By Tom Connolly

Jennifer Ann Redmond’s sympathetic approach to Diana Barrymore’s disastrous life is valuable because it rejects the poor-little-rich-girl tropes. She was more than a debauched debutante or fallen starlet.

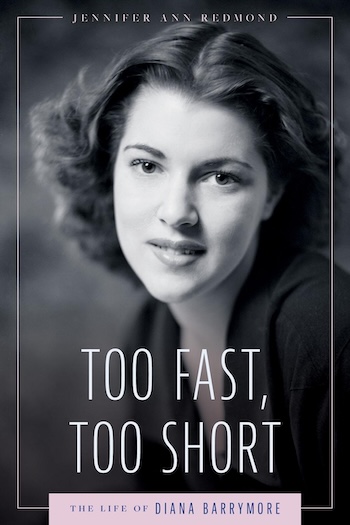

Too Fast, Too Short: The Life of Diana Barrymore by Jennifer Ann Redmond. (Hollywood Legends Series) University Press of Mississippi, 204 pages, $35

This first biography of Diana Barrymore (John’s daughter, Drew’s aunt) is a breviary of the Barrymore burden–too much given, too much expected. Jennifer Ann Redmond delves into the famous theatrical dynasty and the vanished castes of high society. Diana’s father, John, was the Barrymore crown prince; Blanche Oelrichs, a.k.a Michael Strange, her mother, was born into New York’s “400” (as seen in The Gilded Age). Diana’s own tell-nearly-all book, Too Much, Too Soon (1957), set the bar for celebrity bios in more ways than one. In it, Diana’s sad story is depicted as (mostly) a descent into alcoholism. The well- received memoir was filmed a year later, with no popular success. Taken together, these tawdry versions reduced Diana’s image to the face on the barroom floor. To her credit, Redmond sets out to offer a more complex portrait of Diana and she largely succeeds. Moreover, this concise recounting of Diana’s life has the value of complicating the current fixation on “nepo babies.”

This first biography of Diana Barrymore (John’s daughter, Drew’s aunt) is a breviary of the Barrymore burden–too much given, too much expected. Jennifer Ann Redmond delves into the famous theatrical dynasty and the vanished castes of high society. Diana’s father, John, was the Barrymore crown prince; Blanche Oelrichs, a.k.a Michael Strange, her mother, was born into New York’s “400” (as seen in The Gilded Age). Diana’s own tell-nearly-all book, Too Much, Too Soon (1957), set the bar for celebrity bios in more ways than one. In it, Diana’s sad story is depicted as (mostly) a descent into alcoholism. The well- received memoir was filmed a year later, with no popular success. Taken together, these tawdry versions reduced Diana’s image to the face on the barroom floor. To her credit, Redmond sets out to offer a more complex portrait of Diana and she largely succeeds. Moreover, this concise recounting of Diana’s life has the value of complicating the current fixation on “nepo babies.”

On the surface, Diana was the ne plus ultra of nepotism. She could have floated through finishing school, commanded at her coming-out cotillion, and then married a Duke or a Kellogg. Or, she might have spent a few seasons in stock companies and taken her place starring in Broadway shows. She took the latter path initially, but her fabulous name and notable stage debut (in 1940’s Romantic Mr. Dickens) made a turn to the movies inevitable. She went on to make a few mediocre films; her Hollywood career never rose above the B-movie level.

Redmond argues that, because of her pedigree, she never had a real chance. “Nobody Cared” is the final chapter’s title, and it could have been Diana’s epitaph. Her parents were the worst possible combination; a father who left when she was an infant and became a distant dream of a dazzling daddy-figure. Her mother alternated between being controlling and oblivious. A society poet and bizarre blend of bohemian and snob, she always questioned or dismissed Diana’s choices. Blanche wanted to shield Diana from the Barrymores, but wouldn’t quite allow her to take her place in “society.” When Diana was named “Personality Deb of 1938” and rich boys courted her, her mother effectively shooed them away. Diana was allowed to enroll in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, but she did so under an alias that left no one fooled. Ultimately, her parents were generally negligent, and wholly destructive.

Admirers of the legend of John Barrymore will shrink from the details provided here about Diana’s tortured relationship with him. They only met a few times and probably spent only a few weeks together; even so, he still managed to wreak psychic havoc on her. Reuniting with his daughter after many years –when she was in high school — John gave her her first drink. Later that night she had to endure her drunken father’s necking with her best friend, seated next to Diana in a cinema. A couple of years later, Barrymore kicked her out of his dressing room when Diana tried to keep his ex-wife from preying on him. Much worse was to come.

On Diana’s first trip to Hollywood, her mother forbade her to see her father and insisted that she be guarded by a governess. John met her at the train and swept her off to his decaying hilltop mansion. Diana ditched the governess and tried to save her father from himself by staying with him. Barrymore was sunk deep into alcoholism. He’d drive her away again — by demanding she procure him a prostitute. Incredibly, that might be a cover story for attempted incest. In a blackout, he may have tried to seduce Diana.

Unaware of Diana’s dire struggles with her father, the Hollywood publicity machine ground out “Royal Family Reunion” stories. She maintained her celebrity, if not her movie career. But after John Barrymore died, and her box office appeal waned, Diana’s contract wasn’t renewed. She returned to New York; alcohol rapidly began interfering with her stage work, as well as a series of ill-fated marriages with abusive spouses. Diana’s beloved half-brother, Robin Leonard, committed suicide; she took the virginity of her 14-year-old half-brother, John Barrymore Jr., ten years younger than she. When Diana’s mother died of cancer in 1950, the last anchor in her life vanished, and she drifted aimlessly. Pills, booze, and marijuana filled her days.

Unaware of Diana’s dire struggles with her father, the Hollywood publicity machine ground out “Royal Family Reunion” stories. She maintained her celebrity, if not her movie career. But after John Barrymore died, and her box office appeal waned, Diana’s contract wasn’t renewed. She returned to New York; alcohol rapidly began interfering with her stage work, as well as a series of ill-fated marriages with abusive spouses. Diana’s beloved half-brother, Robin Leonard, committed suicide; she took the virginity of her 14-year-old half-brother, John Barrymore Jr., ten years younger than she. When Diana’s mother died of cancer in 1950, the last anchor in her life vanished, and she drifted aimlessly. Pills, booze, and marijuana filled her days.

Diana’s name could still get her work in summer stock. At times she rallied long enough to give a performance that hinted at her talent. Redmond makes it clear that Diana was a good actress. She dazzled Tennessee Williams when he saw her play Blanche in Streetcar and Maggie in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. (Some sources assert that he even wrote a play for Diana.) Williams became a friend, and Diana fantasized about marrying him. That was disrupted when the dramatist would not let her play the Princess in Sweet Bird of Youth — because she was the character. Her performance would have devolved into caricature. (Redmond makes a solid case that the part was based on Diana, not Tallulah Bankhead.) Furthermore, the biographer is persuaded by Christopher Plummer’s claim that Diana got Elia Kazan to let her audition, but she showed up so plastered she could barely stand. This dissolute behavior also wrecked her chance to host the first-ever TV talk show.

By the end of the ’50s, Diana had only her pathetic notoriety to trade on, so she crafted Too Much, Too Soon with Gerold Frank, which generated a considerable readership, partly because it was the prototype for a new genre: celebrities’ making their dirty laundry public. However, the movie version made a year later was a flop, though Errol Flynn’s turn as Barrymore won him late-career laurels.

Within a couple of years, Diana was found dead in her bed; her heart had given out after years of alcoholism and other excesses. At least her maid was thoughtful enough to hide her stash of weed from the cops. Ironically, this post-mortem gesture was one of the few kindnesses Diana ever received. The tabloids tried to sensationalize Diana’s finale. Tennessee Williams claimed an eyewitness told him her bedroom had been trashed, and that she was found with “blood streaming from her mouth.”

The author has immersed herself in Diana’s milieu. A Barrymorephile or student of New York social life will be familiar with the references to Laurette Taylor, Florence Reed, Brenda Frazier, Lucius Beebe, and Walter Winchell. One of the strengths of the book is its ability to recapture the lost world of summer stock and “the road.” Redmond offers colorful looks at Diana’s second and third-rate-theatrical forays; much of her acting career was spent touring through tank towns and summer resorts. Less felicitous is the author’s reliance on her reader’s memory. She will mention a person who matters and expect us to recall who that was thirty pages later. Also, Margaret Wise Brown is vaguely on the scene as a sort of family friend; she is never named as Michael Strange’s lover. Odd, since otherwise the book is LGBTQIA+ aware and accepting. For example, Diana’s doomed half-brother, Robin, is tenderly revealed to have been a lover of Tyrone Power, before the latter became a movie star. Some factual errors follow a familiar pattern in publishing today: the lack of sharp editing. Groton and St. Mark’s are top prep schools in Massachusetts, not Connecticut. More important, for a book largely about the theatre, identifying actors accurately matters. In The Green Bay Tree, James Dale played Dulcimer opposite Laurence Olivier, not Leo G. Carroll, who played the valet.

The book concludes with a nod to Drew Barrymore’s apposite, yet opposite, career trajectory. Diana and her niece, Drew, separated by decades, lived out two variations of “the Barrymore curse”—one tragic, the other curiously redemptive.

Drew began as a tot in films with celebrity threatening to engulf her. Immortalized at six in E.T., she quickly dove into the sybaritic whirlpool: the moppet party girl drunk at seven, coked up by twelve, and rehabbed by thirteen. Drew seemed to be staggering in her aunt’s footsteps, but ending up defying her forebears. Her 1990 memoir Little Girl Lost turned collapse into a prelude to her rebirth Her later career as actor, producer, entrepreneur, and talk-show host is proof thatAmericans don’t always devour their idols, but welcome redemption repackaged as show-biz spectacle.

Diana Barrymore and Lon Chaney Jr. in 1943’s Frontier Badmen.

At this point, the Barrymore saga collides with a broader cultural evolution. As critic Richard Schickel observed of John Barrymore: “One thing is certain: never has our insistence on seizing hold of one aspect of a man’s character and creating from it an immutable screen personality had more tragic results. …[A] talented man forced into one of the most devastating self-exposures in the history of an art based on the display of the self.” For John, that immutable identity was genius in decline; for Diana, it was doomed glamour. Drew has pulled off what Diana couldn’t: she transmuted her public persona into a therapeutic lesson, turning vulnerability into an inspiring performance. In a culture that has become enamored of imperfection—so long as it can be chronicled, televised, or streamed—Drew metamorphosed the art of survival into a brand. Her zesty openness, combined with a heart-on-her-sleeve sincerity, has made her America’s sweetheart.

The evolution of the Barrymore “burden” reflects the shifting terrain of American celebrity. Diana was ravaged by an industry that demanded impossible perfection. Drew thrives in a culture that monetizes confession and that packages resilience as entertainment. Redmond regrets that Diana just missed the “radical cultural shift of the 1960s” because it might have enabled her to find herself. I think not. Diana was a nepo orphan of the storm whipped up by her parents’ egomania and addiction. She knew it herself, writing, “My career would have run along different lines, perhaps if I had been named Brown.” But would anyone have been interested in an actress displaying her self as “Brown,” when that self could have been branded “Barrymore”? Overall, Redmond’s sympathetic approach to Diana’s disastrous life is valuable because it rejects the poor-little-rich-girl tropes. She was more than a debauched debutante or fallen starlet.

Tom Connolly is Professor Emeritus of of Humanities and Social Sciences at Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University. He recently edited a historical study (in English) of the 19th- and 20th-century Jewish community of Döbling for the Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Institut für Kulturwissenschaften. His book Goodbye, Good Ol’ USA. What America Lost in World War II: The Movies, The Home Front and Postwar Culture is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin/PMU Press.