The Stephen A. Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities arrives at Oxford University with a long list of superlatives attached. At 272,300 square feet, the academic hub designed by Hopkins Architects is the largest single building ever constructed by the university, and the largest in England built to the exacting Passivhaus sustainability standard. It also contains the world’s first Passivhaus concert hall. All this is enabled by a record-setting $250 million donation from its eponymous benefactor. It is, then, an emphatic statement of confidence in disciplines such as literature, history, and philosophy, often said to be in crisis, with falling student enrollment worldwide and a diminished voice in cultural debates dominated by technological advances.

This behemoth sits at the heart of the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter—a 10-acre development north of the city center—among sundry small historic buildings and glassy newcomers including Herzog & de Meuron’s Blavatnik School of Government (2015) and the Rafael Viñoly–designed Mathematical Institute (2013). With classical proportions and heavyweight facades of brick and stone, the expansive four-story humanities building takes center stage with calm self-assurance—a solid anchor around which the whole eclectic ensemble now seems to revolve.

The honey-toned Clipsham limestone synonymous with Oxford was a natural choice, says Hopkins partner Andrew Barnett: “We wanted it to be a contemporary building that speaks to the 900-year history of the university.” Composition of the facades draws on a broad lexicon of its buildings rather than any particular period. Round arches and punched windows are neatly incised from planes of butter-smooth ashlar, while roughcast stone lends a hint of the antique, filling blind recesses that avoid a monotonous grid of windows.

The limestone facade was prefabricated off-site. Photo © Hufton + Crow, click to enlarge.

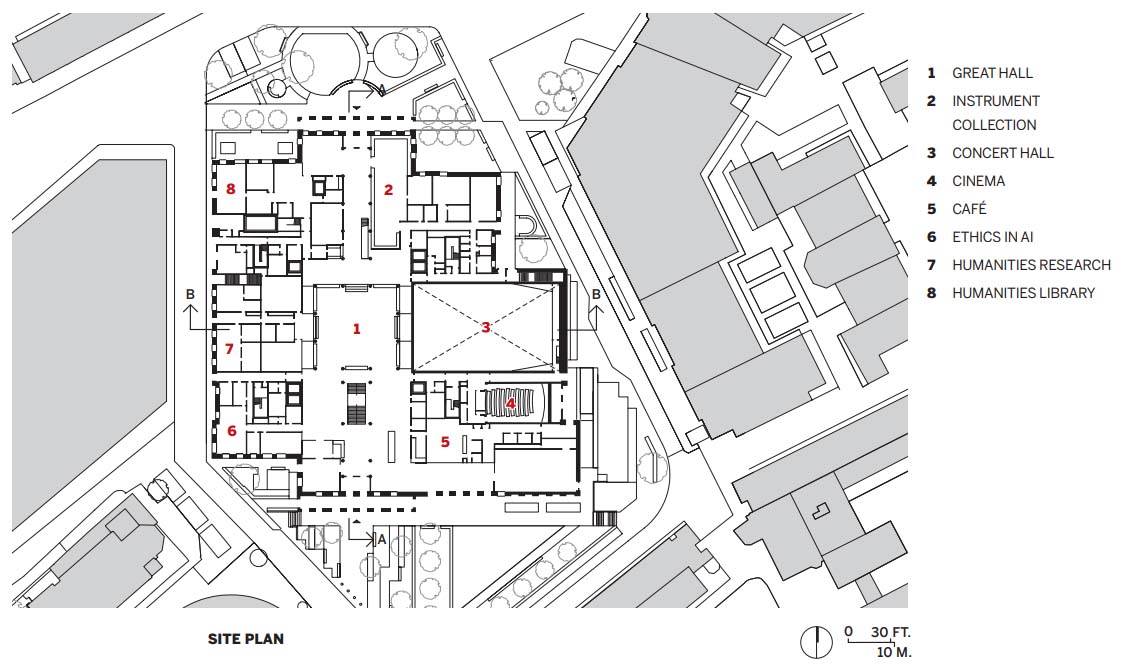

If the sober suiting is safely conservative, the Centre’s organization is a bold break with tradition. Seven faculties and two specialist institutes that were previously scattered across 26 separate buildings are brought together for the first time, with the aim of turbocharging interdisciplinary collaboration. Also integral to the design brief was a revolutionary determination to overturn the separation of “town and gown.” Most of the university’s buildings are gated enclaves wrapped around private courtyards, and the master plan for the Quarter envisaged something along those lines. Instead, Hopkins turned the form inside out. A more compact plan that pulls back from the site boundary, it argued, was the best way to create fertile proximity between faculties, and to draw local people inside.

This has been done to a remarkable degree, and with serious intent. Standing outside in landscaped gardens open to all, Barnett points out that on the two principal facades, three-story pavilions with arched loggias project from the imposing building to create what his clients called a “buggy moment”—thresholds with a more intimate scale, so that a parent with a stroller might feel entitled to cross. Between them, a north–south route through the building follows the most direct line across the Quarter and links a cornucopia of public attractions, from cafés to a cinema.

3

4

A skylit stair (3) and a double-height void (4) provide porosity to the immense building. Photos © Hufton + Crow (1), French+Tye (2)

Entering at either end brings immediate immersion among artefacts of the humanities. To one side of the northern entrance, a glass-walled gallery is filled with historic musical instruments. Looking up, a double-height void gives views straight into the book stacks of the Bodleian library. Ahead, daylight beckons the visitor toward the distant southern foyer, where steps descend to a suite of venues for the performing arts. On the way, the route passes right through the Great Hall, the building’s academic heart.

The four-story Great Hall (above and top of page) is covered by a glass dome spanning 62 feet. Photo © Hufton + Crow

Tesselated triangular timber panels shade the Great Hall. Photo © French+Tye

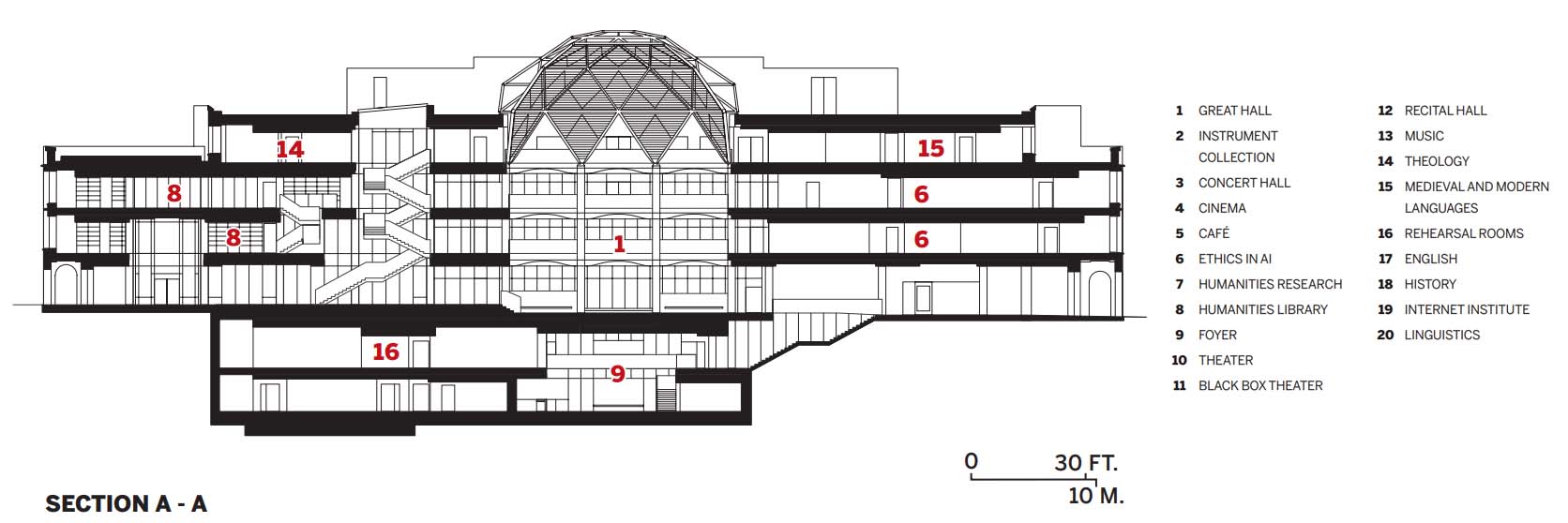

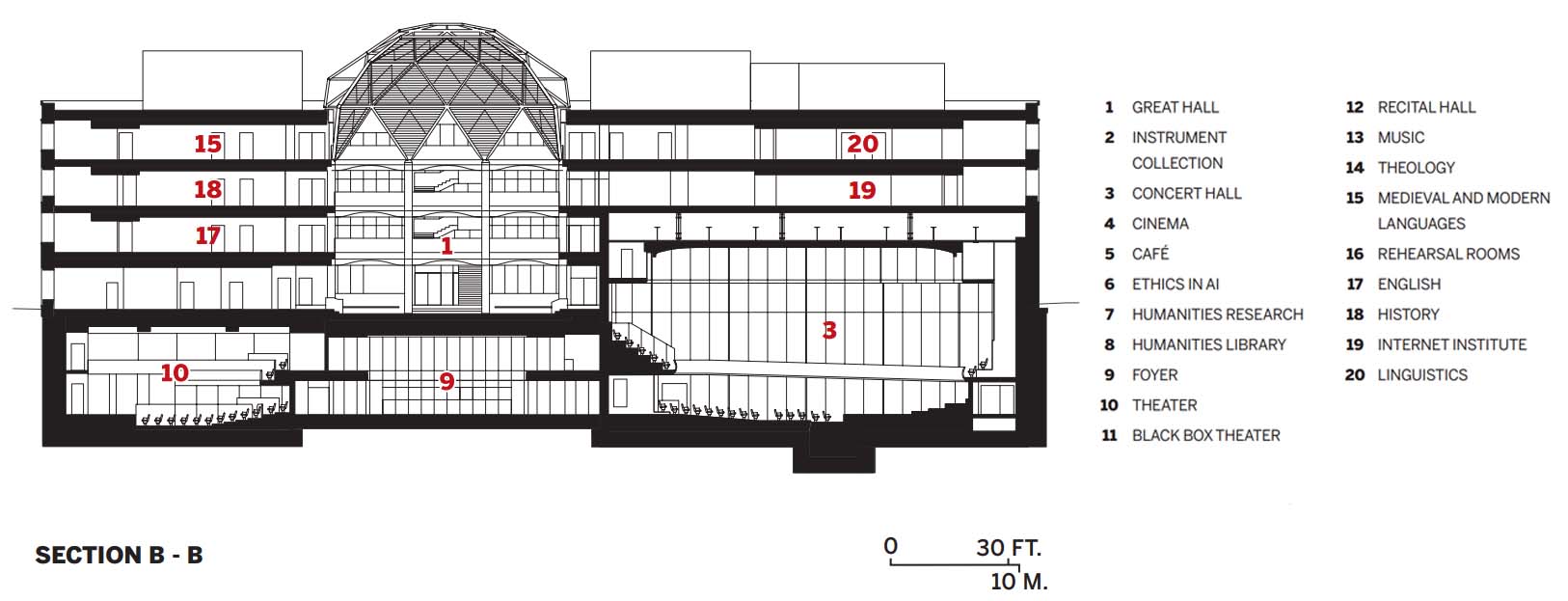

The luminous atrium is a real spirit-lifter. Beneath a glass dome spanning 62 feet, a brise soleil of tessellated timber triangles fans out like the petals of a sunflower. The intricate assembly of engineered components recalls Hopkins’s roots as a pioneer of High-Tech architecture, while texture and warmth are lent by the weighty materials that have also been a long-standing feature of its work. Gently arched precast beams span between chunky columns in low-carbon concrete tinted to resemble the stonework outside. Oak panels line balconies that encircle the space and give access to teaching space on the upper floors.

Each faculty has its own “front door” on the balconies, so that linguists can look across the lively agora to AI ethicists, and musicians to theologians. “Geography matters, when it comes to bringing together different ideas,” says Jennifer Makkreel, Oxford’s deputy head of capital projects. Symbolic gestures underline the importance of these departments. Their entrances sit on the four cardinal points, and in the shape of the hall there are correspondences to Oxford landmarks such as the Radcliffe Camera, a domed 18th-century library with the same dimensions.

Orientation is so intuitive, it’s easy to overlook the complexity of the program that Hopkins has coaxed into coherent order. Overall, the building contains almost 1,000 rooms, and hundreds of small offices cram the outer edges of upper floors. Internally, there are larger seminar rooms and informal spaces where students can work in company; universities are now acutely aware of the need to support mental health and well-being.

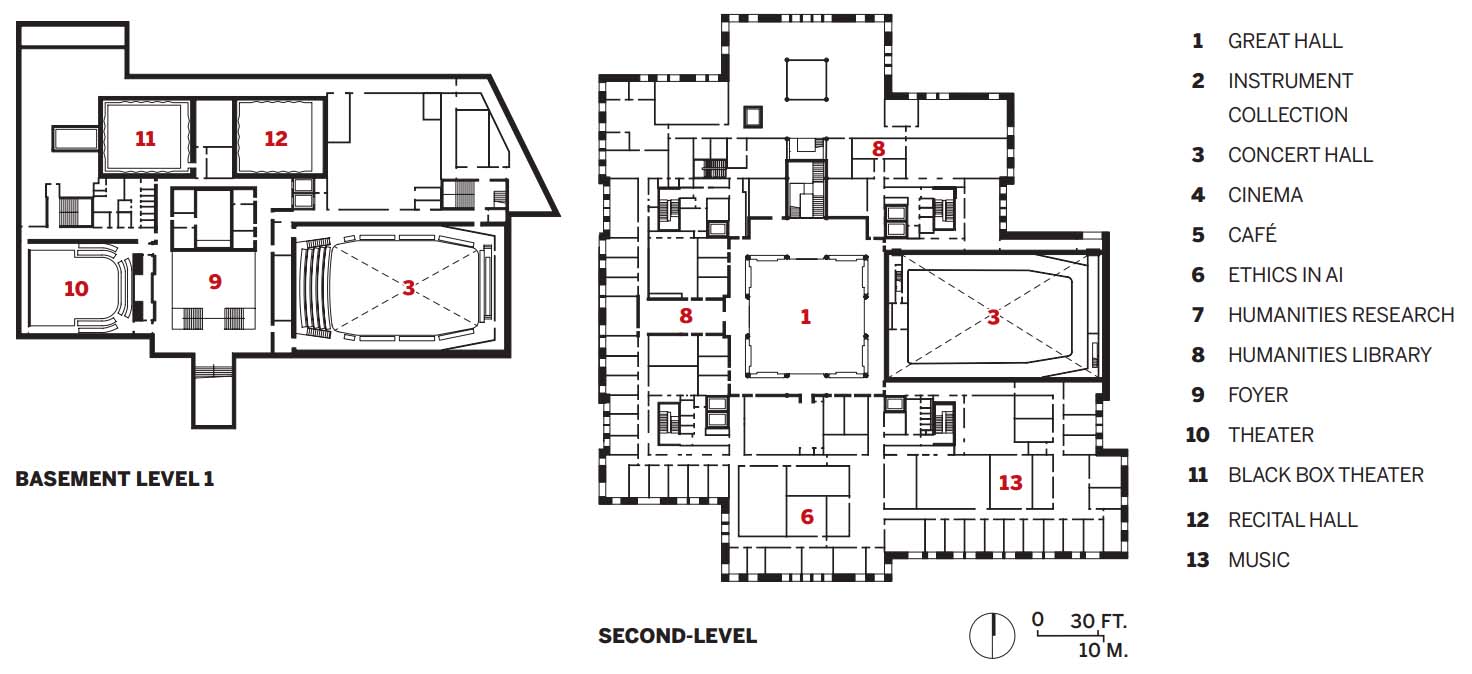

Scale and program made Passivhaus design particularly challenging. Achieving the requisite airtightness was assisted by off-site prefabrication; the entire 59,200-square-foot masonry facade comprises 324 panels, each one story tall and up to 25 feet wide, that went up in just 10 weeks. Large teaching spaces have fixed glazing, but professors insisted that their offices should have operable windows. “In this country, sealing windows is like taking away a human right,” says Makkreel. Digital controls make individual adjustments to the low-energy ventilation system to compensate. In the two-story basement, the design team had to reconcile subterranean superinsulation with the complication of box-in-box theater design.

A foyer for the building’s four performance venues sits directly beneath the grand domed space. Photo © Hufton + Crow

Audiences descend to a voluminous foyer beneath the Great Hall, whose blood-red carpet and wood paneling set the scene for convivial gatherings. Around it, four venues each have a distinctive character. A flexible theater-cum-lecture hall is practical yet stylish, all bent plywood and exposed rigging. A black-walled lab for immersive multimedia events resembles an expensive piece of studio equipment. The 100-seat recital hall next door is an elegant confection of mirrors and white-ribbed acoustic panels. “In terms of facilities alone,” says Barnett, “the music students here are probably the luckiest on the planet.”

5

The venues include a recital hall (5) and a 500-seat concert hall (6). Photo © Hufton + Crow

6

The jewel in the crown is the 500-seat concert hall. Its lozenge shape and lining of scalloped concrete, curved wood, and plush red velvet are engineered to achieve outstanding acoustics, but are also imbued with a feeling of opulence and a character rooted in place. For the 46-foot-high soffit, Hopkins drew on the tradition of heavy timber ceilings in the university’s chapels and libraries with a bent shell of oak that seems to float above the room.

Above the stage, narrow slots in this vault reveal lime-green steel trusses transferring loads from the building above—a rare glimpse of the work required to produce the pervasive sense of ease and composure. “They are the biggest, brightest bits of structure I’ve ever specified,” says Barnett, adding more superlatives to the list.

Size and sumptuous finishes are certainly impressive, but equally important are the building’s subtler qualities: the skillful choreography of welcoming spaces that bring academics into contact with the outside world, and those that will stimulate new thinking about how we live today, enhancing the relevance of the humanities. The opportunity created for students and the city should produce benefits far beyond.

Image courtesy Hopkins Architects

Image courtesy Hopkins Architects

Image courtesy Hopkins Architects

Image courtesy Hopkins Architects

Credits

Architect:

Hopkins Architects — Andrew Barnett, principal; Jonathan Watts, Ernest Fasanya, Chris Bannister, directors; Paul Hunt, Tim Lynch, associate directors; Kitty Byrne, Lily Papadopoulou, senior architects; George Parfitt, architect

Consultants:

Fire Ingenuity (fire); Crown House (m/e); AKT II (structure); Max Fordham (building services, acoustics); Arup (acoustics); CharcoalBlue (theater); Etude (Passivhaus); Gillespies (landscape); Hewshott (IT/AV) CPC Project Services (project management); Arcadis (cost)

General Contractor:

Laing O’Rourke

Client:

University of Oxford

Size:

272,300 square feet

Cost:

Withheld

Completion Date:

September 2025

Sources

Facades:

Vetter, Bryden Wood

Insulation:

Rockwool

Dome Roof Light:

Novum Structures

Windows:

Britplas

Raised-Access Flooring:

Kingspan

Carpet:

Tarkett

Elevators:

Kone, Gartec, Serapid

Acoustic Bearings:

Farrat

Precast Stairs:

Cornish Concrete