Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Read more

In Surviving the 21st Century by Noam Chomsky and José Mujica, with Saúl Alvídrez (Verso), documentary filmmaker Alvídrez brings together Mujica, former President of Uruguay, and 96-year-old Chomsky, a professor renowned as “the father of modern linguistics”, to debate the major global issues amid the “chaos” of our time. The book is hugely thought-provoking and profoundly depressing. As Chomsky says: “Young people today are faced with the question of whether the species can survive in any decent way, and that is a very real question.” His overriding message, one so necessary in this derivative world, is “think for yourself!”

The annual literary festival at Hay-on-Wye is a great cultural event of the year, and one of the key figures behind its founding and subsequent success is given his due in James Hanning’s charming biography The Bookseller of Hay: The Life and Times of Richard Booth (Corsair). The book neatly captures a bygone age of eccentricity.

I also enjoyed Sebastian Faulks’ Fires Which Burned Brightly: Ten Essays in Place of a Memoir (Hutchinson Heinemann), which includes a witty chapter on his spell in journalism – including a job at the Independent, where he commissioned and edited reviews of new books.

A particularly moving memoir is Elizabeth Gilbert’s All the Way to the River: Love, Loss and Liberation (Bloomsbury), in which the author of Eat, Pray, Love recounts her deep devotion to musician and filmmaker Rayya Elias, her partner who died from cancer in 2018. The book, which traverses themes of addiction, takes several shocking turns, including an admission from Gilbert that she had plotted to murder Elias.

There are also a host of fine new novels out this month. Two I would particularly recommend, both for their humour and wisdom, are Patricia Lockwood’s Will There Ever Be Another You (Bloomsbury Circus) and Tom Cox’s Everything Will Swallow You (Swift).

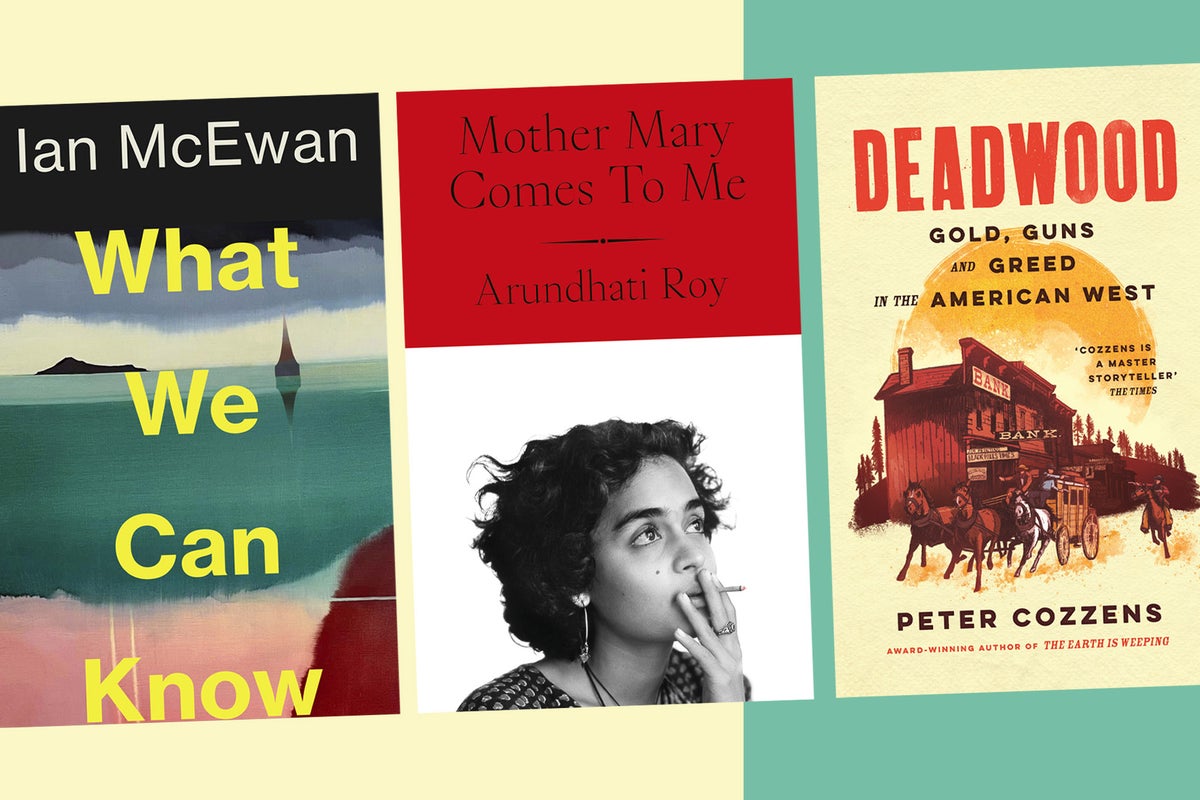

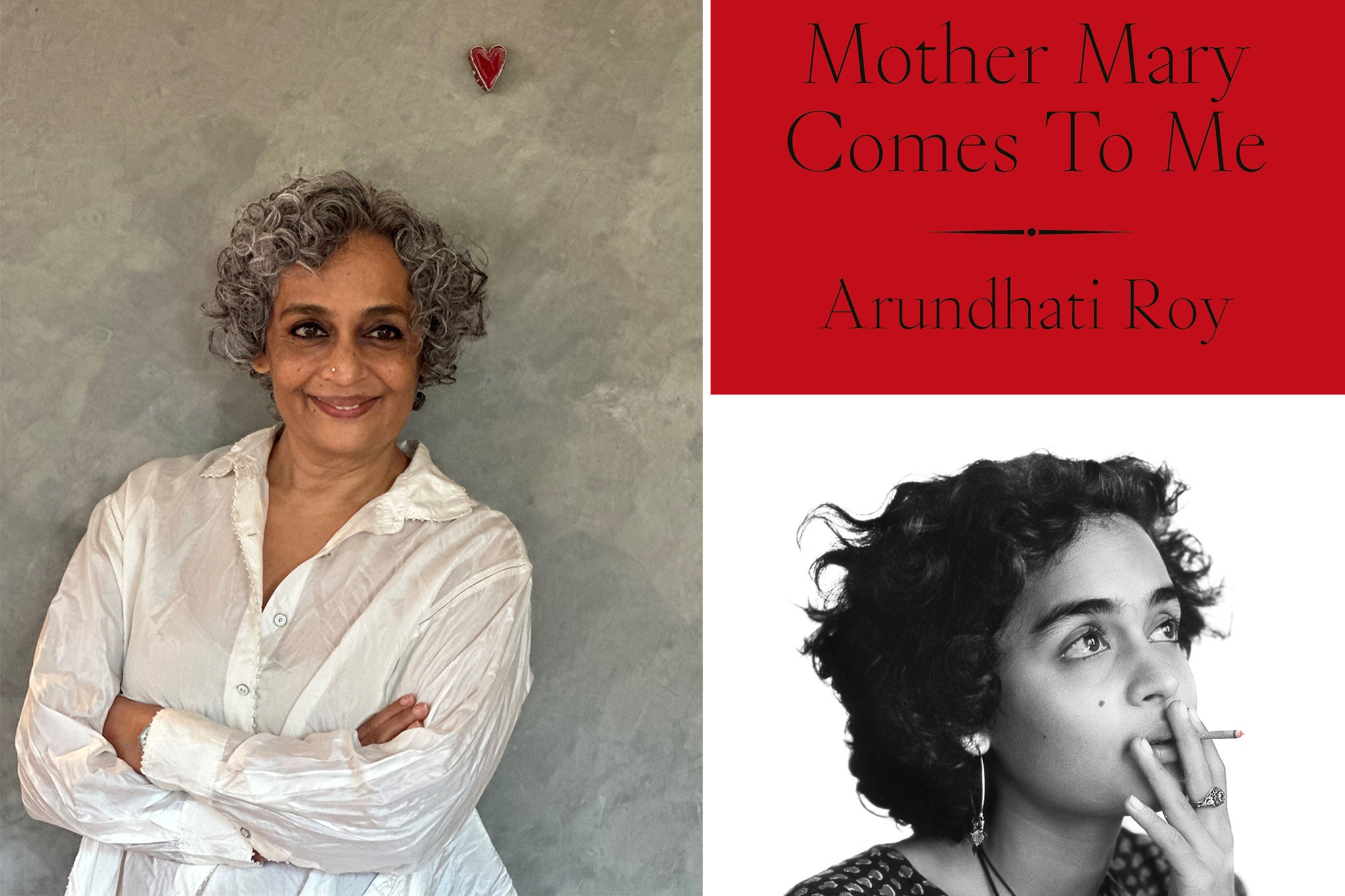

Memoir of the Month: Mother Mary Comes To Me by Arundhati Roy

★★★★★

open image in gallery

(Mayank Austen Soofi/Penguin Random House)

“My mother conducted herself with the edginess of a gangster,” writes novelist Arundhati Roy in her memoir Mother Mary Comes To Me. She is putting it mildly. Mrs Roy the matriarch had anger issues that would have made Al Capone blush. There was no Mr Roy around as Roy grew up. He was an alcoholic, absent drunken father, whom the author of the fabulous The God of Small Things sometimes referred to simply as The Sperm.

Arundhati, born in northeast India in 1961, and her elder brother Lalith Kumar Christopher Roy (she calls him LKC), both faced the “abusive bullying wrath” of their remarkable mother, who founded and managed an extraordinarily progressive educational institution in Kerala. She upbraided her son with the words, “You’re ugly and stupid. If I were you, I’d kill myself”; she told her daughter “You’re a milestone around my neck. I should have dumped you in an orphanage the day you were born,” and subsequently detailed the ways she tried to abort her in early pregnancy. It is no surprise that Roy grew up with “a constant sense of dread”, which she lyrically calls “the cold moth on my heart”.

At times, the memoir reads like a self-analysis session in which the novelist is trying to work out her complicated feelings about her “brittle relationship” with her mother, and why the old woman’s death at 89 in 2022 left her “wrecked and heart-smashed”.

The book is also an indictment of men. Bad-tempered, violent and predatory males litter the memoir, including the grandfather who whipped his children and split his wife’s scalp open with a brass vase. Another grandfather snuffled and groped down Roy’s underwear when she was a child. She recalls that while everyone else saw a “loving, bumbling grandpa”, she knew him as a “human-sized pig with glasses, a snorting wild boar sitting across the table from me at mealtimes”. Roy details a deeply sexist society, from the rape-obsessed films to the daily perils of being molested on public transport. “Delhi’s male commuters thought of women as snacks they could help themselves to whenever they felt like it,” she writes.

The scale of this beautifully written book is impressive. Roy describes her own poverty and drug-taking in her student days, a kidnapping threat that followed in the wake of the notoriety from her appearance in a movie, and the horror of an abortion without anaesthesia. She is revealing about her writing career and the path that led to her masterpiece, The God of Small Things – and witty about the literary prize circus she faced upon winning the Booker in 1997.

Her tangential recollections are sharp, too, including her view of the phoney flower-power hippies who invaded India in her adolescence (“I saw in them small-heartedness, calculation and overt racism”). She also explains why she finds most resonance in the people “defeated by life”.

The final section of Mother Mary Comes to Me covers her time as a “writer-activist” – a term she mockingly says sounds a bit like a sofa-bed – and you can’t help but admire her courage in the face of insults, a jail sentence and the death threats that have followed her exposé essay and reportage of Islamophobia, corruption, the mass slaughters of Muslims and the depravity and cruelty that is modern Kashmir.

It is a total pleasure to spend time with Arundhati Roy’s mind and memory in this funny, wise, candid and perceptive memoir.

‘Mother Mary Comes To Me’ by Arundhati Roy is published by Hamish Hamilton on 4 September, £20

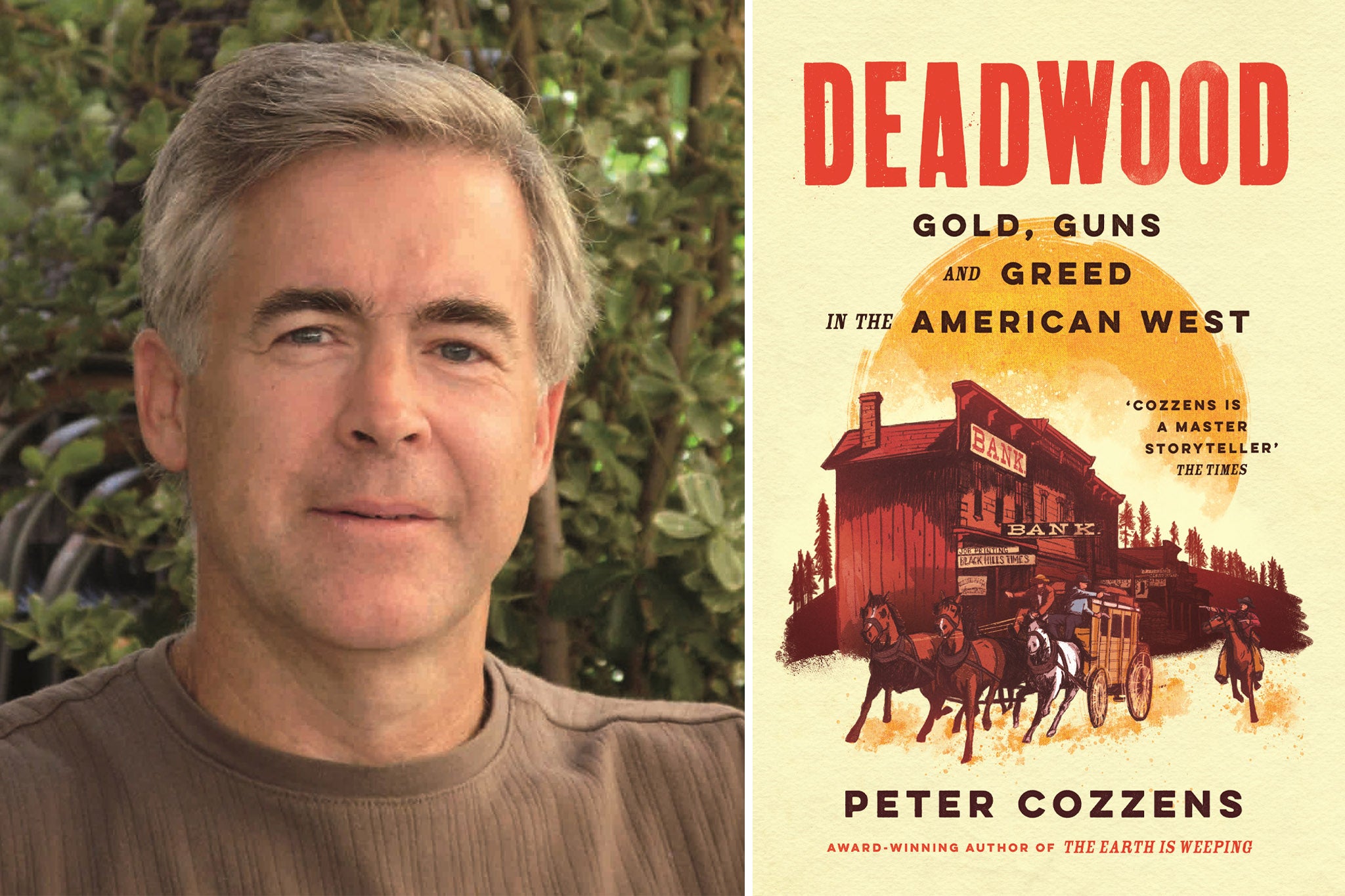

Non-fiction Book of the Month: Deadwood: Gold, Guns and Greed in the American West by Peter Cozzens

★★★★☆

open image in gallery

(Antonia Feldman/Atlantic Books)

Deadwood, David Milch’s “Old West” series for HBO, was notorious for its filthy mud and filthy script (there were 2,980 uses of the F-word during its three seasons) and anyone who loved that show will enjoy Peter Cozzens’ detailed, enlightening history of the famous town in the northern Black Hills region of South Dakota. Cozzens, a well-regarded historian, captures the feel of the place (he refers to the “fly-infested slop that passed for Main Street”) and reminds us that the real Deadwood and the Deadwood of myth were built on land stolen from the Indians.

Cozzens certainly has some great central figures to work with, including Wild Bill Hickok, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and Calamity Jane. Calamity was born Martha Canary. Her nickname possibly derived from the fact that it was clear she was a human calamity. The book details her life sympathetically, up to her death at 47 from inflammation of the bowels, a direct result of her alcoholism.

Deadwood had two dozen brothels, and Cozzens details the atrocious treatment of sex workers in the 1860s, including by owner Al Swearingen (played so brilliantly by Ian McShane in the television series) and his violent henchman Dan Dority. Perhaps it is no wonder that Deadwood was described as “wicked” by The New York Sun newspaper at the time. Cozzens writes of a local teacher in 1861, a woman called Minnie, who used to stand on her head to amuse her pupils. He adds that most women in Deadwood wore “crotchless undergarments” so the pupils might have been a little more than amused.

Cozzens explores the racism of the era, too. Deadwood had around 50 Black residents in this era, although the Chinese residents seem to suffer more severe treatment from the frontier population. The historian cites the “random brutality” towards Chinese immigrants and the constant slurs directed at Chinese women. He says they were dubbed “moon-eyed pinch foots”, a reference to the practice of feet-binding in China.

Deadwood is a serious, well-researched history of a fascinating town – one that grew rich on gold and timber during the economic boom after the Civil War. Even those familiar with the television series will learn more about the hidden history of Deadwood. It is strange to think that in such a violent and dehumanised place, baseball was a popular pastime.

‘Deadwood: Gold, Guns and Greed in the American West’ by Peter Cozzens is published by Atlantic Books on 4 September, £25

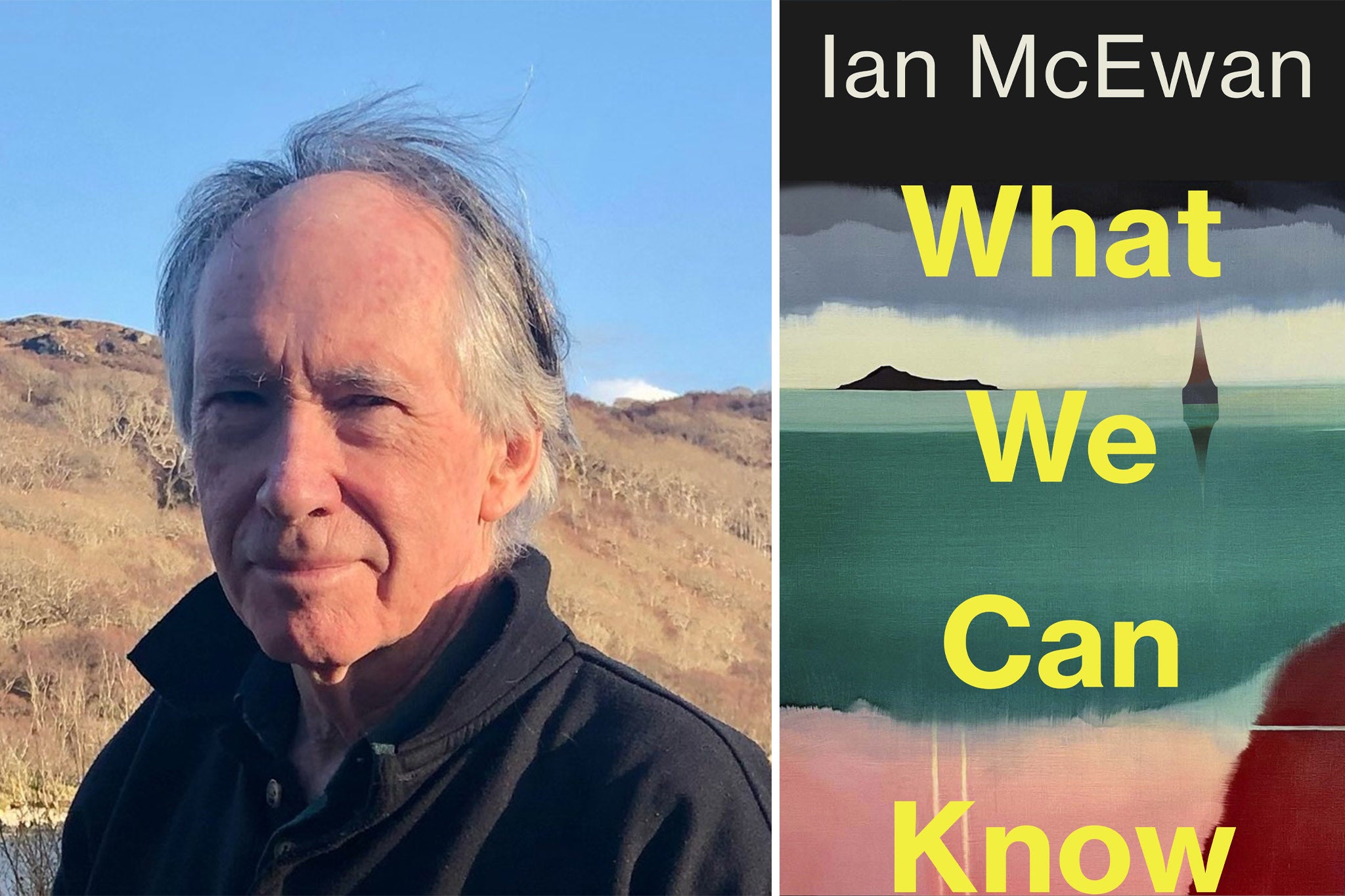

Novel of the Month: What We Can Know by Ian McEwan

★★★★☆

open image in gallery

(Penguin)

Ian McEwan’s 19th novel, What We Can Know, is about time and our relationship to the past and the future. In 2119, Tom Metcalfe, a historian at the University of the South Downs – part of Britain’s remaining island archipelagos – is trying to piece together the truth about a mysterious poem written in 2014. The poem, A Corona for Vivien, was written by celebrated poet Francis Blundy to his wife Vivien, a gift on her 54th birthday. The supposed literary gem has been lost for more than a century.

McEwan’s dazzling novel switches between the future and our own 21st-century era, one in which we are setting in motion catastrophe by degrading nature. McEwan contrasts the climate denial views of Blundy with the caustic appraisal of our times by his 22nd-century students. They believe that boneheaded greed brought deserved mega-deaths and that people of our era were simply “morons” fighting stupid wars. “The warming they ignored, the animals they killed, how skin colour meant so much” is one verdict – and they certainly don’t want Metcalfe’s nostalgia. They also don’t want golf – a game that is deemed to take up too much space once the sea has invaded the land.

Although McEwan is imagining a possible (horrendous) future, in which warlords slaughter for North American territory and a dominant Nigerian empire controls the Internet following the Third Sino-American Wars (Britain has wars with France), he is also examining what will be lost from our present when we throw it away with our scorched earth mentality.

The writing has McEwan’s usual elegant quality and there is neat humour at play, too. Although a quip about Jimmy Savile feels shoehorned in, there is plenty of wit in the many passages that reveal human vanity and foibles. At the heart of the “plot” is a renowned poetry-reading at a famous 21st-century dinner party, hailed as one of the most significant cultural moments of our time. McEwan cleverly uses the recollections of participants to instead expose the truth about a drunken and rather tiresome evening. Readers can decide for themselves, too, whether it is comforting or dispiriting that the same emotional entanglements and fears of betrayal preoccupying couples in the 21st century will remain a hundred years hence – plain to see in the relationship between Metcalfe and his partner Rose.

The novel is broken into two sections. Part Two reveals the story from the perspective of Vivien, who is the strongest character in the novel. This includes an account of dealing with the Alzheimer’s bedevilling her first husband, Percy. Anyone who has suffered the pain of watching a loved one with dementia will be bowled over by the grace and mournful accuracy of McEwan’s descriptions, particularly the way he captures the strange moment when lucidity returns to a dementia victim for the final time. The author compares it to being like a drowning person “breaking the surface to gulp air for the last time”.

In this section – no spoiler – readers also discover the secret Faustian bargain between Vivien and Francis, one that explains everything about the poem’s secret fate and the reality of the much-vaunted love supposedly immortalised in the ode.

I enjoyed What We Can Know despite its morbidity. The novel has telling things to say about the way scruples can be “worn smooth”. It certainly has an eloquent fury about the way our misguided present is allowing nature to shrivel by “slow roasting”. What We Can Know is also a book about the complications of nostalgia. “It comes without warning, like a slap,” writes 77-year-old McEwan.

‘What We Can Know’ by Ian McEwan is published by Jonathan Cape on 18 September, £22