Through this study, we aimed to determine whethe a certain ABO blood group is associated with the risk of thyroid cancer. In addition, whether blood groups can affect thyroid cancer extension and metastasis risk.

Overall, blood type O was the most commonly observed blood group, with a prevalence of 47.6% among the population of our study. These numbers align with studies performed in different regions of Saudi Arabia, where blood type O was the most common, with rates of 45.9% and 52%, respectively [17, 18]. AB sample contributed for the lowest number in the sample which also aligns with previous studies where AB Blood group is almost 4% of population [18]. For the Rh status, the majority of the study patients were Rh positive (90%). This is a reflection of the predominant ABO distribution and Rh status worldwide and in Saudi Arabia as well [19].

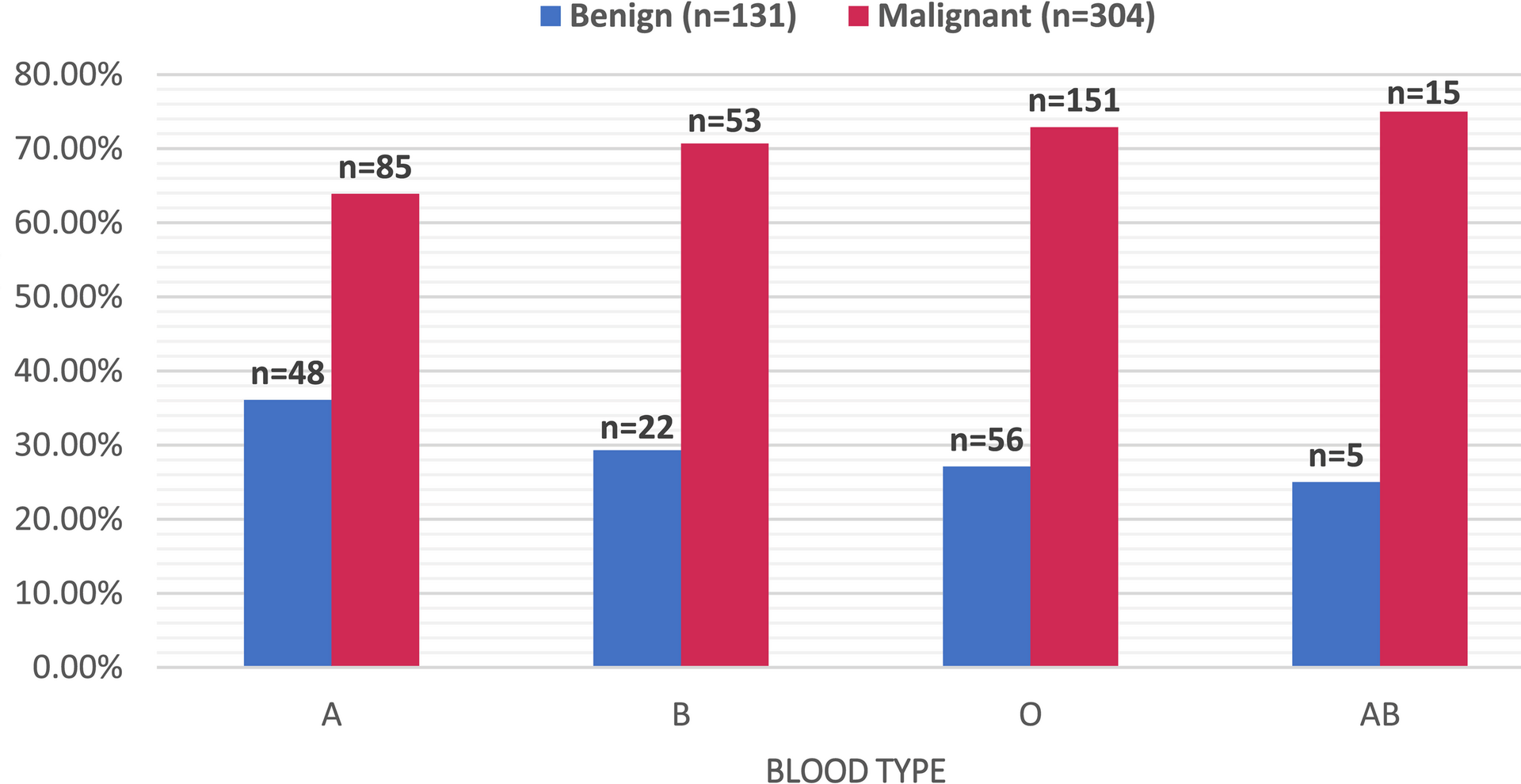

The majority of patients undergoing thyroidectomy in our study had malignant disease rather than benign disease (69.9% vs. 30.1%). These numbers are in accordance with a previous study that highlighted that the positive predictive value for FNA (Find Needle Aspiration) in the diagnosis of thyroid nodules is 78% [20]. In another study, the sensitivity of FNA for thyroid cancer was 68.6%, and the accuracy was 82% [21].

Most patients undergoing thyroidectomy for benign thyroid disease in our study were males. This contradicts previous studies where most benign thyroidectomy cases were females compared to males (79.3% vs. 20.7%) [22]. Another study also showed that in both malignant and benign thyroidectomy cases, females were most predominant [23]. The male predominance for benign nodules in our study may suggest that benign nodules are generally more suspicious in males than in females. Therefore, males tend to be rushed into surgery more often than females.

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of malignancy in either blood type. However, blood group A had the lowest percentage of malignancy compared to other blood types (AB: 75% vs. O: 72.9% vs. B: 70.7% vs. A: 63.9%).

Multiple previous studies have shown a variety of findings [24,25,26,27]. A.H. Mansour et al. found that patients with blood type O tend to have a higher risk for thyroid cancer (as well as lymphomas and gastric cancers) than any other type of cancer [24]. Hui-xian Yan et al. found that AB blood was more frequently associated with malignant than benign thyroid nodules [25]. Others, such as Shahrokh et al. and Meiling Huang et al., found that blood type B was more associated with the risk of thyroid cancer [26, 27]. All these different findings can raise the conclusion that blood type does not predict the risk of malignancy or the benign nature of the disease.

However, in regard to aggressiveness, metastasis risk, and extrathyroidal extension, we observed a link between blood type AB and follicular subtype, larger tumour focus size, capsular invasions, vascular invasion, and distant metastasis. Our result show that the highest ratio of positive lymph nodes was observed in blood type AB. Blood type AB consistently demonstrated a pattern of more aggressive pathological features, including higher rates of vascular and capsular invasion, a larger tumor size, and a greater ratio of positive lymph nodes. Although these associations did not remain statistically significant after Bonferroni correction—likely due to the small sample size of AB patients—they reflect a coherent biological trend across multiple indicators of tumor aggressiveness.

These results are in line with other research findings of Tam Abass et al., who showed that individuals with blood type AB had a higher prevalence of positive lymph node involvement than blood type B [23]. However, the same study highlights that blood group B exhibited a poorer overall prognosis, which partly opposes our findings [23]. Another study also suggested that cervical lymph node metastasis plays a role in predicting future distant metastasis [28]. Therefore, finding the factors that correlate with higher risk of lymph node spread, including blood groups, can in turn aid us in avoiding the risk of distant metastasis.

On the other hand, Gaube Alexandra et al. found that individuals with AB blood type had a higher risk for oral cavity cancer [29]. Additionally, Khushboo Singh et al. found that having blood type B is a potential risk factor for having laryngeal cancer [30]. The lack of further studies to support what blood type is more associated with higher aggressive behaviour prompts the need to look at this topic. Our study findings that the AB blood type has more extrathyroidal extension raise the question of whether patients with the AB blood type should undergo prophylactic lymph node dissection with other markers to be defined.

It was also observed in our results that although insignificant, blood type O does have lower rates of capsular invasion and the lowest ratio of positive lymph nodes. This finding is in accordance with other studies on different types of malignancies that also found that blood type O has a better overall prognosis in ovarian, nasopharyngeal, and pancreatic cancer [31,32,33,34].

With regard to benign pathologies, our study suggests an association between blood group B and the development of autoimmune conditions such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and autoimmune thyroiditis. Tam Abass et al. and Younus et al. both reported a higher prevalence of thyroiditis among individuals with blood group O (57.3% and 52%, respectively) [23, 35]. Several studies suggest that AB. Several studies suggest that ABO blood type antigens may be associated with a general inflammatory response [36,37,38].

In addition, Younus et al. also reported that individuals with blood type AB could be protected against Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which agrees with our study results in which none of those with blood type AB developed Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [35]. While there has been some interest in the relationship between blood types and autoimmune illnesses, further studies are needed to confirm these relationships. Nonetheless, our data imply that certain blood types may pose a risk of being protective against the development of thyroiditis and might be used as a risk stratification tool in clinical practice.

Regarding other factors, our findings show that younger age at diagnosis is associated with increased capsular invasion. This aligns with recent evidence in a 2024 study, Wang et al. reported significantly higher rates of thyroid capsular invasion (43.0% vs. 33.1%; p = 0.001), alongside larger tumor size and more frequent lymph node involvement in younger patients compared to older adults, suggesting a distinct biological behavior in younger patients [39].

Strengths and limitations

Considering that the area of this topic is much in research and few papers have discussed the role of blood type in determining the aggressiveness of thyroid cancer as much as papers have addressed other cancers, this paper sheds new light on this topic. While, prior studies largely explored cancer risk and prevalence by blood group, our study examined a wide range of aggressiveness indicators along with that. These indicators included tumour size, lymph node involvement, and invasion. The Statistical methodologies employed also helped correct and adjust study findings ensuring an accurate interpretation.

However, as this is a single-centre study conducted in a tertiary centre it may not reflect the findings on a broader sample. In addition, as the data collection was carried out retrospectively, some information could have gone missing through documentation. The retrospective design limits the ability to control for unmeasured confounding factors. Moreover, a larger sample size which could ensure a higher percentage of rare blood groups such as AB blood group would make the statistical power stronger. We also had no control or specific reporting of extent of thyroidectomy and lymph node dissection which would have shed new findings in the study.