Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Read more

Malibu, 1977. Martin Scorsese’s mansion is heaving with Hollywood royalty. Brian De Palma’s holding court somewhere. Francis Ford Coppola is there too. Prowling from room to room is Jack Nicholson with that lupine smirk. “I like the setup you boys got here,” he tells Scorsese. “Big speakers for music. A cave for movies and charming the ladies.”

They’ve gathered for drinks before heading to a screening of The Last Waltz, Scorsese’s masterful film about The Band’s farewell concert in San Francisco. But Coppola, concerned by how undernourished Scorsese and his housemate, The Band’s Robbie Robertson, are looking, insists on cooking everyone a proper meal. He hauls a 16mm projector into the kitchen and ingeniously tapes a wooden spoon to one of the reels; his famous Italian sauce will stir itself. Robertson offers to stay behind and watch the pot.

Except, the second the others leave for the film, he slips out to meet his dealer, Jerry. Three-and-a-half grams of pure uncut Colombian cocaine. He lights a cigarette, gets comfortable, loses track of time. Hours pass. When he finally slopes back, Coppola has already returned; a look of thunder is etched across his face. The sauce is spoilt. Robertson discreetly hands Scorsese some coke anyway. “When Francis serves up, we show proper appreciation,” Scorsese cautions Robertson. “He’s deadly serious about his cooking.” So there they sit, jittering, appetites annihilated, forcing down hefty portions of pasta under Coppola’s beady gaze.

This is one of many starry anecdotes coursing through Insomnia, a new posthumous memoir about Robertson’s burgeoning late-Seventies friendship with Scorsese, as it takes root amid a bacchanal. As guitarist and songwriter for The Band, Robertson had helped rewire rock’s DNA, not only as an accomplice in Bob Dylan’s great electric apostasy, but also through his own group’s sepia-toned Americana.

His 2016 autobiography, Testimony, a New York Times bestseller, recounted all this with flashes of linguistic brio. It charted Robertson’s journey from an unconventional Toronto childhood – his mother was part-Mohawk – through his teenage baptism in Ronnie Hawkins’ rowdy rockabilly outfit The Hawks, up to The Band disbanding, torn apart by addiction and fights over money. It was entertaining, certainly, if a little self-hagiographic, his part in The Band’s rise and fall not so much interrogated as carefully curated.

That same spirited storytelling and low-key self-admiration inform Insomnia. While Robertson narrows his focus this time round, zeroing in on the years surrounding the release of The Last Waltz – Scorsese’s concert film featuring cameos by pals such as Dylan, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton, Joni Mitchell and Neil Young – the memoir still positively thrums with humblebrags and namedropping. It was a time when Robertson was becoming more entrenched in the Hollywood community. Having been kicked out by his then-wife Dominique Bourgeois, he’d holed up in Scorsese’s home; the director was himself recently single after an affair with Liza Minnelli had ended his marriage to writer Julia Cameron. Together, they became “some kind of whacked-out new version of The Odd Couple”, mainlining coke and classic films; Robertson recalls them watching Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil. “Marty would let out a small ‘yeah’ or a laugh of appreciation at certain scenes, which pulled me deeper into the whole film experience, almost like seeing it through his eyes,” he writes. “Marty took the time to point out technique in these films.”

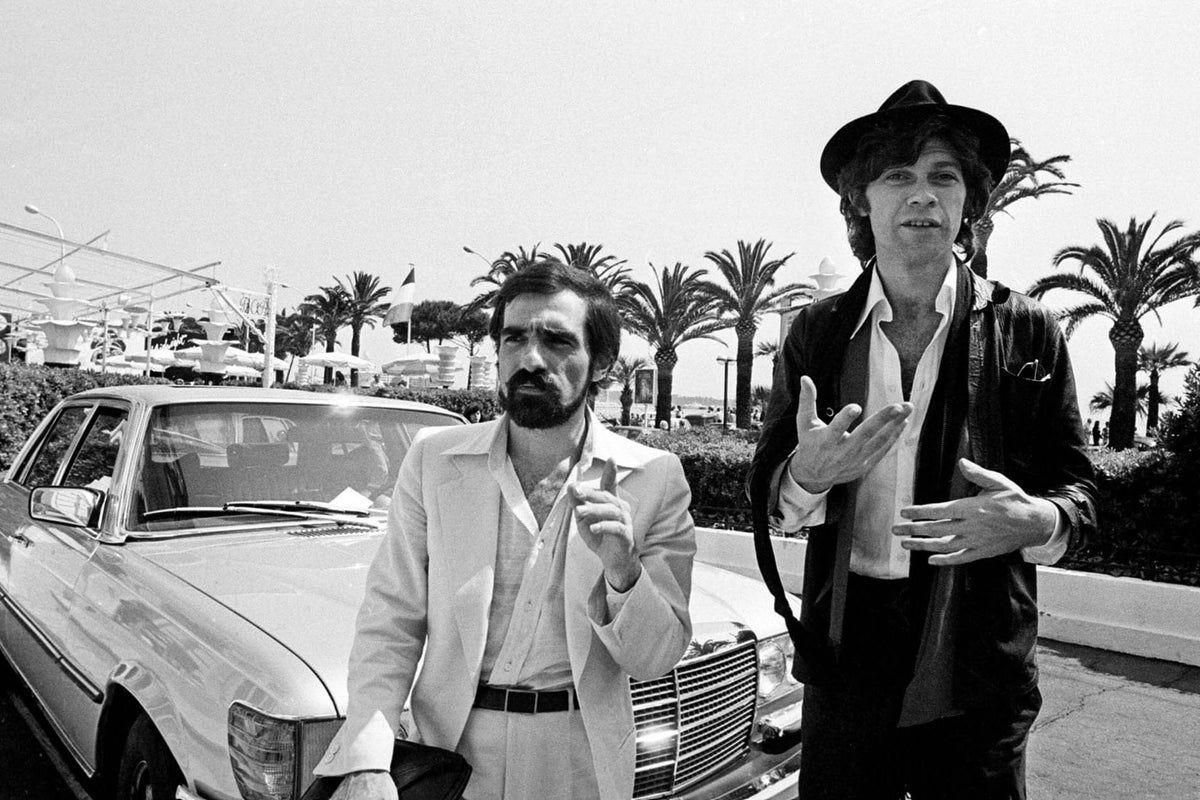

open image in gallery

Blossoming friendship: Robbie Robertson and Martin Scorsese (Redferns/Getty)

If The Band’s slow disintegration had left Robertson “tired of feeling like a babysitter”, burdened at the end by having to write all of their songs, he found the creative fillip he craved in his blossoming bromance with Scorsese. In many ways, it was a hugely successful union. For the next four decades, the two friends would collaborate on the soundtracks for a number of Scorsese’s films, including Raging Bull (1980), The King of Comedy (1982), Casino (1995), The Departed (2006), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) and The Irishman (2019). Shortly before his death at the age of 80 in 2023, Robertson had completed work on the music for Killers of the Flower Moon.

Beyond his very obvious talents as a guitarist and a songwriter, what’s clear in Insomnia is that Robertson had a flair for making friends with the Hollywood elite. Warren Beatty, Harvey Keitel and Gary Busey all make casual appearances. He has multiple hangouts with Robert De Niro, whom he says he “connected with right away. He had a terrific sense of humour and was obviously dedicated to his craft”. Robertson also details his flings with a number of actresses, including Jennifer O’Neill, Geneviève Bujold and Carole Bouquet. On the latter, describing a naked, heated argument between the two of them, he writes: “She pushed me and pounded on my bare chest with the sides of her fist. Her face was flushed as tears flew… I was crazy about Carole, but crazy was the key word.”

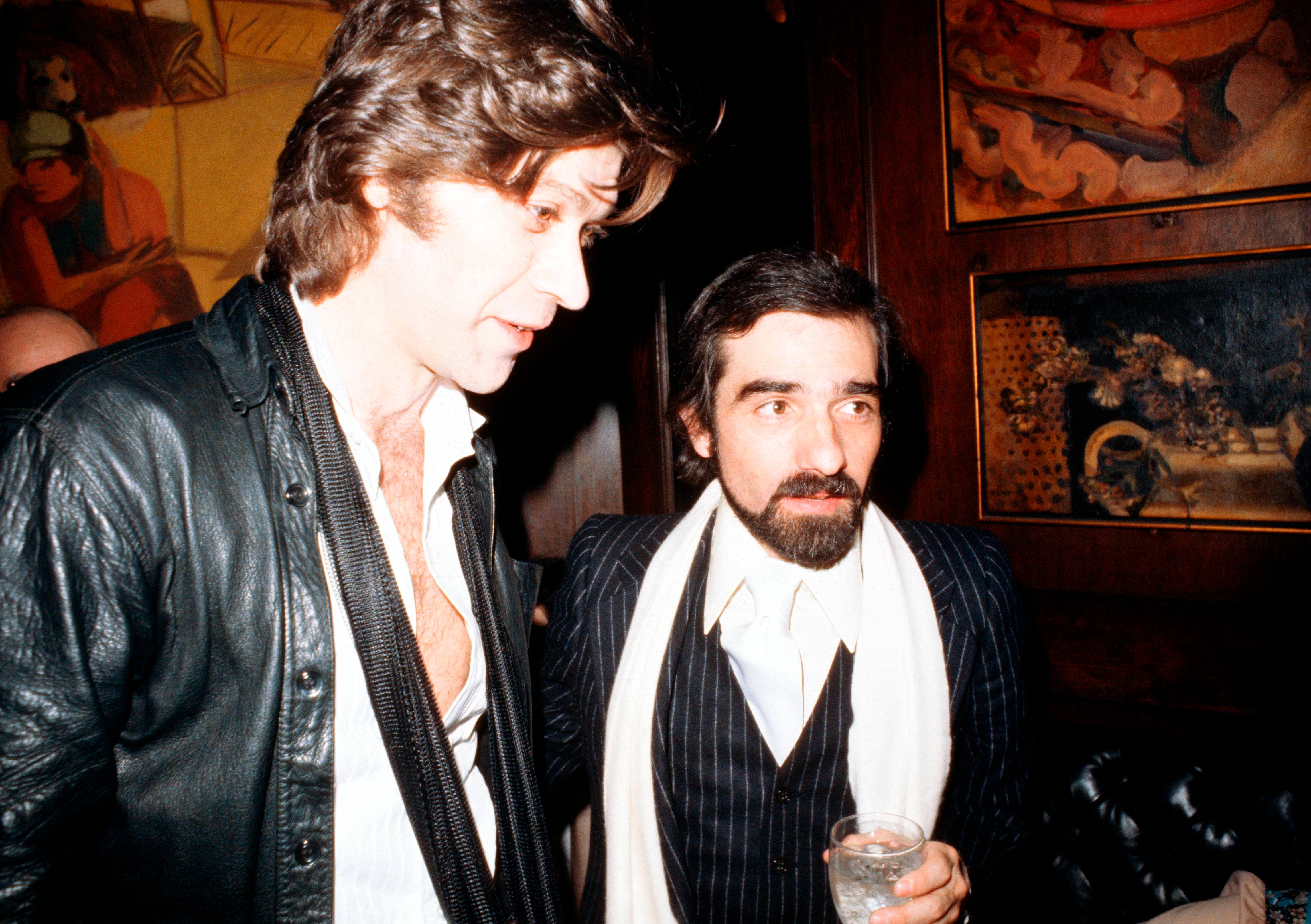

open image in gallery

The Last Waltz: Van Morrison, Bob Dylan and Robbie Robertson during The Band’s farewell show (Getty)

While at the Savoy Hotel, Robertson bumps into Jack Nicholson, in London shooting The Shining with director Stanley Kubrick. Nicholson ends up in his suite with a few friends. “Jack knew how to get the party started,” Robertson writes. “After we passed around a fat spliff, he had us in stitches with stories about Kubrick, who wasn’t exactly known as a barrel of laughs. Jack described shooting what would become the classic scene in the film, where his character, Jack Torrance, having gone completely mad, hacks a hole into a door with an axe to get at his terrified, screaming wife. There was no line in the script for when the character breaks through, but Jack had peered through the hole and ad-libbed the line ‘Heeere’s Johnny!’” Kubrick, Nicholson informed him, usually objected to actors ad-libbing, and was known for shooting many, many takes to get a scene exactly as his vision demanded. “But in this case, Jack told us, Kubrick broke up laughing, and said he intended to use the line in the movie.”

There were times in this period, I thought, when Marty and I both felt that all we had was each other

Robbie Robertson

Robertson casts light, too, on Minnelli and Scorsese’s torrid, drug-fuelled affair, which they had struck up on the set of New York, New York, the director’s disastrous musical. “You could see why Marty was drawn to her magnetism,” Robertson recalls. Visiting the couple in New York, he found their hotel room “somewhat in disarray”, with Scorsese’s assistant dabbing away at “a stain on the rug”. According to Insomnia, there had been a “spat”, which resulted in a glass of wine being launched “through the air and shattering brilliantly on contact with the enormous crystal chandelier, the blood of the grape dripping slowly from the crystals, like a wounded swan”. The couple were immediately over it, “laughing helplessly at the Italian opera they had created”. “I dialled room service and ordered a selection of pastries and more red wine,” Robertson recalls. “The diet of champions.”

Considering all those late-night drug sessions, it’s a small miracle that Scorsese and Robertson ever finished editing The Last Waltz, which was critically acclaimed upon its release in 1978. Robertson’s bandmates were less impressed, though. They felt he had pieced the film together in such a way that they were reduced to his junked-up sidemen. “They weren’t film people,” Robertson claps back, suggesting they should have been “thrilled to work with someone like Marty”.

open image in gallery

‘Mister Hollywood’: Robertson with a young Jodie Foster (Robbie Richardson Estate)

In his own memoir, This Wheel’s on Fire, The Band’s drummer and singer Levon Helm was damning of The Last Waltz. The Arkansas native with the powerhouse vocals feuded with Robertson for years, with Helm adamant that the guitarist had broken up The Band and made off with the songwriting royalties. In Insomnia, alluding to Helm’s heroin habit, Robertson writes: “I was tired of Levon, who was becoming more and more difficult to deal with.”

It’s a shame that Robertson felt compelled to be so cutting about his former bandmate, who died of cancer in 2012, thus giving Robertson the last word. Frustrating, too, is the book’s blackout of Neil Young’s infamous turn in The Last Waltz, during which he allegedly performed with a gargantuan rock of cocaine wedged in his nose. As the legend goes, Young’s manager insisted it be edited out, entailing considerable time and cost. But those are minor quibbles. In Insomnia, Robertson unashamedly leans into the “Mister Hollywood” moniker Helm once disparagingly bestowed on him. More than that, though, this is a paean to male friendship, forged in the furnace of self-medicated heartbreak. “Maybe the rock’n’roll lifestyle I had brought into Marty’s life was to blame for his plight,” Robertson writes of the time, in 1978, when Scorsese was rushed to hospital. “It finally got through to me: I had to stop.” It’s a bracing read, written with enough precision and velocity to keep its more maudlin aspects at bay.

“[Marty] had become my closest confidant,” Robertson notes. “There were times in this period, I thought, when we both felt that all we had was each other.” Unlike The Band, theirs was a relationship built to last.

‘Insomnia’ by Robbie Robertson is published on 13 November by Hutchinson Heinemann