In this study, we investigated race-based trends in the incidence of metastatic PCa from 2005 to 2021 as well as race-based changes in PSA screening. Although the racial gap in metastatic PCa is narrowing, this occurred against a background of an increasing incidence of metastatic disease in both racial groups. Meanwhile, the PSA screening rate decreased in both racial groups from 2012 to 2020. Initially, NHB men had significantly higher PSA screening rates than NHW men in the early 2010 s (potentially accounting for the narrowing racial gap in the later study period). In contrast, more recent years saw a declining proportion of men undergoing screening with more rapid declines in Black men such as screening rates were no longer significantly different between the two racial groups.

Following the introduction of PSA testing in the late 1980 s and the subsequent widespread adoption of PSA screening in the USA, metastatic PCa rates declined by half from 1988 to 2012 [20, 21]. Our findings indicate that the rate of metastatic PCa decreased in both racial/ethnic groups from 2005 to 2009, but increased from 2010 to 2021. The overall increase in metastatic PCa rates in both racial groups is alarming. Similar to our findings, a recent study investigating the incidence rate of metastatic PCa in relation to the USPSTF recommendations of 2008 and 2012 reported an overall increase in the incidence of metastatic PCa from 2004–2018 with an initial decrease between 2004 and 2009 [12]. Our findings emphasize the continued rise in metastatic disease until 2021. While these trends are likely to be driven by multiple factors, the temporal association with changes in screening recommendations, as well as the high velocity of the change in incidence, strengthen the role of health policy changes, particularly in screening recommendations, as a key factor.

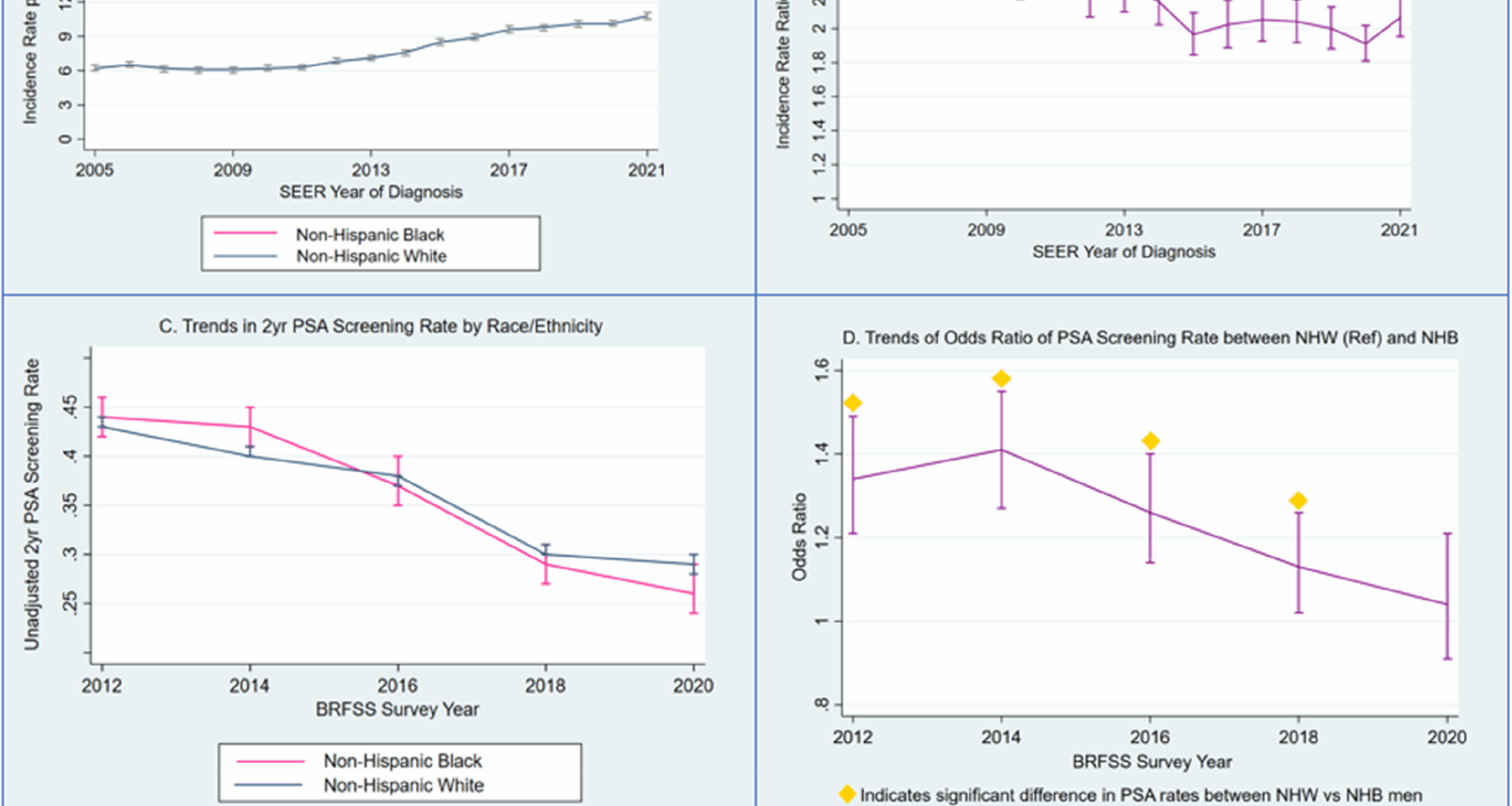

Although an observational study such as this cannot determine causal relationships between race-based trends in screening and metastatic cancer rates, our results help to contextualize the overall trends in both metastatic disease and cancer screening. The incidence rate of metastatic PCa increased in NHB men from 16.4 in 2005 to 22.3 in 2021, while in NHW men, it increased from 6.2 in 2005 to 10.8 in 2021. The incidence rate ratio between NHB and NHW men was 2.6 in 2005, indicating that NHB men had a nearly threefold higher incidence of metastatic PCa compared to NHW men. However, due to the less pronounced increase in metastatic disease among NHB men compared to NHW men, the incidence rate ratio declined over the study period, reaching 2.1 in 2021. Our BRFSS analysis provides critical context for the observed, race-based change in incidence rates and rate ratios over the study period. The earliest screening data from 2012 and 2014 showed higher screening rates in Black men, which may explain the narrowing racial gap in metastatic disease rates observed in the SEER analysis over our study period. Interestingly, in the last three study periods (2016, 2018 and 2020), this trend appeared to reverse, with a more rapid decline in crude screening rates among Black men. Similarly, the adjusted odds ratio of screening among NHB and NHW men from 2012 to 2020 showed significantly higher odds of screening in NHB men in the earlier years, followed by a decline until 2018, with no significant difference in PSA screening between NHB and NHW men in 2020. This suggests that screening declines in the late 2010 s may have occurred unequally by race. Contrary to guidelines that emphasize shared decision-making incorporating patient race [19, 22, 23], Black men experienced greater declines in screening. While these race-based trends have not yet translated into any reversal in the racial trends in metastatic incidence rates, the recent more rapid declines in screening among Black men could foreshadow a widening racial gap in metastatic disease in years to come. Our findings align with a previous analyses of race-based screening rates in the past decade. Kensler et al. reported a decline in PSA screening rates among NHB and NHW men from 2012 to 2018, with a steeper decline in NHB men [24]. A recent analysis from our group examined contemporary trends in PSA screening by race during and after the COVID-19 pandemic [25]. This study, covering 2018 to 2022, showed an initial decline in screening rates for both Black and White patients, followed by a recovery in screening rates. However, the post-pandemic recovery of screening rates was significantly faster in White patients than Black patients. In our study, we found that the incidence of metastatic prostate cancer increased in both, NHW and NHB men, but the gap between these groups narrowed from 2005–2020, as reflected by a steady decrease in incidence rate ratio from 2.6 in 2005 to 1.9 in 2020. However, we observed a sharper increase in metastatic prostate cancer in Black men than in White men from 2020 to 2021, resulting in an increasing incidence rate ratio. We hypothesize that the sharper decline in screening rates from 2012 to 2020 in Black men may have contributed to the sharper increase in metastatic disease. Considering our findings on race-based trends in metastatic disease, the disparity in post-pandemic PSA screening recovery between Black and White [25] men is concerning.

Previous research underscores the importance of social determinants of health when investigating racial disparities in PCa outcomes. A meta-analysis of more than one million PCa patients demonstrated that, when accounting for social determinants of health, Black men with PCa exhibited similar or better survival outcomes compared with White men [4]. Our findings suggest a plausible link between race-based PCa screening patterns and trends in racial disparities in PCa outcomes. It is possible that risk-adapted screening that prioritizes PSA screening in high-risk groups like Black men in earlier years of our analysis may have attenuated the rise in metastatic disease in these groups relative to White men. However, recently ethical concerns have been raised regarding race-based differences in PCa screening recommendations [26]. Current major guidelines that incorporate race-based screening use inconsistent terms such as “Black ancestry”, “African descent”, “African ancestry”, which suggest race as a biologic variable. Treating race as a biologic category for specific screening recommendations carries the risk of obscuring the impact of socioeconomic factors, which are likely the main drivers of poor PCa outcomes [26]. Nonetheless, based on current available literature and consensus discussion in an expert panel, the Prostate Cancer Foundation published Screening Guidelines for Black Men in the USA in 2024. These guidelines recommend risk-adapted screening, starting screening earlier (40–45 years of age) and/or more frequently compared with non-Black men in the USA [27].

Racial disparities in PCa outcomes are not limited to the USA. In the UK, Black men are also twice as likely to die from PCa as White men [28]. As in the USA, evidence from the UK suggests that equal access to treatment eliminates disparities in prostate cancer-specific mortality among patients who undergo treatment [29]. However, analyses of PCa screening disparities between White and Black men in the UK show conflicting results, with some studies reporting higher screening rates in White men and others reporting higher screening rates in Black men [29]. Therefore, screening may not be the primary mediator of racial disparities in PCa outcomes in the UK. This highlights the multifactorial origin of disparities in PCa outcomes in both the UK and the USA.

Several limitations must be acknowledged when interpreting the results of this study. First, and most importantly, we used the SEER database to analyze race-based trends in metastatic PCa. The SEER summary stage represents the stage at diagnosis. If patients are initially diagnosed with nonmetastatic PCa and later develop metastatic disease, they will not be included in this analysis. Furthermore, when PSA screening rates are higher, more men may be diagnosed with nonmetastatic PCa and may subsequently progress to metastatic disease compared to periods of lower PSA testing intensity. It is important to emphasize that SEER data reported in this study reflect metastatic PCa incidence rates at diagnosis only, and therefore, the results do not represent true population-based metastatic cancer rates. Second, the PSA screening data used in this study was based on the national telephone-based BRFSS survey. Certain subpopulations who have less access to telephones or have limited English proficiency may be underrepresented in the survey. However, questionnaires are also available in Spanish and the survey methodology included iterative proportional fitting to weight BRFSS survey data. Third, our analyses included only NHB and NHW patients and did not include individuals from other racial or ethnic groups, who may also experience limited access to screening and worse PCa outcomes than White patients. Investigating screening patterns and outcomes in smaller minority groups is important to inform equitable healthcare strategies. However, we limited our analysis to NHB and NHW men because prior research indicates that NHB men represent a group that is especially disenfranchised and faces unique challenges in access to healthcare [30]. Lastly, we utilized self-reported PSA screening rates in our analysis. Previous studies investigating accuracy of self-reported cancer screening found that self-reported survey data might overestimate cancer screening utilization and indicate racial/ethnic differences in reporting accuracy [31]. However, despite its limitations, BRFSS survey data provide the largest continuously conducted health survey worldwide and offer valuable insights into national health-related risk behaviors and the use of preventive services.