In contrast to the modified Ravitch procedure, the Nuss procedure is a minimally invasive technique introduced by Dr. Nuss in 1998 as an alternative to the modified Ravitch procedure for the treatment of PE, the most common chest wall malformation [1]. For rigid or mixed excavatum–carinatum deformities, several centers now adopt a “sandwich” strategy in which an external compression bar is combined with one or two internal Nuss bars; the original series of 58 patients reported by Park and Kim achieved significant morphologic correction with a < 5% three-year recurrence rate [8]. A recent comprehensive review likewise endorses the sandwich construct as a full-remodeling option for complex or very rigid chests [9], but because our two patients exhibited pure recurrent depression without anterior protrusion, the conventional multi-bar minimally invasive technique was deemed sufficient. Correction of PE not only enhances the cosmetic appearance of patients but also expands the thoracic cavity, which improves cardiac and pulmonary function by relieving anterior compression of the heart by the sternum [4]. For open repair, the risk of recurrence can stem from factors such as incomplete initial repair, undergoing the procedure at a young age, excessive dissection, insufficient support structures, inadequate chest wall healing and premature removal. Although premature strut removal can precipitate early relapse, indefinite retention is not without risk. Case reports describe late strut fracture with cardiac penetration [10] and intrapericardial migration more than 30 years after the index Ravitch repair [11] while biomechanical analyses recommend elective removal within 6–12 months to avoid hardware fatigue and secondary deformity. For patients who undergo primary Nuss repair, issues related to support bars, such as their placement, number, migration, and premature removal, can contribute to failure. Connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome can also complicate this situation and increase the risk of recurrence for both types of PE repair [6]. The approach to the preoperative evaluation for any patient with recurrent PE is similar to that for a patient with primary, uncorrected PE, but with more emphasis on clinical symptoms, including chest pain, respiratory symptoms, palpitations, or exercise intolerance, as well as the patient’s age and psychosocial purpose [12].

Correction of recurrent PE is significantly more challenging and complex than primary repair. In the initial open procedure, irregular fusions and ossifications of the regenerated costal cartilage often create adhesions to the pericardium and lungs, accompanied by dense intrathoracic adhesions between the sternum and mediastinal structures, as evidenced in these patients. Although the Ravitch approach directly reshapes the chest wall through cartilage resection, the presence of a long-retained bar can contribute to similar complications. There is an ongoing debate regarding the optimal surgical approach for patients who have experienced recurrent PE after initial repair [13]. Hebra et al. [14] reported that the Nuss procedure could achieve complete correction of chest deformities only in adult patients with symmetrical pectus defects. Patients with severe asymmetrical deformities and significant calcifications in the regrown costal cartilage should initially be treated using open surgical correction. Liang et al. [13] describe a modified Nuss procedure involving a subxiphoid incision that enables the surgeon to safely dissect the pericardium from the substernal area and allows the bar to pass safely through the mediastinum with the surgeon’s guidance. Cheng et al. [7] further demonstrated the value of this modified, bilateral-thoracoscopy–assisted approach in 96 adults, including six with recurrence after a Ravitch repair, reporting a median operative time of 80 min, minimal blood loss, no cardiopulmonary injuries, and a 91% patient-satisfaction rate. Collectively, these studies support the modified Nuss procedure, which combines a subxiphoid incision and bilateral thoracoscopy as a promising alternative for recurrent PE after open repair. However, Kevin et al. [15] reported that patients with malunion, floating sternum, or significant ossification and deformity required a hybrid procedure using thoracoscopic support bars and sternal elevation, multiple open osteotomies, and chest wall fixation.

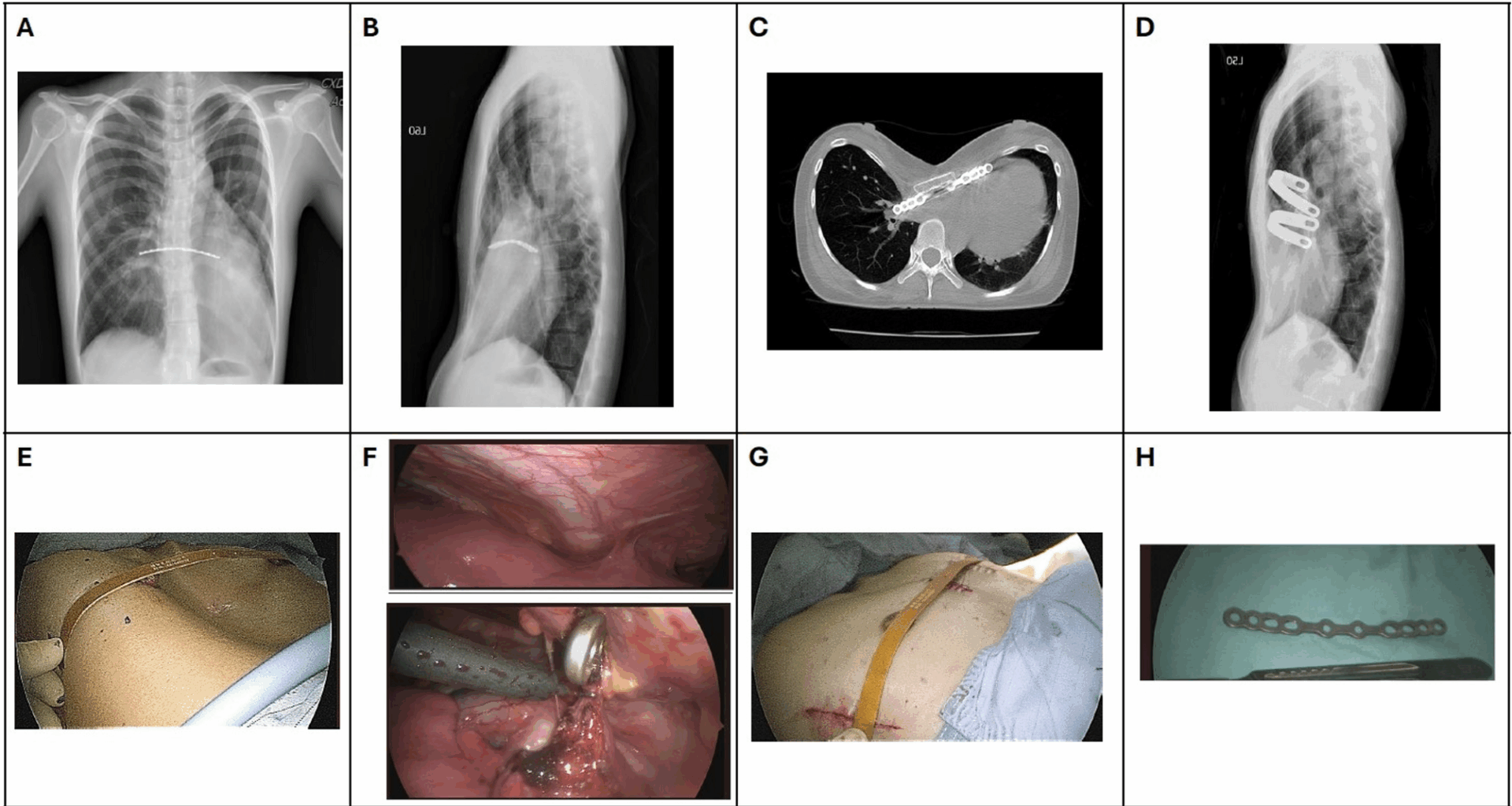

In general, the strut inserted during a Ravitch procedure is intended to be removed approximately 6 months after surgery. In our cases, however, postoperative chest-wall depression persisted, and after consultation with their original surgeon, they elected to leave the strut in place for a longer period. Despite this, only limited improvement was observed over time. In these two cases, we reviewed our institution’s experience with recurrent PE repair and evaluated the effectiveness of the modified Nuss procedure. We decided that the two patients should undergo modified Nuss surgery. Both patients had recurrent PE with worsening clinical symptoms. In patient 1, the prolonged bar retention may have contributed to mitral valve prolapse and moderate mitral regurgitation, underscoring the potential cardiac implications of recurrent or prolonged PE. In addition, both patients had a stainless-steel strut that was retained for >15 years after the modified Ravitch procedure; therefore, we used thoracoscopic guidance to enhance visualization, enabling precise placement of the bars and careful removal of the retained strut. Besides, scoliosis was noted in case 2. Treatment sequencing for combined PE and scoliosis hinges on deformity severity. PE dominance (high Haller index) with a stable Cobb angle < 45° generally warrants chest-wall repair first; severe or rapidly progressing curves (≥ 45–50° or >5–10°/yr) call for spine-first fusion. Reports of post-Nuss curve acceleration and small series of same-day dual repairs highlight the need for tailored planning and close follow-up [16,17,18,19]. Our Case 2 (Cobb 30°, Haller 4.0) therefore, underwent modified Nuss procedure after orthopedic consultation, with radiographic follow-up and a contingency for later fusion should the curve exceed 45° or functional limits emerge [20]. Both our patients underwent a successful modified Nuss procedure, emphasizing its potential as a suitable option in the management of recurrent PE. Postoperative management is important in these cases, with patients undergoing comprehensive pain management, early mobilization, and regular follow-up assessments. Both patients’ cardiac and pulmonary functions improved, as did their psychosocial well-being, after the follow-up. These findings suggest that the modified Nuss procedure can effectively address functional and cosmetic issues in patients with recurrent deformities after the Ravitch procedure, even when the retrosternal bar has been retained for an extended period.