Even with persistent errors, today’s quantum machines have reproduced the defining signatures of chaotic behavior at scales once considered unreachable.

That result reshapes what imperfect hardware can credibly reveal about complex physical systems while more robust machines remain on the horizon.

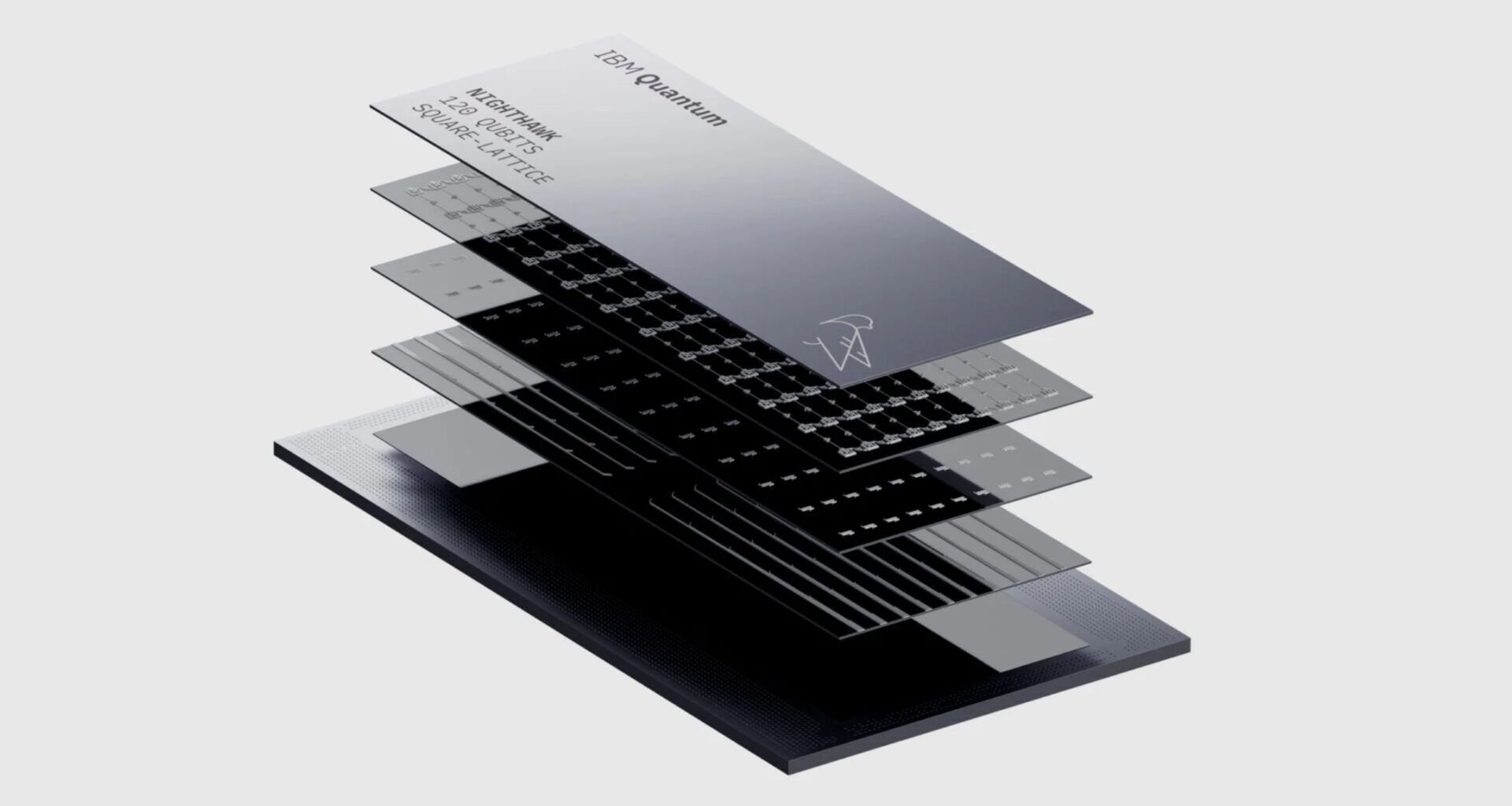

On a 91-qubit superconducting processor at IBM Research, the team documented these patterns across large, interacting quantum systems.

Laurin E. Fischer at IBM Research Europe, Zurich, led the effort that established this agreement under real operating conditions.

That approach matters because trust, not speed, decides when quantum computers move from demos into tools that scientists can lean on.

Quantum chaos as a benchmark

Using a superconducting processor, the team simulated quantum chaos, rapid mixing that erases local signals, across 51 to 91 qubits.

Chaos in large, interacting systems makes errors spread, so classical checks become expensive as the circuit grows.

To stress the hardware, the runs used 4,095 two-qubit gates, long enough for noise to hide inside the physics.

If those patterns match theory anyway, scientists gain a way to judge which quantum results deserve serious attention.

Controlled chaos in circuits

Designers picked dual-unitary circuits to create chaos while preserving built-in reversibility in time and space, which leaves a few checks.

Earlier work showed that these circuits let physicists compute certain local correlations exactly, even when the dynamics stay complex.

That narrow window of exact answers provides a reference, letting researchers compare noisy measurements to a target curve without guesswork.

Without those built-in checks, a successful run could still be a lucky match between errors and expectations.

A signal that should fade

The main test tracked an autocorrelation function, a measure of how much a disturbance resembles itself later.

In the model, the function decays as information spreads, which signals that the system forgets where it started.

Exact theory predicted a simple exponential drop for several settings, so the team had a clear line to aim for.

Because the quantity is local, it can flag trouble early, before errors build up into a completely misleading picture.

Quantum error correction

Uncorrected measurements faded too quickly, so the group relied on error mitigation, software steps that estimate noise-free answers after runs.

They first learned how two-qubit gate layers distort results, then used classical post-processing to undo much of that bias.

The corrected curve matched theory for gates beyond the easiest-to-simulate set, which made the benchmark closer to real research.

A key review explained why full quantum error correction, checks that fix errors mid-run, needs far more qubits than current hardware offers.

Tensor methods explained

To scale error mitigation, the researchers used tensor networks, math structures that compress huge calculations into linked smaller pieces.

The method built an approximate inverse noise map and applied it after the circuit finished, not during execution.

Their Tensor-network Error Mitigation (TEM) approach learned the noise from calibration runs and corrected the final observable.

Because TEM depends on a stable noise model, hardware drift can reduce accuracy and leave residual bias.

Testing competing models

After passing exact checks, the researchers pushed the circuit away from the dual-unitary setting, where no closed-form answers exist.

They compared the quantum outcomes to two classical tensor-network simulations, one tracking evolving states and one tracking evolving operators.

Those classical methods disagreed, yet the TEM-mitigated hardware data stayed closer to the operator-tracking approach across tested settings.

In that role, the quantum processor acted as a referee, offering evidence when classical approximations pointed in different directions.

Speed makes mitigation practical

Practical experiments also need pace, and the full workflow for the largest runs finished in just over three hours.

Fast sampling, above 1,000 measurements per second, lets the team gather large data sets without stretching the machine over days.

That turnaround mattered because mitigation needs repeated noise characterization, and short cycles help catch drift before it corrupts later results.

The trade is extra classical computing, which may limit what smaller labs can do without shared cloud resources.

Validated chaotic simulations can serve as benchmarks, giving hardware teams a target and theorists a new way to test ideas.

A report framed progress as a mix of hardware, software, and error handling, not as a single, simple fix.

“There are many pillars to bringing truly useful quantum computing to the world,” said Jay Gambetta, Director of IBM Research.

Until fault-tolerant machines arrive, validated simulations could support materials, drug discovery, traffic flow, and logistics planning.

What reliability unlocks

The results show that careful benchmarking plus post-processing can turn noisy quantum hardware into a tool for studying chaos.

Researchers will need broader measurements and longer circuits, because mitigation accuracy can drop as noise changes over time.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–