When does a metronome become a work of art? When you add a paper cutout of an eye to its pendulum bar.

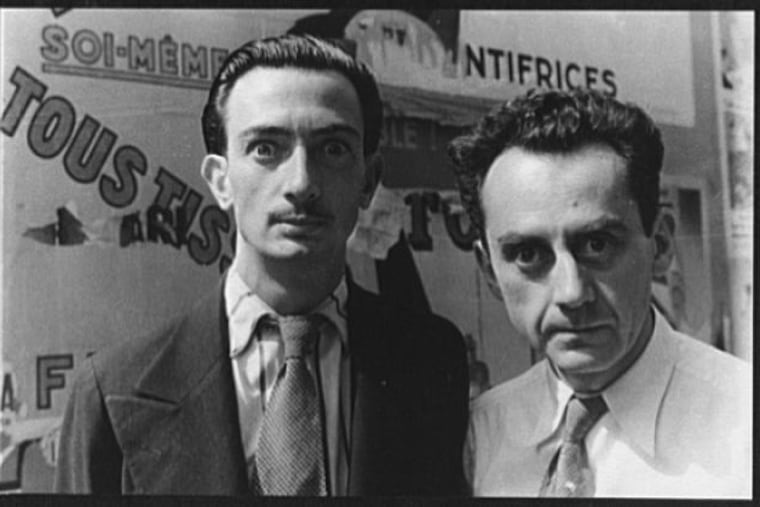

That’s what Philadelphia-born artist Man Ray decided to do in 1923; transforming an everyday commercial object into a sculpture, a “ready made piece.” It was Ray’s close friend, the provocative French artist Marcel Duchamp, who coined the phrase and popularized the medium in the 1910s to criticize the art industry through avant-garde works, like his famous urinal (Fountain).

South Philadelphia-born Ray’s sculpture was not as flashy or vulgar, but took on a mythic story of its own. Named Object to Be Destroyed, the watchful metronome ticked at a steady pace in Ray’s Parisian studio (he moved in 1921) as he painted because, he later explained, “a painter needs an audience.” Later, in a bout of creative frustration, Ray could no longer bear the surveillance, so he fulfilled the title’s promise and, in his words, “smashed it to pieces.”

It wouldn’t be the first time Ray’s metronome was destroyed. In 1957, art students took the sculpture from a gallery and reportedly shot it with a pistol. Over time, the cycle of creation and destruction became part of a larger point — that the idea of the artwork could never truly be erased. So he renamed it Indestructible Object.

A century later, that remains true: Ray’s metronome replicas appear in several collections, including in that of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which will display the artwork as part of the forthcoming exhibit, “Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100,” opening Nov. 8.

Philadelphia is the only U.S. city to host the touring show, which began in Brussels, Belgium, last year and has since stopped in Paris, Madrid, and Hamburg, Germany.

More than 60 artists are featured in the sweeping retrospective, including big names like Duchamp, Ray, Dalí, and Picasso, as well as lesser-known artists like Czech painter Toyen and Cuban artist Wifredo Lam. The Philadelphia show has a particular focus on exiled artists who fled Europe during World War II and continued to practice from Mexico, the Caribbean, and New York.

Surrealism was first articulated as an artistic and literary movement in 1924 (hence the centenary) by André Breton, who believed that imagination was essential to one’s life and liberation. Surrealist expression melds what’s real and what’s fantasy. A lobster replaces a telephone to become Dalí’s Aphrodisiac Telephone. Look closer, and a robe made of fabric looks like branches of small bodies in Dorothea Tanning’s Birthday.

Long before artificial intelligence took over our timelines with derivative digital slop, Surrealists spent hours crafting artworks of absurdity for a purpose, showcasing their most outlandish thoughts to reveal unexpected truths.

“Surrealism was not an art movement and not a movement in literature, although we think of it that way. It was a philosophy of life all about revolt against the status quo … and, at the same time, reimagining the way things might be,” said Matthew Affron, Muriel and Philip Berman curator of modern art at PMA. “It wants to make you uncomfortable in a good way, to change your frame of reference, to change your way of seeing the world and yourself, to shock you out of mental reference points.”

While Philadelphia itself was not a key site for the Surrealist movement historically, the Art Museum has become a focal point for Surrealist art collections, due in large part to former director Fiske Kimball, who beat out other museums to secure major acquisitions from Albert E. Gallatin and Louise and Walter Arensberg’s collections in the 1950s. It was the Arensbergs’ holdings that led to the Art Museum’s status today as the repository for the world’s largest collection of Duchamp works.

Kimball’s efforts were prescient, too.

“Though we think of many of the artists whose works are in the Arensberg collection as museum artists today, in 1950, it was not obvious to everyone that these would be lasting figures … not everyone agreed that they would be important forever,” said Affron.

Duchamp, everyone can agree now, became one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. So when Man Ray met him in 1915 at an artist colony in Ridgefield, N.J. (thanks to Walter Arensberg), it changed the trajectory of his life.

Ray was born in Philadelphia in 1890 with the name Emmanuel Radnitzky, the son of a tailor and a seamstress, both Jewish immigrants from Russia. According to Ray’s 1976 obituary in The Inquirer, the family lived at 418 Carpenter St. in South Philadelphia until Ray was 7 and then moved to Brooklyn.

After meeting Duchamp, Ray went on to become one of the sole Americans in the burgeoning Surrealist scene in Paris, where he pioneered a cameraless photographic technique called the Rayograph and experimented with film (his 1923 work Return to Reason will also be on view).

Some of his most recognized works depicted former lovers and muses. Ray photographed French model Alice Prin, aka Kiki de Montparnasse, in the nude to create Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), which set a record in 2022 as the most expensive photograph sold at auction for $12.4 million.

The metronome, too, became emblematic of another relationship; with renowned photographer Lee Miller. Following their devastating breakup in 1932, the heartbroken artist put an image of her eye on the pendulum.

That same year, in an art journal, he invited others to make their own, with instructions:

“Cut out the eye from a photograph of one who has been loved but is seen no more. Attach the eye to the pendulum of a metronome and regulate the weight to suit the tempo desired. Keep going to the limit of endurance. With a hammer well-aimed, try to destroy the whole at a single blow.”

Despite his international fame, Ray did not receive as much recognition at home. The Inquirer obituary called him “an artistic prophet without sufficient honor in his own country.”

Soon, audiences in Philadelphia will be able to give him a proper homecoming. No destruction required (or allowed).

“Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100″ runs Nov. 8 through Feb. 16 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, 215-763-8100 or philamuseum.org.