Led by psychiatrist John McGrath from the Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research in Australia, the team examined data spanning 44 years and 11 countries, including the US and the UK. While the findings show a “significant positive association” between cat exposure and schizophrenia, the authors are careful to stress the limits of their conclusions, highlighting the need for higher-quality studies.

This hypothesis dates back to 1995, when researchers began exploring the idea that cats may be carriers of Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that can potentially influence brain function. The parasite, which reproduces exclusively in felines, can also infect humans and has been associated with personality changes and psychiatric symptoms. Though many people are infected without ever knowing, the possible neurological impact of T. gondii remains an active area of research.

As schizophrenia affects how a person thinks, feels, and behaves, discovering possible environmental factors is essential to advancing both prevention and treatment. But even with multiple studies pointing to a link between cat contact and mental health outcomes, the data remains inconsistent and inconclusive.

A Parasite With Unsettling Neurological Links

The primary biological suspect behind the observed correlation is Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that can infiltrate the human brain and potentially influence neurotransmitter activity. According to ScienceAlert, it’s already believed to infect around 40 million people in the US, most without symptoms. Yet once in the system, T. gondii has been linked in some cases to the onset of psychotic symptoms and other disorders associated with changes in brain chemistry.

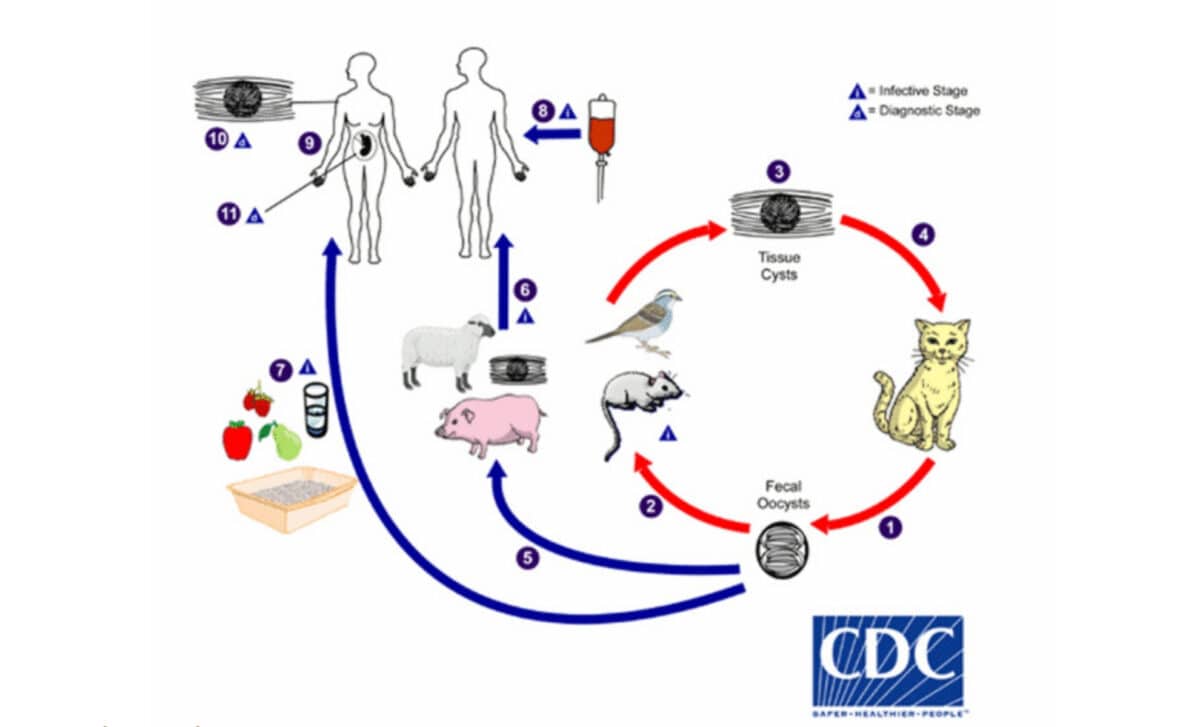

The parasite is commonly transmitted through undercooked meat, contaminated water, or exposure to infected cat feces. Cats, as definitive hosts, can shed the parasite through their waste, making household exposure during childhood a concern raised in several studies. A review cited in the Schizophrenia Bulletin suggests that individuals exposed to cats in early life had about twice the odds of developing schizophrenia-related disorders.

Still, this doesn’t mean T. gondii is definitively the cause. The researchers underscore that while an association exists, causality remains unproven. Other factors could be influencing the correlation, and the source of infection might not always be feline in origin.

Inconsistent Findings and Limited Study Quality

Of the 17 studies reviewed, 15 were case-control studies—a format that can highlight associations but cannot prove cause and effect. According to the authors of the meta-analysis, many of these studies lacked methodological rigor, and some failed to properly adjust for confounding factors that might skew the results.

The review found that only studies of higher quality consistently indicated a potential link between cat ownership and later schizophrenia symptoms. One such study detected no correlation when analyzing general cat ownership before age 13, but a specific time frame—between ages 9 and 12—did reveal a statistically significant association. This points to a possible “critical window” for exposure, but further data is needed to support such a claim.

Meanwhile, other research has failed to find any strong connection. For instance, a US-based study of 354 psychology students showed no relationship between cat ownership and schizotypy scores. However, it did observe that students who had experienced cat bites showed higher scores, hinting at alternative explanations or pathogens.

No Firm Conclusions, but Growing Interest

Despite the widespread coverage of this topic, researchers involved in the study remain cautious. “Our review provides support for an association between cat ownership and schizophrenia-related disorders,” McGrath and his colleagues wrote. But they also emphasize that many of the examined studies were of low quality and call for larger, more representative samples moving forward.

While the findings may alarm some readers, they are not a call to abandon feline companionship. The authors repeatedly caution against making premature judgments, noting that better research is essential before considering any public health guidance based on these results.