A new book celebrates the collaboration between Susan Weil and her husband Robert Rauschenberg, who spent their marriage creating a series of hauntingly beautiful blueprint paper artworksNovember 12, 2025

During a stay at her family home in Outer Island, Connecticut, in 1949, artist Susan Weil introduced her then-husband Robert Rauschenberg to the practice of making cyanotypes – a method of image-making involving exposing blueprint paper to light, using figures and objects to obscure the light and leave impressions on the paper. During the next few years, the pair continued to work together on blueprint artworks. Now, this series of ethereal images of deep and varied blues has been brought together in a new book, The Blueprints of Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, 1952 (published by Stanley/Barker).

8The Blueprints of Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, 1950

Weil had learned to make cyanotypes as a child with her grandmother who, as a young woman, had made self-portraits with the rolls of blueprint paper in her architect father’s office. The tradition was passed down through the family, and Weil and her brother would spend their summers on the island creating blue monochrome vignettes of flowers, shells and other found objects. Years later, when the young married artists spent the summer of 1949 on the island, Rauschenberg was equally captivated by the magical process.

Rauschenberg, who died in 2008, would of course go on to become one of America’s most eminent artists. His explorations into abstract expressionism are credited with having anticipated pop art. Weil, now 95, continues an equally prolific, if less recognised, career as an artist. Her lifelong commitment to art has encompassed painting, photography and experimental pieces in a continual effort to expand painting beyond the two dimensions of the canvas.

The pair initially met while attending the Académie Julian in Paris in the late 1940s. “We were both obsessed with painting – we were really zany painters. We wanted – needed – to paint every minute, all the time,” recalls Weil, speaking to Lou Stoppard in an interview featured in the book. Despite it feeling like “centuries ago”, Weil also remembers the time spent with Rauschenberg on Outer Island and their first experiments with blueprint. “It was something we did for the pleasure of it and the beauty of it. It was the summer break from art school and Bob stayed with my family on their small island. We painted a lot and I talked about my childhood blueprint fun.” Acquiring a roll of blueprint paper from an architectural supplies shop, they set to work making compositions starring Weil’s brother, who, aged three, was the perfect size to fit comfortably on the paper. They surrounded him with seawood and detritus they found on the beach. “We felt like we were exploring something together,” she says.

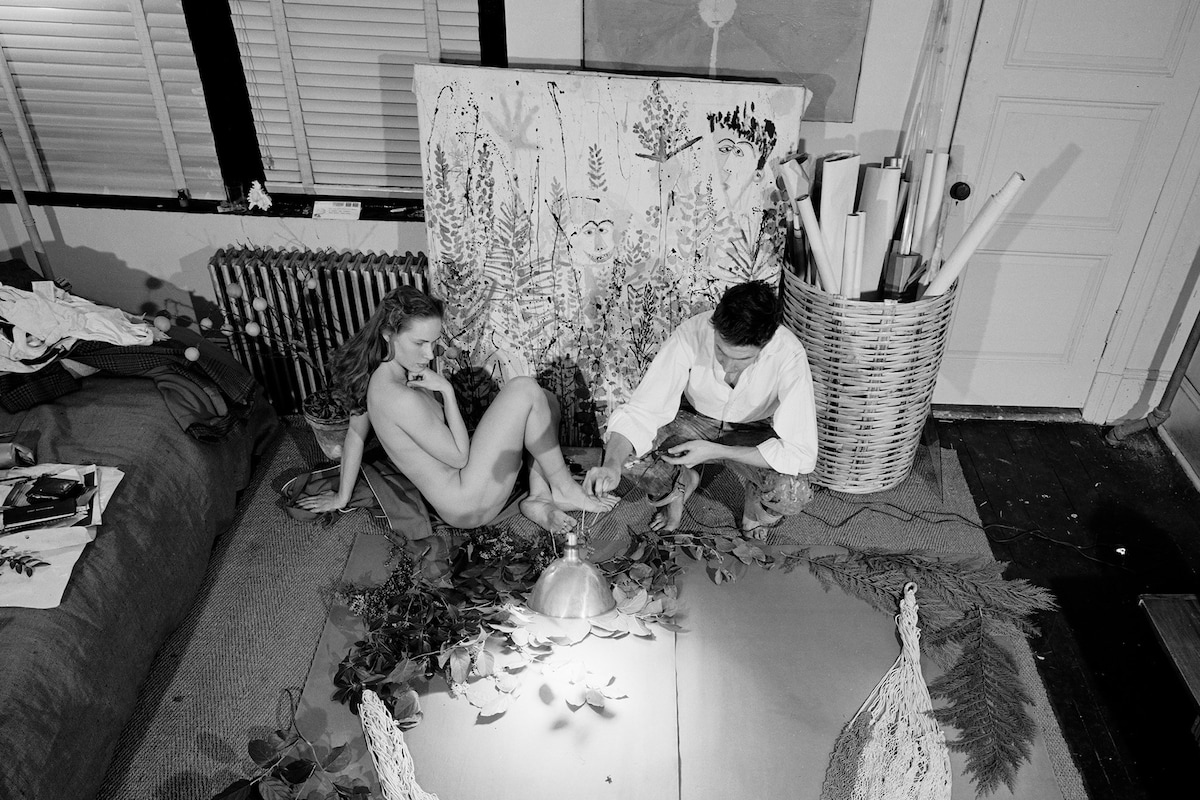

The duo would continue the process when they returned to New York, working on even larger scale blueprints in the garden of their small apartment or inside the shared kitchen and bathroom, using an ultraviolet bulb to develop their pure blue vignettes. For Weil, part of the appeal of the blueprint lay in the potential scale of the artworks – the larger the paper, the larger the images. With big enough paper, it became possible to create full-size images using adults as models. “I really wanted to be very active in my work – and the scale has something to do with that,” she explained. “For all women who were abstract artists, you were investigating your complicated thoughts about being an individual and everything. It wasn’t so simple or direct as being a statement – ‘I want my place in the world’ – but it was about trying to be at one with your own work and take it seriously and have a sense of force.”

Photography by Wallace Kirkland for Life Magazine

Photography by Wallace Kirkland for Life Magazine

The abstract art movement in 1950s New York was a boy’s club, dominated by the archetypal myth of the “avant-garde” male artist. The American modernist painter Hans Hofmann once reportedly paid his student Lee Krasner the dubious compliment of saying, “This painting is so good, you’d never know it was done by a woman.” In the same conversation, he acknowledged Krasner’s huge influence on the work of her husband, Jackson Pollock. It’s an anecdote that perfectly encapsulates the erasure and negation of women from the abstract art world right across the 20th-century. Weil’s works are included in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the J Paul Getty Museum in California, to name a few, yet she has not received the critical consideration of so many of her male peers.

At the time of their marriage, Weil was part of the protest and activism group, New York Professional Women Artists. “I took my work very seriously, and then when people were rough on women, I resented it,” she explains. “I was certainly a big part of the women’s movement when it happened; involved in several groups, and so on … It feels awful. To be not considered because you’re a woman: it’s a very sick thing. It really is. It’s the idea that women are supposed to stay home and take care of the children and the cooking, and that’s what you’re supposed to do … Most people felt that men were the more important makers of the art, and so they chose to focus on the men.”

Photography by Wallace Kirkland for Life Magazine

Photography by Wallace Kirkland for Life Magazine

Rauschenberg’s artistic partnership with Weil had a profound and lifelong effect on the artist, who would continue to use the blueprint technique long after he and Weil separated. He even introduced Jasper Johns to the method. “As I said, the blueprints come from my family, from me, and I resent it when that’s ignored. I do,“ says Weil. “I didn’t mind working with Bob, because it was just something that we were doing for the beauty of it, the surprise of it, but I mind how people look at it afterwards,” she says. “I resent it when it’s ‘Bob’s Blueprints’. They don’t hardly include me, when it all came from me. So that strikes me very badly.”

The Blueprints of Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, 1950 is published by Stanley/Barker and is out now.

Courtesy of the artists

Courtesy of the artists