and the tool changes what they can sense.

That choice matters because it shows how animal traditions survive only when brains can adapt to the hidden costs.

In Shark Bay, Western Australia, some bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops aduncus, have been filmed grabbing marine sponges and covering their beaks.

The work was led by Ellen Rose Jacobs, Ph.D., at Aarhus University, where she studies dolphin behavior and sound.

Jacobs teamed with the Shark Bay Dolphin Research Project at Georgetown University, which has tracked these dolphins since 1984.

By following the sponges from seafloor to snout, the researchers aimed to learn what the tool saves, and what it costs.

Shielding from rocks

During these hunts, the sponge shields delicate skin from sharp rocks and stinging animals hiding in the sand.

At the same time, the sponge bends click sounds for echolocation, finding prey by listening to echoes, and the signal arrives warped.

In a detailed report, Jacobs described the sponge as changing sound cues while the dolphin searches for fish.

“Everything looks a little bit weird, but you can still learn how to compensate,” said the team lead during fieldwork in Shark Bay.

Clicks, echoes, and jawbones

Click sounds used in dolphin language pass through the melon, a fatty organ that focuses sound forward, before spreading into the water.

Echoes return through the lower jaw, where fat-filled tissues carry vibrations toward the middle and inner ear.

When a sponge covers the snout, some of that outgoing beam and incoming echo must pass through sponge tissue twice.

That extra layer can scatter energy and smear timing, which forces the brain to work harder before the chase begins.

Analyzing dolphin sponge behavior

To test whether dolphins kept clicking with a sponge on, Jacobs listened underwater as they worked the channel bottoms.

Jacobs’ recordings showed active clicks, and the AU team used a physics-based computer analysis to trace those sound changes.

By scanning real sponges and building digital shapes, the team followed a click from emission to the returning echo.

The results pointed to constant variation because each sponge has its own shape, so learners face new problems each hour.

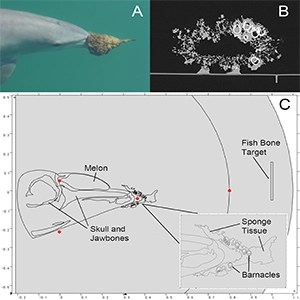

Sponging dolphin and model set-up. (A) A dolphin sponge foraging using an Echinodictyum sponge. Photo taken by Ewa Krzyszczyk with the Shark Bay Dolphin Research Project. (B) A cross-section of the Echinodictyum sponge used in the model. (C) The full model set-up in COMSOL. Credit: Royal Society Open Science. Click image to enlarge.Shape matters more than size

Sponging dolphin and model set-up. (A) A dolphin sponge foraging using an Echinodictyum sponge. Photo taken by Ewa Krzyszczyk with the Shark Bay Dolphin Research Project. (B) A cross-section of the Echinodictyum sponge used in the model. (C) The full model set-up in COMSOL. Credit: Royal Society Open Science. Click image to enlarge.Shape matters more than size

Different sponge shapes produced different sound outcomes, even when dolphins used similar hunting moves in the same habitat.

Cone-like sponges such as Echinodictyum mesenterinum guided the outgoing click, while basket-like Ircinia sponges tended to spread it wider.

The wider beam also reached the jaw with less strength in the simulations, so the echo arrived weaker and longer.

Because dolphins pick up fresh sponges often, small differences in shape could decide whether the tool feels usable.

Learning takes years, not days

Only about 5% of the dolphins observed in this population kept using sponges, even though many neighbors saw them hunt.

Young dolphins stayed close to their mothers for around three to four years, and that long attention built muscle memory.

Because calves watched the same technique thousands of times, most learning happened inside those family bonds, not in wider groups.

Limited access to practice kept most dolphins from training long enough to get past the sensory confusion.

Why the benefit stays high

Once a dolphin mastered the move, the sponge let it probe sandy channels and flush fish hiding under rubble.

The dolphin pushed the covered beak through the bottom, stirred up barred sandperch, then dropped the sponge to chase. Wild sponges ranged from softball size to a cantaloupe, so the tool also had to fit the hunt.

Because the payoff was food that other dolphins missed, a few specialists kept investing in the harder technique.

Culture with hard limits

Tool use can spread fast in animals when it adds value without disrupting other skills, but sponging carries a penalty.

While tools often help animals get food or avoid harm, scientists have paid far less attention to the hidden difficulties that can prevent those tools from spreading through a population.

The team linked that penalty to a slow learning curve, even when the hunting payoff stayed high.

That kind of trade-off helped explain why dolphins living beside spongers did not copy them, despite frequent contact.

Learning from dolphins and sponges

Sound is the main way these dolphins sense distance and shape underwater, and sponging shows how fragile that channel can be.

When boat engines and other human noise raise background levels, important clicks and echoes can be masked before they reach the ear.

A sponge adds its own distortion, so any extra masking from the environment could make the hardest hunts even harder.

Protecting quiet foraging areas therefore mattered, especially in places where dolphins already depended on sound to succeed.

Across protection, perception, and learning, sponge hunting showed how a simple tool can shape a whole family tradition.

Future work can test how dolphins choose sponges and how changing soundscapes might change which specialists succeed.

The study is published in Royal Society Open Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–