A major fossil discovery about our ancient ancestor has occurred in Kenya.

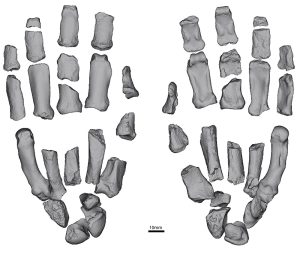

Researchers have found hand and foot bones belonging to Paranthropus boisei — an extinct human relative who lived over 1.5 million years ago.

There was a long debate around this species about whether these ancestors could make and use stone tools.

The team from Stony Brook University in the US states that this discovery of the first clearly identified hand and foot bones settles the debate about P. boisei‘s capabilities.

It turns out, the ancient cousins “had human-like dexterity with gorilla-like gripping strength.”

“This is the first time we can confidently link Paranthropus boisei to specific hand and foot bones,” said Carrie S. Mongle, a paleoanthropologist and assistant professor of anthropology at the university.

“The hand shows it could form precision grips similar to ours, while also retaining powerful grasping capabilities more like those of gorillas, and the foot is unquestionably adapted to walking upright on two legs,” added Mongle, who led the study.

Carrie Mongle (left) and Meave Leakey discussing the new Paranthropus boisei hand fossils at the Turkana Basin Institute research station in Ileret, Kenya. Photo Louise Leakey.

Carrie Mongle (left) and Meave Leakey discussing the new Paranthropus boisei hand fossils at the Turkana Basin Institute research station in Ileret, Kenya. Photo Louise Leakey.

Fragmentary hand remains

Paranthropus boisei, an ape-like evolutionary relative of Homo sapiens, diverged from a shared australopith ancestor over 3 million years ago.

Living in eastern Africa between 2.6 and 1.3 million years ago, P. boisei coexisted with at least three other hominin species: Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, and Homo erectus.

The species’ molars were up to four times larger than the molars of people alive today.

Fossils previously were mostly just skulls and teeth. Without a complete skeleton, researchers couldn’t know what the body looked like or how the hominin behaved in its habitat.

The partial skeleton was excavated from Koobi Fora in Kenya.

Dating back roughly 1.5 million years, the recovered fossils consist of cranial pieces, teeth, and a set of hand and foot bones.

P. boisei possessed “human-like hand proportions,” which enabled it to manipulate stone tools like early Homo.

However, its hands were not fully modern. The species lacked the specialized wrist anatomy seen in later humans and Neanderthals

This finding is significant because Homo and Paranthropus fossils are often found together with stone tools, which have been attributed only to Homo.

Diet of tough plant foods

The recent fossil find intensifies the discussion about the differing ecological roles of early hominin species.

The evidence suggests that while species belonging to the genus Homo increasingly relied on using tools, Paranthropus followed a different evolutionary path.

Its distinctive adaptations — seen in its face, massive teeth, powerful jaws, and now its hands — point toward a highly specialized diet of tough plant foods, rather than a heavy dependence on tool technology. This essentially highlights two distinct survival strategies evolving side-by-side.

“This discovery helps us understand a lot more about Paranthropus boisei, especially how its hand shared similarities with members of our own genus Homo while evolving its own capabilities,” said Caley Orr, a co-author from the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

The powerful hand structure of P. boisei evolved to resemble that of a gorilla, which would have been useful for gathering and processing tough plant foods.

Furthermore, these grasping abilities would have also helped climb.

The research was supported by funding from the National Geographic Society and the Stony Brook Research Foundation.

The findings were published in the journal Nature.