Gynecological malignancies in women are a major public health concern since they are common and often fatal diseases. Cancer cervix (CC) is the second most common cancer in women globally, following breast cancer, and ranks first among gynecologic cancers. Globally, about 266,000 women die annually from CC, with 87% of these occurring in less developed areas [22].

Since cervical dysplasia is a preventable disease with early detection, a key approach to prevention is to increase public awareness and ensure that healthcare personnel possess accurate knowledge regarding prevention and screening techniques [23]. The National Cervical Cancer Coalition (NCCC), a nonprofit organization dedicated to the prevention of cervical cancer and HPV disease in collaboration with WHO, has asserted that it is essential for all healthcare workers to offer counseling and health education on CC prevention to females, it also emphasizes on enhancing the knowledge of healthcare practitioners to educate people about CC prevention, screening, and early detection, and contribute to effective struggle against CC. Upon reviewing the literature, it is evident that healthcare providers across the world possess a limited degree of knowledge regarding CC early diagnosis, prevention, and screening [4, 5, 10, 21].

Of 1300 study participants, only 14.8% received further education or training about cancer cervix screening after graduation. The matter that implicates the observed limited information and infrequent updates contributes to the low acceptance of screening.

Our figures are consistent with a study conducted by Altunkurek S., (2022) in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, it studied the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare providers, who found that 22.1% of the respondents declared that they got training on CC as a part of their vocational training. Also, noted that 16.8% of the participants received in-service training after graduation, and the remaining said that they did not receive any training [23]. Similarly, the current study findings are consistent with the study conducted by Mwalwanda A., et al. (2024) in Indonesia, which reported that 84.3% of participants didn’t have CC screening education as a component of the facility program [24].

Findings were replicated by Habas et al. 2025 who demonstrated, that most of participated women didn’t receive any education on cervical cancer throughout their life [25].

Concerning risk factors of cervical dysplasia, the present study elucidated that the majority in all groups agreed that having several sexual partners, early sexual intercourse, infection with HPV and HIV, cigarette smoking, and positive family history of CC were potential risk mediators. This finding aligned with Majid E et al., (2022) study in Karachi, Pakistan, which revealed that the frequently observed risk factors were multiple sexual partners (73.2%), initiating sexual intercourse at a young age (46%), smoking (37.8%), foul-smelling discharges (63.7%), and post-coital bleeding (66.6%) [26]. Similarly, a study conducted by Mwalwanda A et al., (2024) revealed that 18.6% and 15.7% of study participants respectively identified multiple partners, and early sexual debut as risk factors [24].

The study identified a notable good knowledge of participants regarding the methods of cervical cell disorders screening, as more than half of study participants in all professions were aware of Pap smear as a screening method, believed that visual inspection of the cervix, human papillomavirus DNA testing, and liquid-based cytology are methods of screening. On the same line, Dulla D, et al., (2017) in Ethiopia declared that (77.1%) of responders were aware of methods used to detect premalignant cervical lesions, and (37.6%) of them identified visual inspection with acetic acid as a screening approach [27].

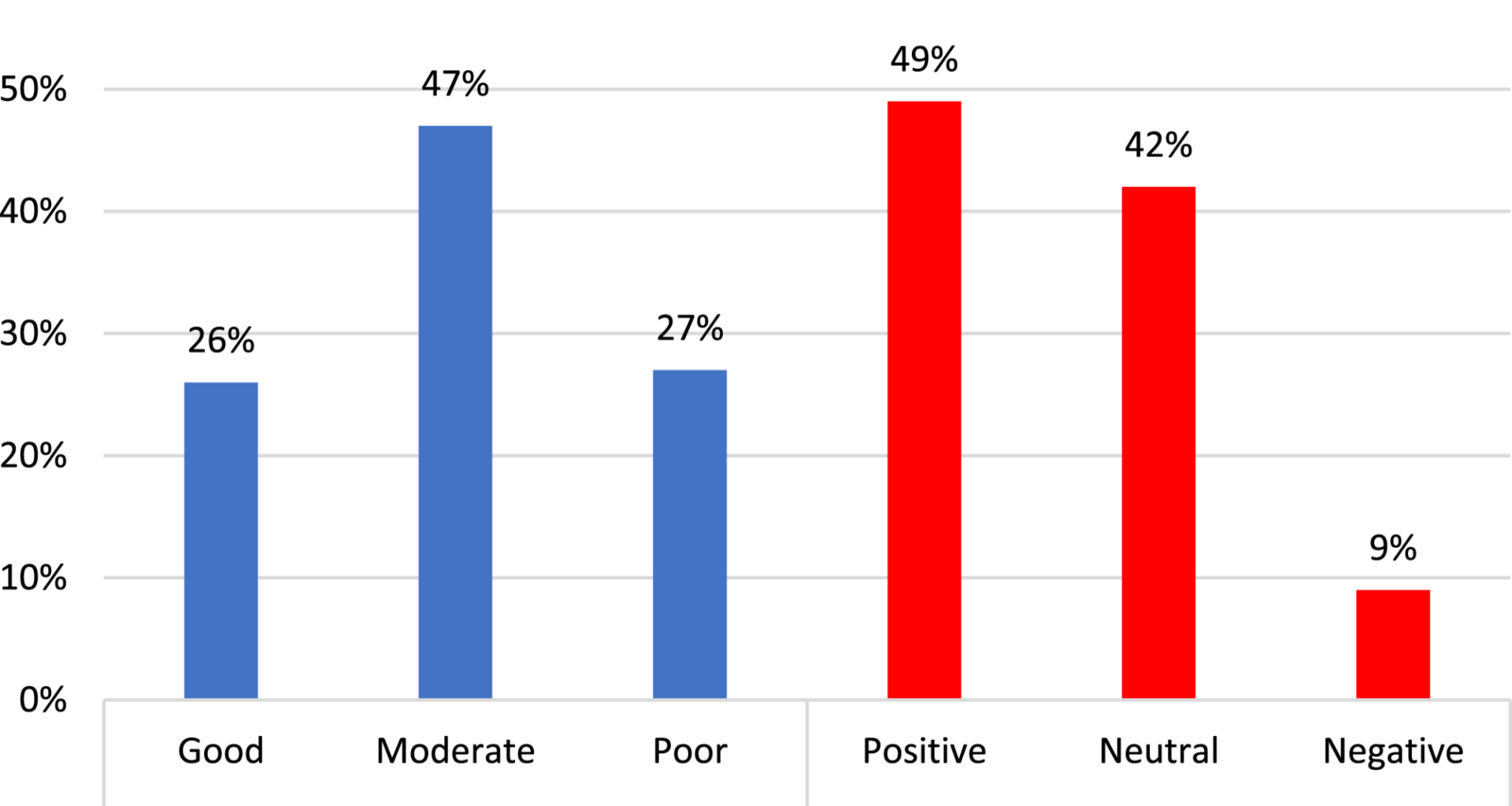

Concerning the total level of knowledge within the four groups, the major proportion in groups I, III, and IV(55.3%, 56.5%, and 40% respectively) possessed a fair level of knowledge. 46.7% of Group II had a good knowledge. The observed discrepancy could be attributed to variations in the scientific backgrounds across the four professional groups.

The consistent finding was reported by Abebaw, E. (2022) in Northwest Ethiopia and highlighted that 44.3% of the respondents knew the risk factors related to cervical cancer, while 43.8% of females demonstrated sufficient knowledge regarding cervical cancer screening [28].

Moreover, Chawla B., (2021) who conducted a systematic review of a total of 22 studies and included 6811 health professionals in India, polled that the general knowledge of CC among health professionals was 75.1% and the awareness level of risk factors was considered sufficient [13]. Likely, Obol JH et al., (2021) who conducted a study on healthcare professionals in Uganda observed that 60% of the participants showed sufficient knowledge concerning cervical cancer [29].

Notably, a similar study was held between Egyptian working women, revealed that 76% of respondents had poor knowledge level regarding cancer cervix, the majority 81.2% expressed negative attitudes towards cervical disorders and early detection screening and only 5.3% performed Pap smear test [14].

In contrary with our figures, a similar study conducted by Heena H, (2019) in Saudi Arabia displayed that only 4% of responders had good knowledge [30]. Another study conducted by Ampofo et al. (2020) revealed that nearly 82% of women in Kenyan, Southern Ghana, have poor knowledge regarding cancer cervix [31]. The discrepancies between studies may be due to differences in personal beliefs, information, policy, time, training opportunities for the care providers, and variability in healthcare policies within the study areas.

Concerning the participants’ attitudes about cervical dysplasia, 60% of the women in group II stated that it is highly common and a primary cause of mortality among all types of cancer. In group IV, 64% of respondents declared that any young woman has a chance to obtain CC. In group I, 68.1% of females accepted the belief that cervical cancer is not transmitted. Meanwhile, the majority of groups agreed that screening is useful in preventing cervical cancer. Interestingly, 66%, 86.7%, 75.3%, and 68% of participants in Groups I, II, III, and IV respectively believed that CC is a curse. This adverse belief could contribute to the abstaining of practitioners to advise their patients to undergo screening in 80.6%, as well as explain why the majority of our respondents didn’t perform screening nor receive the HPV vaccine.

The present study findings are consistent with a study conducted in Indonesia, presented that the majority of the female health workers were aware of CC (100%) approximately 97.1% recognized that CC is preventable and 75.7% identified HPV as the underlying cause [24].

The total attitude was observed to be positive and neutral across the four groups. These findings are aligned with the metanalysis study of Chawla B., (2021) who declared a positive attitude about screening in a large proportion of health workers, and 85.47% of participants owned a positive attitude regarding screening [13]. Likely, a study conducted by Daniyan BC et al. (2019) in Nigeria examined the attitude of FHWs toward cervical cancer screening and reported a favorable attitude toward CC screening among FHWs [32].

Regarding study groups’ knowledge and practice of Pap smear; about 46.3% in Group II agreed that screening for CC is expensive. Regretfully, the majority were unaware of the appropriate age for screening and uncertain about what is the best time for undergoing a Pap smear test. While, more than half of the participants in the four groups agreed that a gynecologist is the one who performs a Pap smear, and was knowledgeable about the benefits of a Pap smear. However, the majority of participants in the other three groups excluding physicians were unsure of the pap smear procedure.

Our figures were supported by Obol JH et al., (2021) who stated that most of the participants were aware of the significance of early screening for CC in its prevention, whereas only 16% correctly identified the appropriate age group for cervical cancer screening [29].

The study deduced that the female health workers’ knowledge about the recommended CC screening interval and target population eligible for screening was as poor as documented by two studies held in Nigeria, which stated that pap smears were reported as the most popular screening method and the stratified CC screening knowledge by a cadre of female health care workers, was observed to be ‘profession-dependent’ as doctors were more knowledgeable compared to others [33, 34].

Regarding the preventive practice for cervical dysplasia, most of the professionals had not administered the HPV vaccine (99.5%) nor undergone a pap smear (95.6%). Our observations are replicated in several studies worldwide, which reported similarly low levels of screening among nurses and health workers in Southeast Asia and Africa with screening uptake rates of 16.6%, 15.0%, 18.9%, and 11.4% [27, 35,36,37,38]. In the same context, the study conducted by Eze et al. (2018) in Nigeria, found that just 22% of healthcare practitioners have done a Pap smear and only 28% of respondents who had performed a Pap smear said they had done it more than once. Even fewer healthcare practitioners (11%) had expertise in visual inspection of acetic acid (VIA), with 29% having conducted it more than ten times [38].

The low rate of screening acceptance may be attributed to the fear of receiving a false diagnosis, the discomfort experienced throughout the screening process, and being uncomfortable if investigated by male physicians.

The multivariate analysis of our study elaborated that age and urban residency were independent predictor variables of knowledge level, where the increased participant’s age and being from urban areas were associated with decreased knowledge. Employed as a physician and nurse, earning a high level of education, years of experience, and having a positive family history of cervical disorders, all significantly contributed to increased knowledge level. Likely, Eze et al., (2018) study found that the level of awareness regarding risk factors for CC was associated significantly with occupation, as 70% of doctors successfully identified all risk factors compared to 48% of medical students and nurses, and 36% of midwives [38].

Additionally, Al-Shamlan., (2023) who studied factors associated with the utilization of CC screening among healthcare professionals in Saudi Arabia demonstrated that CC screening was significantly common among professionals who attained a master’s degree or higher. Also, it was higher among HCWs who had a family history of CC. On the other hand, nurses, pharmacists, and technicians were significantly less likely than physicians to utilize cervical cancer screening [39].

Furtherly, our findings are supported by the study conducted by Abebaw E, et al. (2022) in Northwest Ethiopia who demonstrated that physicians had a 2.4 times higher likelihood (adjusted odds ratio = 2.4) of having a positive attitude towards cervical disorder screening compared to other medical professions. Similarly, they found that midwives had a 1.3 times higher likelihood (adjusted odds ratio = 1.3) of having a good attitude than other medical occupations [22].

A prior study involved gynecologists and obstetricians in Egypt reported that less than half of participants (45%) possessed poor-to-fair knowledge, while 57% showed negative-to-fair positive attitudes regrading screening measures and vaccination against HPV, and 44% had ever-done Pap smear and interestingly 45% of physicans had ever advised their patients to take the HPV vaccine [40].

A relevant study conducted by Aggarwal et al. (2023) found that the knowledge about CC screening through a Pap smear was even higher than among our study participants, who included both medical and paramedical staff (97%) and proved to be occupationally dependent [41].

The present study demonstrated barriers against CC screening; for socioeconomic barriers, nearly half of women (58.4%) reported that the screening test isn’t available in their workplace. Regarding healthcare barriers, 72.6% of respondents reported that they didn’t know the health facility that offers screening. For psychological barriers, nearly three-fourths of females (73%) didn’t perform the test as there was no complaint.

Parallelly, a similar study in Egypt reported that the most hindering obstacles for Pap smear testing; were fear of detecting early signs of neoplasia (23.9%) and 17.8% mentioned the test is embarrassing [14].

Previous literature demonstrated a multitude of obstacles to CC screening participation among HCWs including insufficient knowledge, expensive screening costs, fears about misdiagnosis, discomfort or pain felt during screening, varying levels of personal health involvement, gender of the screener, inadequate privacy during screening, and dissatisfaction with the provided health service [31, 40].

Strengths and limitations

The cross-sectional design of this study, suggests a chance of recalling and social desire bias and interfering with the causality relationship. As well, the study was conducted at two health facilities that might hinder generalizability of results. The perception of barriers was based on self-reporting, making it challenging to assess the validity of these answers. On the other hand, the multicentric settings of the study allowed for involving a broad sector of health professional women. The questionnaire arouses the participants’ interest and eagerness to identify more about risk factors, clinical manifestation, and preventive practices against cervical dysplasia.