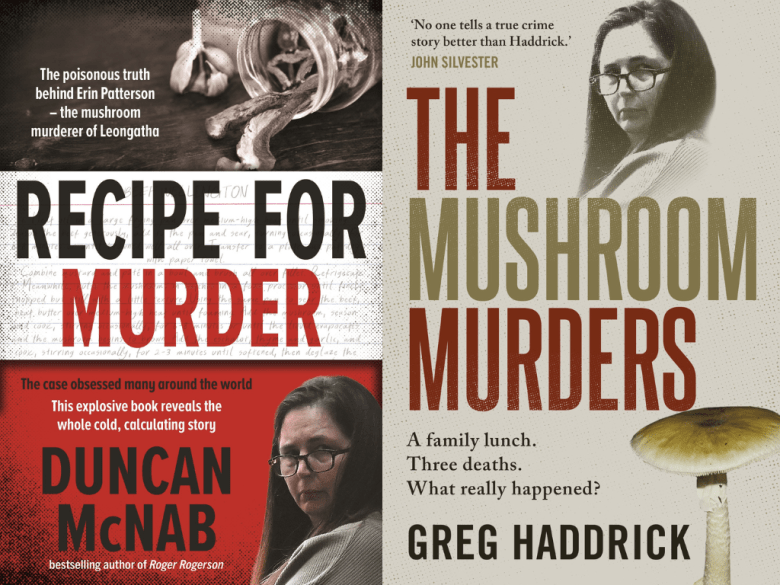

ReadingRoom doth not review, mention or acknowledge books published by anyone other than New Zealanders. But it’s the exception which proves the nationalistic rule, and two new books on the same extremely diverting subject, the death cap mushroom poisonings in Victoria which led to the conviction of Erin Patterson on three charges of murder, sneak in under the radar on account of the small but revealing forensic link with New Zealand, also the strange neighbourly familiarity we always feel with anything going over the ditch at that weird continent.

Recipe for Murder by Duncan McNab is a straightforward telling of the facts of the matter. It pokes around the town where Patterson served her lethal meal of beef Wellington with death cap mushrooms on July 29, 2023, and it reports from this year’s 11-week trial at the Supreme Court of Victoria. The author can’t write his way out of a paper bag. “That fateful day … the horrific consequences … that dreadful day … quiet lives in the close-knit rural towns … this close-knit town … the dreadful fate”, etc. But the story itself is powerful. It’s rare that a trial from anywhere else in the world is able to exercise the New Zealand mind and Patterson’s case was followed here avidly. I found this fascination at once hard and easy to understand. It didn’t have a lot going for it inasmuch there was no sex, no wealth, and, curiously, no apparent motive. What it did have was food. The dark force of the Patterson story is imagining her folding in the death cap mushrooms into her pastries, the little practical allegedly premeditated steps in the kitchen … Recipe for Murder is a tactless but forceful title.

The Mushroom Murders by Greg Haddrick tells the story in a highly original manner. The author invents a juror, a middle-aged woman who runs a picture-framing business, and steps inside her mind. “This book imagines the journey one of those jurors might have taken to reach their verdict. The story here is told to us by a fictional juror. I wanted readers to feel they were on that journey with the jury.” It is a 100 percent shit idea, a shit idea for the ages, full of terrible asides (“My head was spinning … I could’ve been wrong. A divorced, middle-aged woman with a thyroid problem, renting a one-bedroom apartment in a country town, has conceivably been wrong many times before … Lord love a duck”) and full of shit. It’s so excruciating that you long for McNabb’s meathead tabloidese. But the same central appeal of the Patterson case works its magic on Haddrick’s book, too.

There are a million ways to die and the Australian continent is packed with incredible threats. Alligator. Shark. Dingo. And, in the shade of oak trees, death cap mushrooms, which Patterson accepts she foraged and placed into the lunch on that day so fateful and dreadful. Her defence was that she did not do it knowingly. The victims were her ex-husband’s parents Gail and Don, and aunt Heather. The aunt’s husband Ian went into a coma. He survived. Patterson claimed she served herself a portion, too, but purged it immediately after lunch. Her version was that she scoffed two thirds of an entire orange cake for dessert; ashamed of herself, she kneeled over the toilet and vomited.

She was found guilty. She has appealed the verdict. Was it a travesty of justice? Australia has been down that road before with Lindy Chamberlain but Recipe for Murder and The Mushroom Murders both slam the jail door on Patterson with the usual righteous satisfaction of crime journalism.

McNabb writes in full meathead journo wrath, “The cold, hard truth is Erin Patterson did indeed cook up a recipe for murder … She has demonstrated no remorse for her actions.” It’s generally quite difficult to demonstrate remorse when you know yourself to be innocent.

Haddrick goes through his annoying juror. “I had often wondered how on earth Erin ever thought she could get away with lacing food with poison. The answer is now clear to see: because she already had. Three or four times before.” Haddrick means the times that Patterson’s ex-husband Scott became violently ill after she cooked for him. “On all previous occasions, she had outsmarted the medical profession. And she had always thought doctors were dolts anyway. Why would she think her beef Wellington lunch would be any different?”

In Recipe for Murder, Duncan McNabb walks the mean streets of his small-minded tabloid neighbourhood when he tries to imagine what Scott was thinking after falling sick from eating meals his ex-wife prepared. “He hadn’t begun to entertain the dark thoughts that the woman he still loved may be trying to kill him. But that reality was soon to dawn.” No one talks like this in real life. The only people who write like this are content providers.

Greg Haddrick’s narrarting juror is less inclined to cliché. The writing of The Mushroom Murders is subtle, thoughtful, patient. The book concludes, “The only reasonable conclusion we could draw from the whole of the evidence was that Erin had picked death cap mushrooms in April and May of 2023 and she had dehydrated them and stored them. She had planned a lunch for no other purpose than to use those death cap mushrooms, and she had then created a menu that allowed her to separate poisoned portions from safe portions. Everything else that followed was an attempt to hide, blur or contradict those actions. And the only reasonable conclusion was that all those actions had been intentional.”

Nicely and convincingly put. Both books wonder about motive, and the child-care dispute that seemingly was the root of it. Both books expose Patterson’s various lies and concealments, such as the curious incident of the Samsung she bought on holiday in New Zealand. Patterson and her two kids travelled here in the summer of 2023. The screen on her phone broke. She bought a replacement Samsung. Haddrick: “For the rest of 2023, right up until the infamous lunch on 29 July, and even a few days beyond that, Erin’s personal phone, the one she used every day, was that new Samsung A23 … And it became important because that phone has never been found.”

Both books are fast reads, throwaway junk that nevertheless succeed in taking you there, to the trial and to the essential parts of the story of Patterson, a true-crime fan who has made her own historic contribution to true crime. Both books provide a fix for death cap mushroom case junkies. But a third book is due in November: the keenly anticipated The Mushroom Tapes by Helen Garner. Helen Garner is a genius. Her book This House of Grief is a classic work of crime literature. Worryingly, though, her book on Patterson is co-authored with two other writers. What the hell? The publishers describe it as a “record of their private conversations about their impressions from inside the courtroom. They explore the gap between the certainties of the law and the messiness of reality, their own ambivalence about the true-crime genre, and all that remains unknowable about Erin Patterson.” Three authors sounds like a crowd. Like Haddrick’s fictional juror, it feels over-complicated, a conceit.

Maybe the dreadful McNabb has made the Patterson book you want. He may even have a heart. He writes of an intensive care specialist who gave evidence, “I’ve been attending court cases for nearly five decades, and the evidence we’d heard that morning – the mechanics of slow and horrible death – was the saddest I can recall.” The specialist described the acute liver failure suffered by the poisoned victims. One of them was given a liver transplant. The other two were too ill to attempt it. All three died.

Recipe for Murder by Duncan McNabb (Hachette, $39.99) and The Mushroom Murders by Greg Haddrick (Allen & Unwin, $37.99) are available in bookstores nationwide.