Art

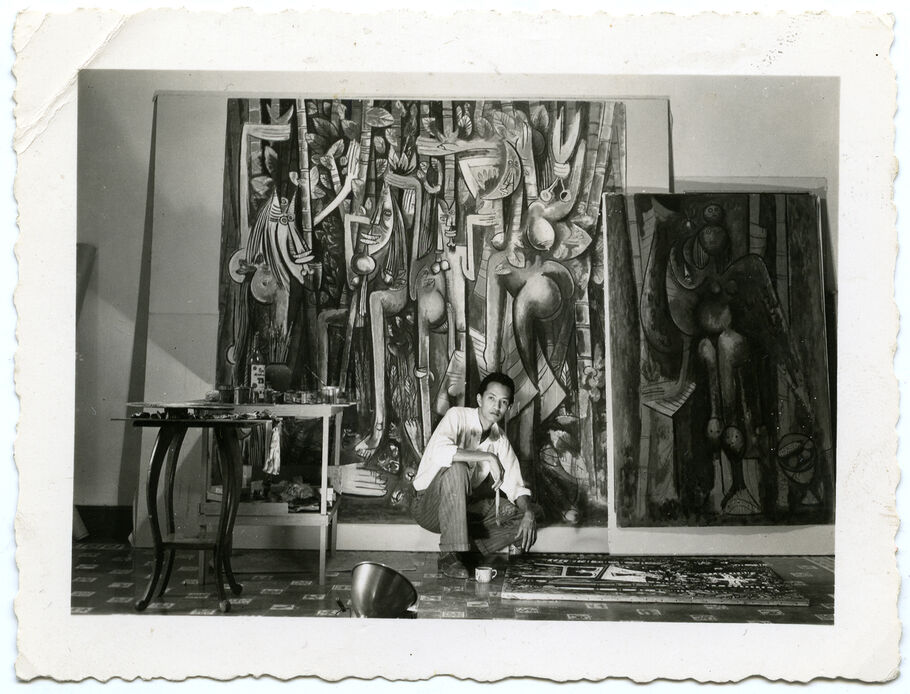

Wifredo Lam with La jungla (1942–43), left, La mañana verde (The Green Morning) (1943), right, and La silla (The Chair) (1943), on the floor, in his Havana studio, 1943. Archives SDO Wifredo Lam, Paris. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Cuban artist Wifredo Lam experienced some of the major social upheavals of the 20th century, both in Cuba and Europe. They all made their way into his restless paintings. Born in Cuba in 1902 to a Chinese father and an Afro Cuban mother, Lam studied painting in Madrid, fought in Spain’s Civil War, worked alongside Pablo Picasso and the Surrealists in Paris, witnessed Cuba on the brink of decolonization, and presented work worldwide during his lifetime. Lam bridged modernism and the Afro Caribbean imagination, transforming Western art with a distinctly diasporic, anti-colonial vision.

Lam is now the subject of a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, “When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream,” on view through April 11, 2026. The exhibition presents more than 150 artworks spanning the 1920s to the ’70s. It offers a sweeping view of Lam’s career, positioning him as a world-making modernist whose work bridged the European avant-garde and the Afro Caribbean imagination.

Wifredo Lam, Installation view of “When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream” at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2025. Photo by Jonathan Dorado. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

Lam moved to Spain in 1923 to train as an academic painter. He spent the better part of the next two decades living in Paris among the avant-garde. However, it was when Lam returned to Cuba in 1941 that he created his most original art. Disturbed by the inequalities of a neocolonial society, he began creating paintings that integrated Afro Cuban iconography and landscape. The artist returned to Europe in 1953, where he lived until he died in 1982.

“There is a fluidity in his work—his figures are always in the process of becoming something else. His forms oscillate between the natural, the abstract, and the human: that makes his work profoundly relevant today,” Christophe Cherix, a director at MoMA, told Artsy.

Here, Artsy spotlights six of Lam’s iconic works on view in the MoMA show.

La Guerra Civil, 1937

Wifredo Lam. La Guerra Civil (The Spanish Civil War), 1937. © Wifredo Lam Estate, Adagp, Paris / ARS, New York 2025. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Painted soon after Lam served with the Republican forces, La Guerra Civil (1937) was his first openly political work. Commissioned for Spain’s pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition—the same show that debuted Picasso’s Guernica—the gouache-on-kraft-paper work compresses the brutality of war into a tangle of masklike faces and limbs.

Lam began the painting while recovering in a sanatorium near Barcelona, where he was sent after falling ill from his work in a munitions factory. From his hospital bed, Lam sketched La Guerra Civil, a 3-meter composition. Made under these precarious conditions, the painting reflects both the violence of war and the strain of his recovery.

In a letter to artist Balbina Barrera, Lam wrote that the painting “is an anti-fascist subject, not very beautiful but very truthful.” Flattened planes and compressed space evoke the chaos of violent struggle. The work stands as early evidence of Lam’s decolonial thinking, where anti-fascism is linked to a rejection of aesthetic hierarchy.

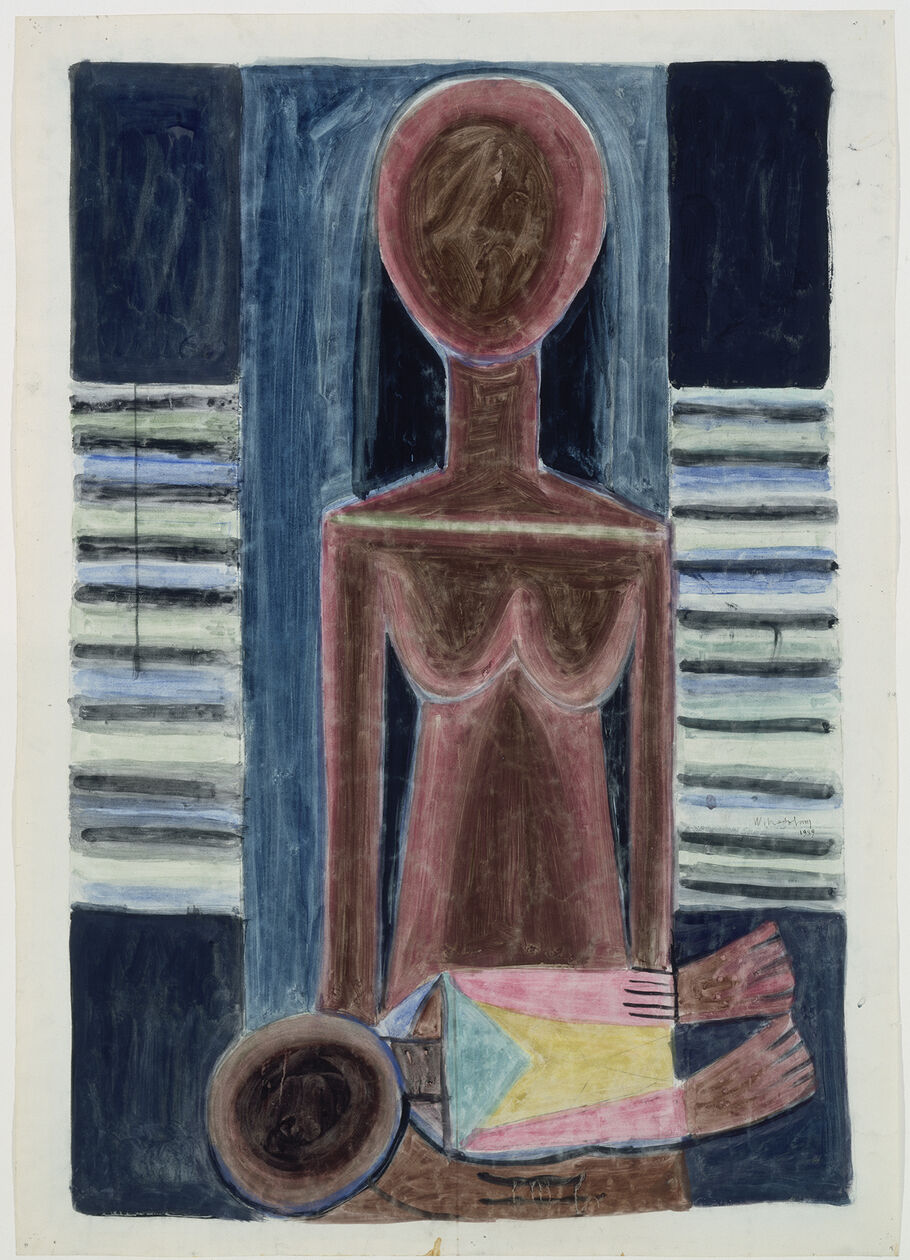

Mother and Child, 1939

Wifredo Lam. Mother and Child, 1939. © Wifredo Lam Estate, Adagp, Paris / ARS, New York 2025. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Lam’s first wife, Eva Piriz, and their son, Wilfredo Victor, died of tuberculosis in 1931. In Mother and Child (1939), a faceless woman cradles a faceless child, rendering Lam’s grief through measured shapes and a muted, restrained color palette.

This work marks Lam’s clear shift away from the academic naturalism he mastered during his studies. By the late 1930s, after years of war, personal loss, and exile, that tradition no longer felt adequate to the world he inhabited. Living in Paris, Lam encountered Picasso and the Surrealists, whose experimentation with form and symbolism opened a new path forward. In this work, the figures are reduced to planes and curves, reaching near-abstraction. This is an early example of the artist solidifying a style of his own. “His work transcended categorization and, by doing so, reimagined and expanded the boundaries of modernism,” Beverly Adams, a co-curator of the show, told Artsy.

Mother and Child was featured in Lam’s first solo show in Paris, at Galerie Pierre in 1939. MoMA’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr Jr., acquired the painting from the gallery, making it the first of Lam’s works to enter any museum collection worldwide.

La jungla, 1942–43

Wifredo Lam. La jungla (The Jungle), 1942-43. © Wifredo Lam Estate, Adagp, Paris / ARS, New York 2025. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Lam created La jungla (1942–43) during his first year back in Cuba. Created with oil paint and charcoal, its life-size hybrid figures stand amid sugarcane stalks. This work, which was acquired by MoMA in 1945, became the defining image of the artist’s career.

Lam painted this work after returning from Europe to his homeland, which was transformed by colonial inequity and racial division. Disturbed by these social realities, he sought to depict Cuba through a language that might properly evoke the country’s spiritual resistance. The result is a dense, vertiginous composition in which limbs, stalks, and masks intertwine.

Lam built La jungla on two sheets of smooth brown paper, which he started using in Europe, where canvas was hard to come by during the war. He sketched the composition in charcoal, then applied thin layers of diluted oil paint (likely mixed with house paint), allowing the surface to absorb drops and splatters, which gives the work its layered, rhythmic depth.

The setting is significant: Sugarcane was central to Cuba’s economy and its legacy of slavery. Lam turns this landscape into a haunted site, where ancestral spirits and colonial ghosts coexist. This scene nods to the rituals of Santería, the African diasporic religion that developed in Cuba, while also reclaiming modernist forms as a technique for the colonized world.

For decades, the painting greeted visitors at MoMA’s entrance. Today, it is a centerpiece of the artist’s retrospective.

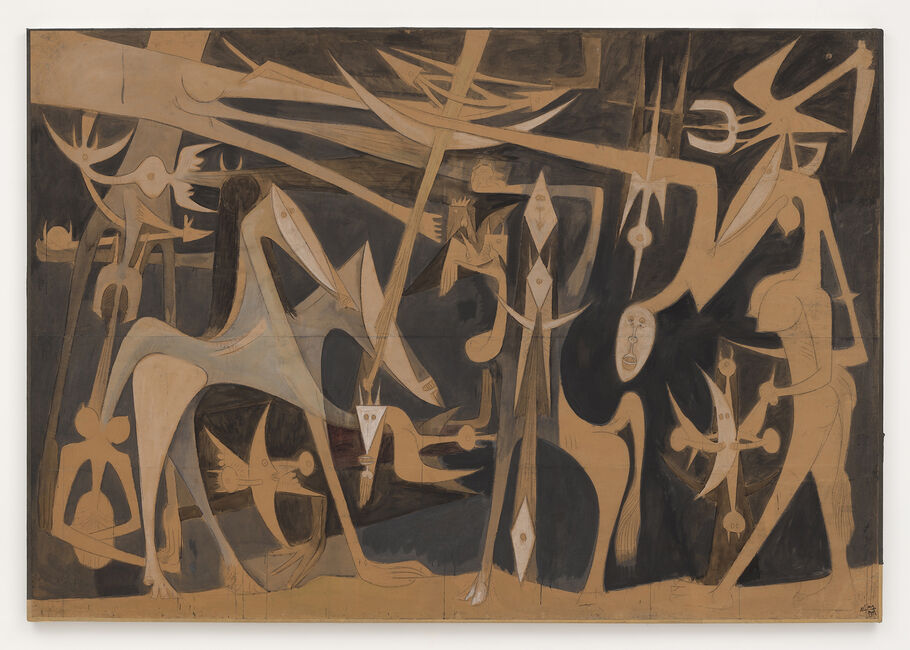

Grande Composition, 1949

Wifredo Lam. Grande Composition (Large Composition), 1949. © Wifredo Lam Estate, Adagp, Paris / ARS, New York 2025. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In Grande Composition (1949), Lam scaled his hybrid figures to mural-like proportions. Painted in thin oil over charcoal on kraft paper, the nearly 10-by-14-foot work was completed during one of the artist’s most prolific periods. “Lam celebrates liberation—its sweeping diagonals and fluid transitions between paint and line echo the momentum of freedom,” the curators noted of the painting in a joint statement.

Created at the close of Lam’s most experimental Caribbean period, Grande Composition is also evidence of his search for renewal for Cuba following the colonial trauma of the 1940s. The familiar hybrid beings of La jungla reappear here as distilled silhouettes. Across the composition, recurring motifs appear—soaring birds, horseshoes, a knife, and the round-headed, horned figure of the spirit Eleguá, guardian of the crossroads. The work’s pared-down palette of ochers, blacks, and browns evokes both the tropical earth and the austerity of postwar modernism. Layers of diluted oil wash across the surface, leaving areas of bare paper visible.

The scale of Grande Composition signaled a new ambition in Lam’s work, anticipating the murals he would soon create in Havana and Caracas, as well as the monumental canvases he used in the 1960s. The work appeared at the inaugural reading of his friend and poet Aimé Césaire’s play La Tragédie du roi Christophe (The Tragedy of King Christophe) in 1963.

Untitled, 1958

Wifredo Lam. Untitled, 1958. © Wifredo Lam Estate, Adagp, Paris / ARS, New York 2025. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Lam painted Untitled (1958) in Albissola Marina, Italy, where he settled after years of moving around. One of six large abstractions from his “La Brousse” series, the work replaces the mythic hybrid forms that defined the artist’s 1940s work with interlocking geometric shapes and sparse use of color. This work, alongside the five others, is inspired by the Cuban manigua, or bush, referring to low vegetation in the Cuban landscape.

These works reflect Lam’s deliberate turn toward large-scale abstraction after a decade of figurative experimentation. “In the ‘Brousse’ paintings from 1958, Lam reimagines the Cuban manigua as both memory and myth, weaving rhythmic patterns of vegetation and movement that evoke a sacred terrain of resistance and rebirth,” Adams and Cherix said in a joint statement to Artsy.

The restless energy of these works reflects the upheaval of a postcolonial world in transition. In a statement for MoMA, Leo R. Douglas, an ecologist, noted that the bush (thickets of vines and low-growing plants) is “actually a product of colonialism itself,” where the “landscape was destroyed and is reestablishing itself.”

By the late 1950s, Albissola had become a gathering place for avant-garde artists and ceramists, and Lam’s experiments with abstraction reflected this new environment. Working among peers such as Asger Jorn and Lucio Fontana, he began to translate the vitality of his earlier figural work into pure rhythmic, formal experiments. These abstractions paved the way for the monumental works of the 1960s and ’70s,

Les Abalochas dansent pour Dhambala, dieu de l’unité, 1970

Wifredo Lam. Les Abalochas dansent pour Dhambala, dieu de l’unité (The Abalochas Dance for Dhambala, the God of Unity), 1970. © Wifredo Lam Estate, Adagp, Paris / ARS, New York 2025. Courtesy of McClain Gallery.

Les Abalochas dansent pour Dhambala, dieu de l’unité (1970) portrays the Afro Caribbean dance for Dhambala, the Vodou serpent deity of unity. Against a dark green background, interlocking figures—human and spirits alike—move in rhythmic procession. These geometric and elongated figures spread across the canvas.

The title refers to the priest of Santería and to Dhambala, whose entwined body with his consort Ayida Whedo symbolizes creation and renewal. Lam’s familiarity with Afro Caribbean ritual was personal: His godmother was a Santería priestess, and during a 1945–46 trip to Haiti with famed Surrealist André Breton, he attended some Vodou ceremonies to better understand the process.

The work uses the same compositional strategies Lam developed in Tropic of Capricorn (1961) and The Third World (1965–66). Here, Lam refines the dense choreography of his earlier paintings into more deliberate structure, reducing his color palette and emphasizing the relationship between line and movement. This shift defined the two decades following his “Brousse” paintings. The geometric scaffolding and flattened planes also reveal the influence of Cubism.

MR

Maxwell Rabb

Maxwell Rabb (Max) is a writer. Before joining Artsy in October 2023, he obtained an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA from the University of Georgia. Outside of Artsy, his bylines include the Washington Post, i-D, and the Chicago Reader. He lives in New York City, by way of Atlanta, New Orleans, and Chicago.