LONDON—This past week, U.K. long-term borrowing costs hit their highest level in decades, causing Treasury chief Rachel Reeves to shoot down suggestions that the heavily indebted country is heading for a fiscal crisis.

PREMIUM The U.K. is expected to increase taxes again, partly to offset rising borrowing costs.

PREMIUM The U.K. is expected to increase taxes again, partly to offset rising borrowing costs.

Most economists agree with her—for now. But in a world where industrialized nations have taken on record amounts of debt and are paying ever more to finance the borrowing, the U.K. could become the financial markets’ equivalent of the proverbial canary in the coal mine—a leading indicator of trouble for other debtors like the U.S. and France, economists say.

“The U.K. isn’t alone in all of this,” said Ruth Gregory, deputy chief U.K. economist at Capital Economics. “There is a common theme across many G-7 countries that the conditions do seem to be in place for a potential fiscal crisis, although that doesn’t mean a crisis is imminent or inevitable.”

Last year, the British Labour government announced the biggest tax hike in a generation, billed as a one-off effort to plug a widening shortfall in public finances and reassure investors that the U.K. was a country serious about balancing its books. But now, Reeves is expected to return in November to ask British taxpayers for billions more in taxes.

The reason: The U.K.’s borrowing costs keep rising, its economy isn’t growing as fast as hoped, and the government, despite having a healthy majority in Parliament, has struggled to cut ballooning welfare spending. Economists worry the pattern could keep repeating.

Over the past two decades, governments went on a debt binge, fueled by low interest rates. Now that rates have risen, investors worry that Western governments aren’t willing to make politically difficult decisions to curb public spending, leaving politicians caught on a hamster wheel of ever higher taxes. France’s government is expected to fall in the coming week amid political opposition to proposed spending cuts and the elimination of two public holidays—a move to raise tax revenues from two more working days.

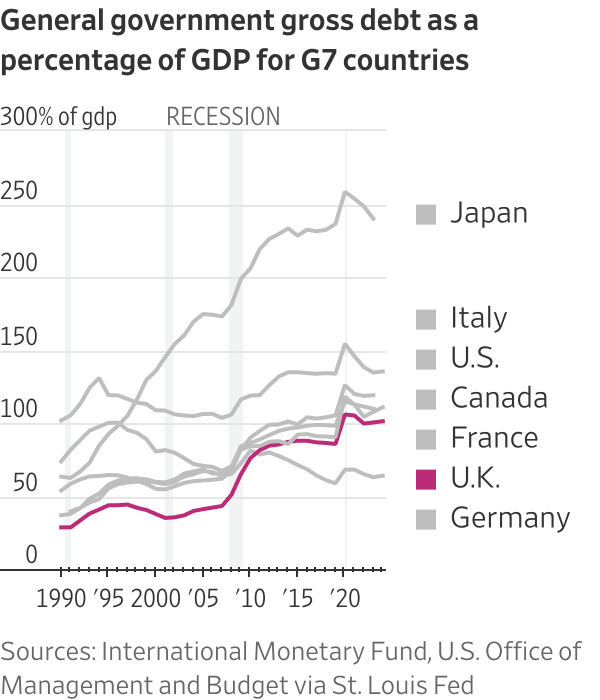

The amount of debt as a percentage of annual economic output in advanced economies has doubled since 2007 to around 80%, according to the International Monetary Fund. The IMF says public debt could rise close to 100% of the global economy by the end of the decade, in part because of rising interest costs.

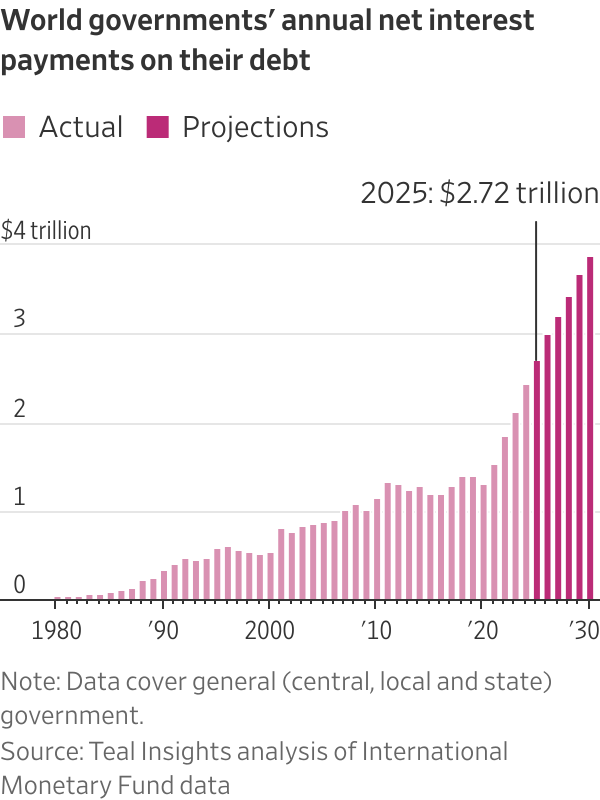

In the last year, net interest payments on government debt across the globe rose 11.2% to $2.72 trillion, partly driven by stubbornly high inflation that keeps interest rates high.

The U.K. isn’t the most indebted Western country, nor is it the slowest growing. Unlike the U.S., however, it doesn’t have a major reserve currency. And unlike its European neighbors, it isn’t part of a currency club with a big central bank that helped engineer bailouts of debt-laden countries. It also has a recent history of market turmoil, when the pound crashed in 2022 after then Prime Minister Liz Truss signed off on unfunded tax cuts combined with big borrowing. (Truss was ejected from Downing Street within weeks.)

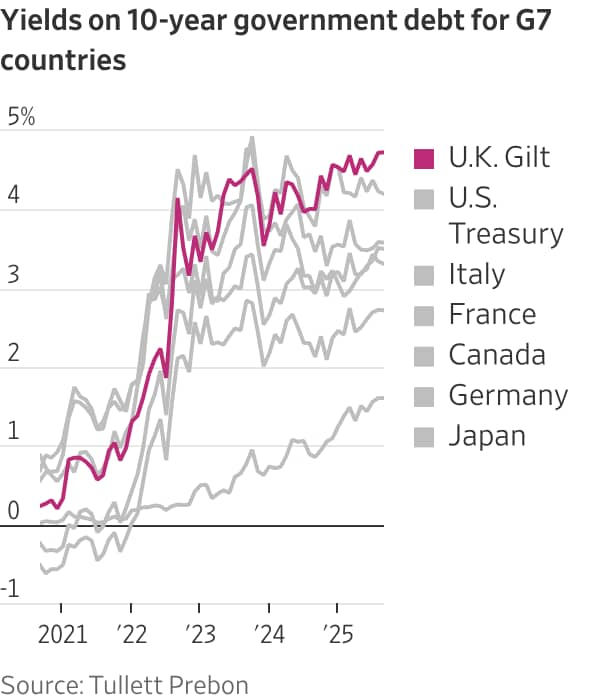

Investors now demand a slight premium to lend to the U.K., whose borrowing costs have risen sharply in recent years, partly as a result of persistently high inflation. Yields on 30-year government bonds, or gilts, this past week hit levels last since in the late 1990s, rising higher than those of France, which has a bigger debt load. The yield on U.K. 10-year debt is now the highest in the Group of Seven nations, eclipsing the U.S.

“There are countries that have got higher debt levels or higher deficits, but when you look at what you’re having to spend in terms of borrowing costs that’s where it becomes problematic,” said Mark Dowding, chief investment officer for fixed income at RBC BlueBay Asset Management.

Next year, the U.K.’s interest payments are expected to hit £111.2 billion, or roughly $150 billion, twice what the country spends on defense. U.K. government debt, currently below 100% of gross domestic product, is projected to hit 270% of GDP by the early 2070s, pushed up by an aging population and spending on healthcare and pensions, according to the country’s fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility.

This combination has turned the U.K. into a potential tinderbox, where a market crisis, either at home or abroad, could trigger yields to jump up further, said Gregory of Capital Economics.

Some argue that precisely because the Bank of England is independent and unlikely to bail out the government, the country will be a “first mover” in facing up to the reality of its borrowing glut since the pandemic. “It’s going to be a mess, it’s going to be painful, but the U.K. will at least confront the problem,” said Robin Brooks, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. Others might not until there is a crisis.

As things stand, an immediate repeat of the Truss market meltdown is unlikely, said Francis Diamond, head of European Rates Strategy at JPMorgan. The pound has risen against the dollar over the past year, a far cry from the steep falls seen under Truss or when the country was bailed out by the IMF in the 1970s.

But the overall trend isn’t positive. The Labour government, elected last year, vowed to be fiscally responsible. But its first efforts this year to trim the growth in welfare spending were knocked back by its own lawmakers in Parliament. In July, Reeves appeared tearful in Parliament after plans to make a modest welfare cut were abandoned as Labour’s own lawmakers threatened a rebellion. A plan to cut a fuel subsidy to the elderly also had to be shelved.

That, say economists, leaves Reeves with a very difficult balancing act when she presents spending plans this fall: finding a way to raise taxes but not crush growth.

Write to Max Colchester at Max.Colchester@wsj.com and Ed Ballard at ed.ballard@wsj.com

Is the U.K. a Canary in the Coal Mine for a Heavily Indebted World?

Is the U.K. a Canary in the Coal Mine for a Heavily Indebted World?  Is the U.K. a Canary in the Coal Mine for a Heavily Indebted World?

Is the U.K. a Canary in the Coal Mine for a Heavily Indebted World?  Is the U.K. a Canary in the Coal Mine for a Heavily Indebted World?

Is the U.K. a Canary in the Coal Mine for a Heavily Indebted World?