Astronomers have long faced a strange contradiction: most stars are born in pairs, and most stars have planets, so logically, planets orbiting two stars at once should be common. However, in reality, planets orbiting binary stars are surprisingly rare.

When scientists counted such planets, the numbers shocked them. Out of more than 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, only 14 orbit binary star systems. This mystery has lasted for more than a decade, and neither planet formation theories nor telescope limits could explain it.

Now, a new study reveals why. Their work suggests that many of these planets do form, but are later destroyed or expelled as the two stars slowly change their orbits. This effect is driven by Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

How shrinking star pairs quietly destroy their planets

The researchers focused on tight binary stars, pairs of stars that orbit each other very closely, often completing an orbit in less than seven days. These systems are especially important because NASA’s Kepler and TESS missions observed thousands of them.

“You have a scarcity of circumbinary planets in general, and you have an absolute desert around binaries with orbital periods of seven days or less,” Mohammad Farhat, first author of the study and a postdoc researcher at UC Berkeley, said.

Kepler alone identified around 3,000 eclipsing binaries, where the stars regularly pass in front of each other from our point of view.

Since about 10 percent of single stars host large planets, astronomers expected to find roughly 300 circumbinary planets. Instead, only 47 candidates appeared, and just 14 were confirmed. To understand this big difference, the study authors examined how orbits change over time.

When gravity falls out of sync

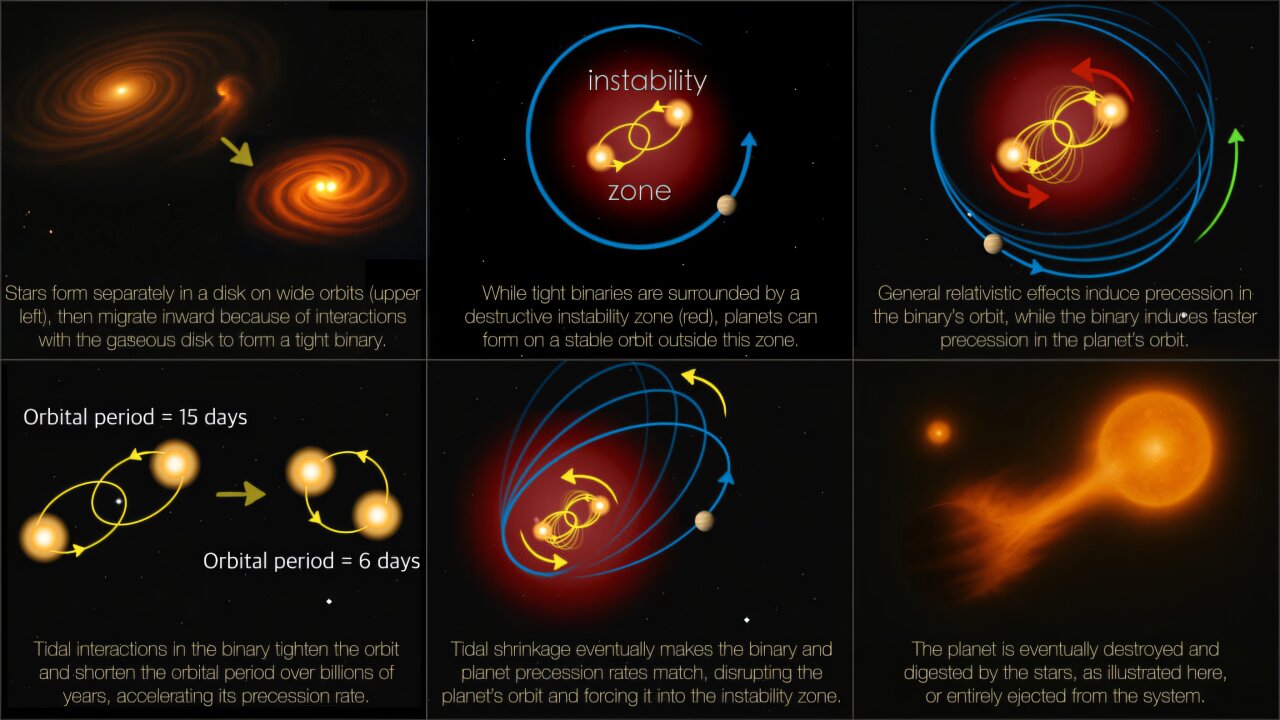

This is how planets vanish from a binary star system. Source: Mohammad Farhat/UC Berkeley

This is how planets vanish from a binary star system. Source: Mohammad Farhat/UC Berkeley

In a binary system, the two stars usually differ slightly in mass and move along stretched, elliptical paths. A planet circling both stars feels constantly shifting gravitational pulls, causing its orbit to slowly rotate in space—a motion known as precession. This effect follows standard Newtonian gravity.

However, the stars themselves also experience orbital precession, and this is driven mainly by general relativity once the stars are close enough. As binary stars age, tidal forces and interactions with surrounding material cause them to spiral inward over millions to billions of years.

As their orbit tightens, the relativistic precession of the stars speeds up, while the planet’s precession slows down, because the stars act more like a single object from far away.

At a critical point, the two precession rates lock together. This resonance dramatically stretches the planet’s orbit, turning it into a long, narrow ellipse. During each pass, the planet dives closer to the stars until it crosses into a dynamically unstable region where three-body gravity becomes chaotic.

At this point, “two things can happen: Either the planet gets very, very close to the binary, suffering tidal disruption or being engulfed by one of the stars, or its orbit gets significantly perturbed by the binary to be eventually ejected from the system. In both cases, you get rid of the planet,” Farhat added.

Computer models show that this process eliminates around 80% of planets orbiting tight binaries, and most of those are physically destroyed, not merely displaced. Crucially, this explains why the few surviving circumbinary planets are found just beyond the instability boundary—close enough to detect, but far enough to avoid catastrophe.

Relativity continues to matter

This research suggests that the universe may not lack planets around binary stars—it actively removes them. Many such planets may still exist, but only at wide distances where current detection methods struggle to see them.

“There are surely planets out there. It’s just that they are difficult to detect with current instruments,” Jihad Touma, one of the study authors and a physics professor at the American University of Beirut, said.

The findings also expand the role of general relativity beyond extreme environments. Nearly a hundred years after relativity solved the mystery of Mercury’s orbit, it is once again changing how astronomers understand planetary motion—this time by explaining why some worlds never survive long enough to be seen.

The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.