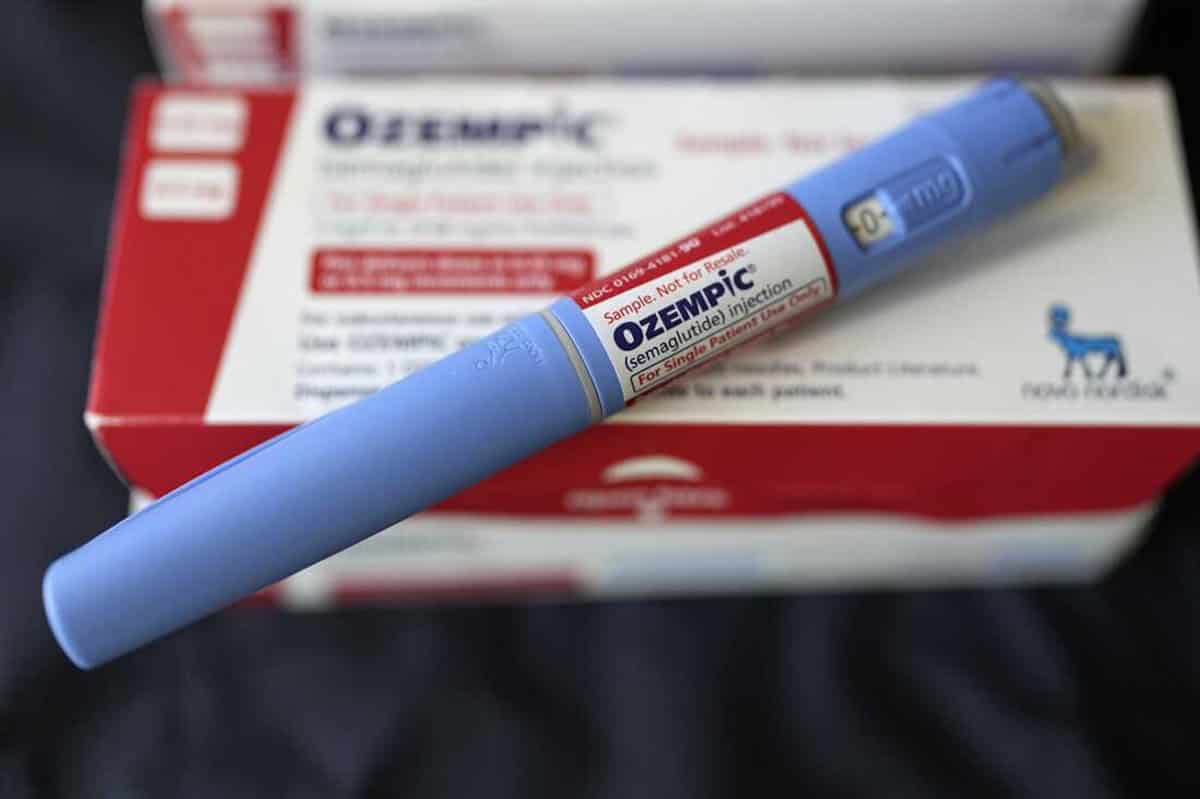

The injectable drug Ozempic. Credit: AP Photo.

The injectable drug Ozempic. Credit: AP Photo.

The story of modern medicine is full of accidental heroes. Penicillin came from a petri dish left open too long. Viagra began as a blood-pressure drug that wandered off in an unexpected direction. And now, the wildly popular GLP-1 drugs — Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro — are revealing a new side to their personality. They may not just slim waistlines. They may help cancer patients survive.

That possibility just became harder to ignore as an increasing number of studies seem to confirm GLP-1 drugs increase cancer survivability.

A new study from the University of California San Diego analyzed medical records from more than 6,800 colon cancer patients across the entire University of California health system. Patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists were less than half as likely to die within five years as those who weren’t on the drugs — 15.5% vs. 37.1%. After adjusting for age, BMI, disease stage, and other health factors, the benefits didn’t shrink.

As lead author Raphael Cuomo explained, “these results are observational,” but they highlight the urgent need for clinical trials to determine whether the drugs truly improve cancer survival.

Multifaceted Medication

GLP-1 drugs are engineered copies of a hormone your gut already makes. After you eat, your intestines release GLP-1 to signal that calories have arrived. It tells your pancreas to release insulin. It slows digestion so your blood sugar doesn’t spike. And it nudges your brain with a gentle suggestion: hey, maybe you’re full now.

Drugmakers took that hormone and built longer-lasting versions of it. That’s how we ended up with medications like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro. They don’t just mimic GLP-1 — they amplify its voice. Food moves more slowly through the stomach. Insulin works more effectively. Hunger fades into the background.

Because GLP-1 receptors aren’t limited to the gut, these drugs end up influencing many systems at once. They interact with brain regions tied to reward. They reshape metabolic pathways linked to inflammation. And they adjust how the body handles energy. In other words, GLP-1 drugs don’t just suppress appetite. They tune some of the body’s most fundamental circuits, which is why researchers are now discovering effects far beyond weight loss.

Scientists have known that obesity and metabolic dysfunction can make cancers more aggressive. Tumors thrive in bodies humming with inflammation and insulin resistance. GLP-1 drugs tamp down both. They improve insulin sensitivity and reduce systemic inflammation. They also lead to weight loss, which itself can shift cancer-promoting pathways.

Some lab studies even suggest GLP-1 drugs may directly mess with cancer cells: slowing their growth, triggering their death, or changing the tumor microenvironment in ways that make survival harder. None of that has been proven in humans yet, but the UC San Diego data adds a new real-world piece of evidence to a fast-growing puzzle.

And related research hints that the effect may not be limited to colorectal tumors. This summer, researchers at the Indiana University School of Medicine and the University of Florida published a massive 15-year retrospective study in JAMA Network Open, tracking 1.65 million patients with type 2 diabetes. The findings were sweeping. GLP-1 drugs were associated with a reduced risk of overall cancer, particularly for endometrial, meningioma, and ovarian cancers.

Another study presented at this year’s American Society of Clinical Oncology involved 170,030 adults with obesity and diabetes in the United States. It found that GLP-1 receptor agonists were “associated with a modestly lower risk of developing fourteen obesity-related cancers, especially colorectal cancer.”

Beyond Cancer: A Drug Class Rewriting Its Own Story

While scientists race to make sense of the cancer findings, GLP-1 drugs are exploding into other unexpected areas of medicine.

Researchers are testing them for alcohol use disorder, opioid addiction, nicotine dependence, even compulsive behaviors. These drug seems to work because they act on the brain’s reward circuits. In early trials and observational studies, people say alcohol becomes less appealing. The cravings lose their edge. Scientists still don’t know exactly why, but many suspect these drugs dull the dopamine spikes that fuel addictive cycles.

There’s also evidence they can help treat heart disease, reduce liver inflammation, and improve fertility in certain patients with PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome). They may even help modulate the immune system in ways still being mapped.

In other words, the GLP-1 story is no longer about weight loss alone.

The Stakes for the Future

If GLP-1 drugs truly help cancer patients survive — if they can prevent certain cancers from emerging — or if they can blunt addiction, reshape metabolic disease, and change the course of chronic illness, then the medical world may be at the beginning of a seismic shift.

For decades, obesity has been treated as a lifestyle failure rather than a biological condition or disease. Cancer risk has been framed as fate. Addiction has been viewed as a moral struggle. GLP-1 drugs are upending those narratives one by one.

But they also raise tough questions: Who will get access? How do we manage long-term safety? What happens when millions of people stay on them for life?

These are the questions medicine now faces. A decade ago, few imagined that a gut hormone analog would become one of the most influential drugs of the century. Today, we’re watching that transformation unfold in real time.