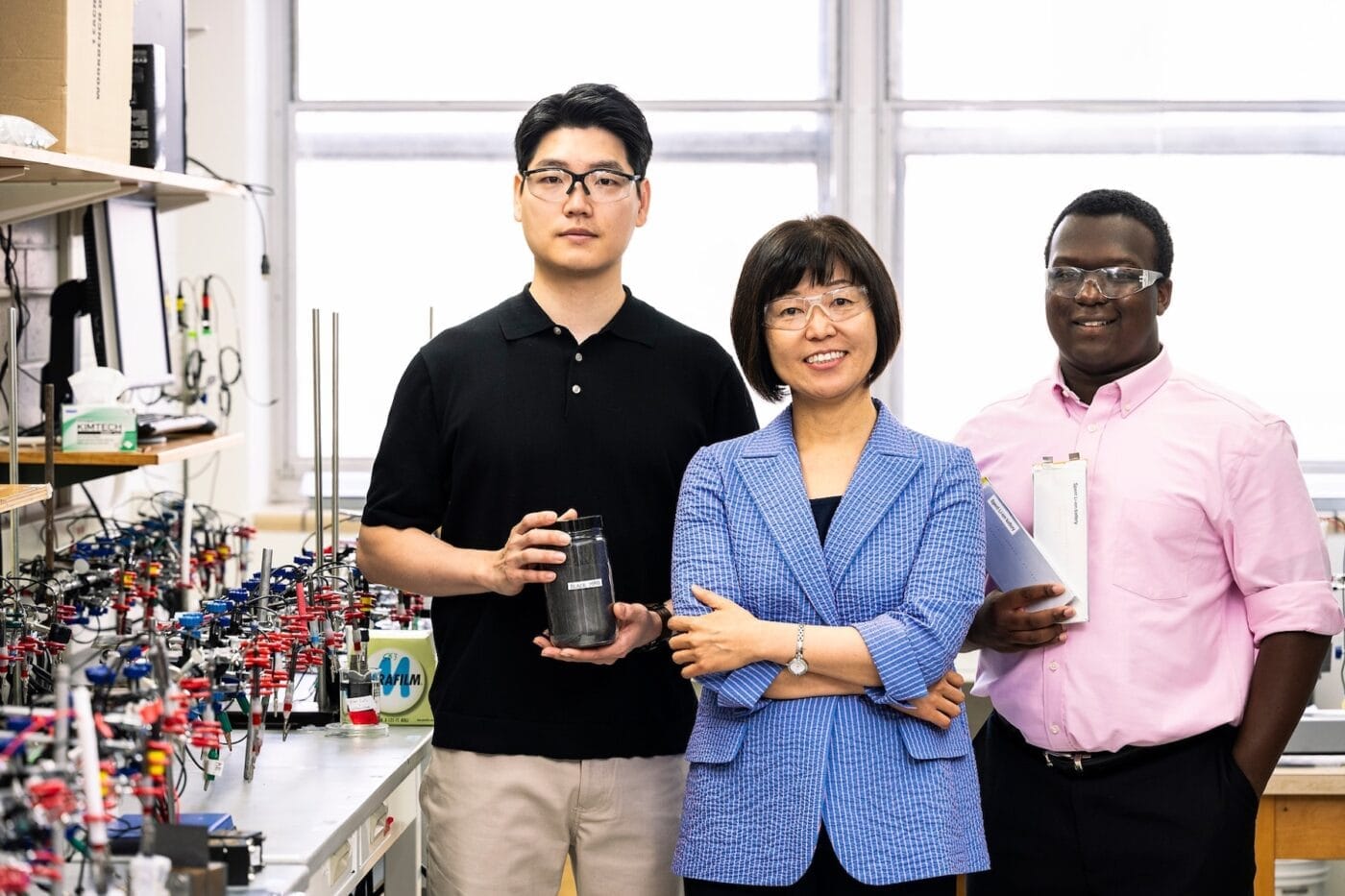

The team led by chemistry professor Kyoung-Shin Choi focused specifically on recycling LFP batteries, or lithium iron phosphate cells. Recycling these has so far been complex and costly, and only a few companies are active in this field. British startup Altilium began recycling LFP batteries last winter, while German startup Cylib plans to launch large-scale operations in 2026.

Recycling LFP batteries has generally been seen as less attractive than recycling NMC batteries. Unlike NMC batteries, they contain no nickel, cobalt or manganese, but instead iron and phosphorus, giving them a lower raw material value. The lithium content in LFP batteries is also lower than in NMC cells, further weakening the business case for recycling.

Recycling instead of mining and brine extraction

According to researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, existing methods for recovering lithium from LFP batteries are too complex and therefore too expensive. “At this point, there’s no economically compelling method to recover lithium from spent LFP batteries even though the market is shifting to them,” said Kyoung-Shin Choi.

Recycling, however, is desirable, as conventional lithium extraction from mines and brine deposits has significant environmental impacts, even if it is sometimes cheaper than recycling. It also increases dependence on lithium-exporting countries, particularly China, creating a geopolitical risk.

Choi’s team has developed a simple electrochemical process that can recover lithium more cheaply than conventional hydrometallurgical methods, which use acids and bases. The new process extracts lithium ions from used batteries and recovers them in nearly pure form – without the energy-intensive heat used in pyrometallurgy for NMC batteries, or the lengthy chemical processes that consume large amounts of reagents and generate waste.

Specifically, lithium ions are first extracted from old batteries and selectively captured by a lithium-ion storage electrode. In a second step, the stored lithium ions are released into a separate solution to be recovered as high-purity lithium chemicals.

Spin-off to drive technology forward

Choi and her team have already tested the process successfully on old LFP cells as well as so-called black mass, the ground material from spent batteries. The process is patented, and a spin-off company is planned to bring the technology to market. “The technology works, but it is important to scale it up in the most cost-effective manner,” said Choi. According to the researcher, the work has already attracted interest from several battery and automotive manufacturers. The project also receives support from Samsung.

The idea comes at the right time. From 2031, the EU will require new batteries to contain at least six per cent recycled lithium, rising to twelve per cent by 2036. For battery makers and car manufacturers, the issue is pressing – lithium is needed for today’s common NMC batteries as well as for LFP cells, which BMW, Mercedes and Volkswagen also plan to adopt.

This article was first published by Florian Treiß for electrive’s German edition.