Reconstructing periocular and eyelid defects is a complex and multifaceted challenge that requires a careful balance between functional restoration and aesthetic outcomes. The periocular region is not only critical for protecting the ocular surface, but it also plays a significant role in facial expression and appearance. As such, any reconstructive effort must address both the structural integrity of the eyelid and the cosmetic concerns of the patient. In this study we aimed to systematically review the findings from a wide range of studies, highlighting the various surgical techniques available, their outcomes, and the challenges associated with periocular reconstruction. By thoroughly exploring the various flap techniques and reconstruction methods following the tumor excision, as well as the challenges in periocular reconstruction and advances in surgical methods discussed among the included studies in our review, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of periocular reconstruction and its future directions.

Common flap techniques, indications, and applications by defect characteristics

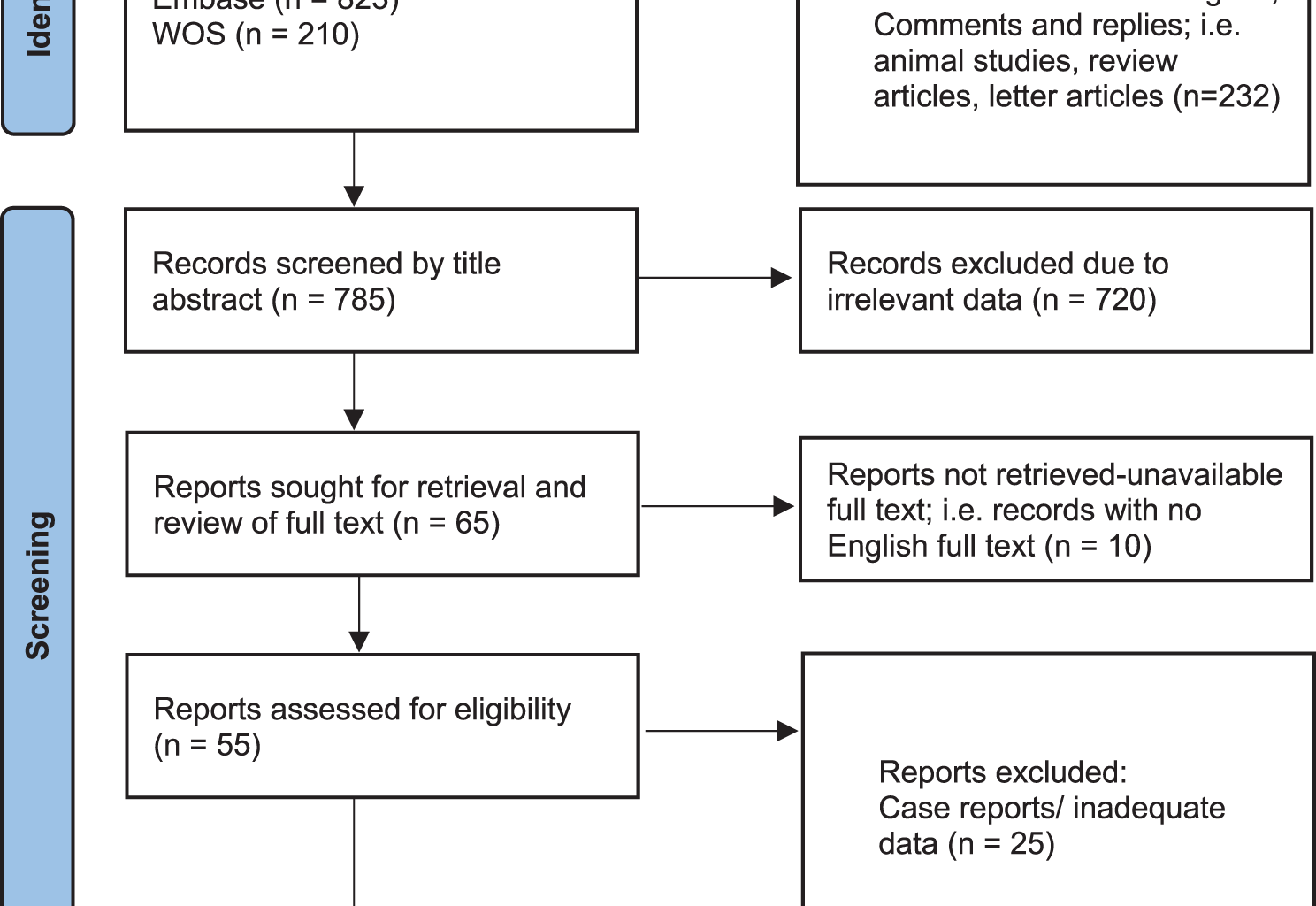

Flap techniques are among the most commonly used methods for periocular reconstruction, offering versatile solutions for a variety of defects. The choice of flap depends on the size, location, and depth of the defect, as well as the patient’s anatomical characteristics and aesthetic goals. Over the years, several flap techniques have been developed and refined, each with its own set of advantages and limitations [24]. Based on our cross-analysis of flap utilization (Table 3), distinct patterns emerge that guide clinical decision-making. For defects in the upper and lower eyelids (40.40% of cases), the Mustardé cheek rotation flap was the most prevalent (141 cases), particularly for medium-sized defects (10–20 mm), due to its ability to mobilize adjacent cheek tissue for seamless integration and minimal distortion of the lid margin [24]. Similarly, the modified rhomboid flap (125 cases) (Figs. 5, 6) excelled in small-to-medium oval defects ( < 15 mm) by aligning closure tension with natural lid anatomy, reducing risks like ectropion or lagophthalmos [17]. In contrast, large full-thickness eyelid defects ( > 20 mm, often > 50% eyelid width) favored the Hughes tarsoconjunctival flap (50 cases) (Fig. 7), which provides essential posterior lamellar support and high patient satisfaction rates (up to 90% in long-term follow-ups), though it may require a two-stage procedure [9, 18]. This is particularly indicated in post-BCC excision (828 cases overall, the majority etiology), where Mohs surgery ensures clear margins but leaves substantial full-thickness gaps [18].

Hughes flap technique for lower eyelid reconstruction; A Preoperative view of the lower eyelid defect. B Elevation of the tarsoconjunctival flap, maintaining vascular supply. C Transposition of the flap into the lower eyelid to reconstruct the posterior lamella. D, E Bipedicle flap from the upper eyelid transposed to restore the anterior lamella of the lower eyelid. F Final postoperative result showing both functional and aesthetic restoration of the lower eyelid

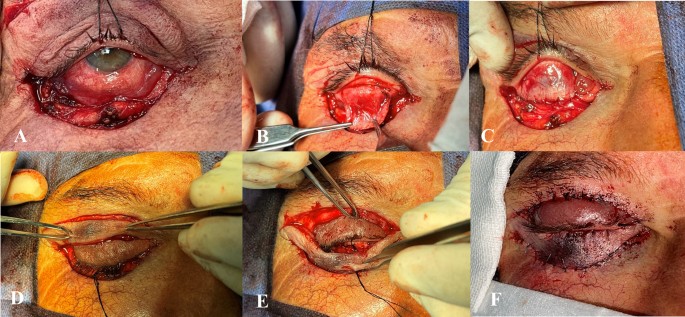

For medial canthal defects (36.75%), the paramedian forehead flap predominated (109 cases) in medium-to-large sizes (13–25 mm), offering robust vascularity ideal for oncologic reconstructions post-BCC excision with orbital involvement, as it minimizes recurrence while preserving aesthetics [28]. Bilobed flaps (40 cases) (Fig. 8) were effective for medium defects (10–20 mm) in areas of limited tissue laxity, preventing webbing and dog-ear deformities through refined angular designs [13]. Propeller variants, such as the LOOP flap (30 cases), addressed larger ( > 20 mm) or complex defects with superior mobility and single-stage efficiency, achieving excellent functional outcomes without necrosis in reported series [14, 20]. Nasal/perinasal defects (7%) typically involved smaller sizes ( < 15 mm) and utilized perforator-based flaps like supratrochlear (20 cases) for multi-subunit coverage with reliable blood supply, or nasolabial flaps (15 cases) for minor sidewall repairs [21, 31]. In other areas (e.g., orbital or temporal), advancement flaps like Tenzel (60 cases) were versatile for variable-sized defects, particularly 1/3–2/3 eyelid involvement, emphasizing single-stage simplicity [24]. This location- and size-specific pattern highlights the importance of tailoring flaps to defect characteristics: rotation/advancement types for eyelid preservation of function, and axial/perforator flaps for canthal/nasal optimization of vascularity and aesthetics. Such insights, derived from over 1,200 aggregated cases, underscore the evolution toward patient-centered selections, though heterogeneity in size reporting limits direct comparisons and calls for standardized metrics in future studies.

Double bilobed flap; A Preoperative scar deformity involving the medial canthus and tear-trough region. B Intraoperative view following elevation and rotation of the double bilobed flap. C Immediate postoperative appearance. D Result at 10 days, demonstrating restored contour

Outcomes, complications, and risk factors

Functional outcomes are paramount in periocular reconstruction, particularly in maintaining eyelid stability, protecting the ocular surface, and ensuring proper eyelid movement. Techniques such as the advancing tarso-conjunctival flap and hinged tarsal flap have demonstrated excellent functional results, with minimal complications and preserved eyelid contour [2, 4]. Aesthetic outcomes are equally critical, as poor cosmetic results can lead to significant psychological and social distress. Flaps such as the PMFF and nasal root island flap offer excellent color and texture matching, with scars concealed within natural expression lines [11, 28]. Studies emphasize the importance of long-term follow-ups to evaluate the durability of outcomes. Gunnarsson et al. [21] reported high satisfaction rates with perforator-based flaps, while Ang et al. [28] demonstrated PMFF efficacy over a follow-up period extending up to 23 years. These findings validate the longevity and resilience of these techniques in maintaining both functionality and aesthetics.

Despite advancements, complications remain a concern, though our analysis shows they were minor in 95% of cases and often manageable with conservative measures or minor revisions (Fig. 4). Tip necrosis was the most frequent (13.5%), predominantly in rotation flaps like Mustardé for larger defects ( > 20 mm) or those with compromised vascularity, resolving conservatively in 80% of instances [24, 28]. Ectropion occurred in approximately 10% of lower eyelid reconstructions, correlated with tension mismatches in medium-large defects, but mitigated by modifications like dermal pennants or tension-free closures [5, 6, 29]. Wound dehiscence and epiphora were also common (each ~8–10%), with higher epiphora rates (15%) in medial canthal flaps due to lacrimal system involvement, particularly in BCC cases with orbital extension [1, 4]. No significant correlations were found with defect location overall, but invasive tumors (e.g., aggressive BCC) showed elevated risks (e.g., 20% higher necrosis in orbital invasion cases) [1, 20]. Risk factors include defect size ( > 20 mm), patient comorbidities (e.g., smoking affecting vascularity), and technique selection; preoperative Doppler imaging or staged procedures could reduce necrosis by 20–30% [12, 28]. Other issues like hypertrophic scarring or conjunctival overgrowth were rare ( < 5%) and addressed via scar revision or monitoring. From a patient-centered perspective, satisfaction was high (85% in studies with > 6-month follow-up), with minor complications rarely impacting quality of life, emphasizing the need for informed consent on these risks [9, 21, 29].

Advances in techniques and novel approaches

Advances in understanding facial anatomy, particularly the vascular supply, have led to the development of more versatile and reliable flap techniques. Perforator flaps, which are based on consistent anatomical structures in the facial region, have revolutionized periocular reconstruction. These flaps, including the nasolabial flap and forehead flap, provide excellent vascularity and flexible design options, allowing for extensive reconstructions with minimal donor site morbidity (Fig. 9). The supratrochlear flap, a well-established axial flap, exemplifies the versatility of perforator flaps. It can pivot on either the angular or supratrochlear artery, providing increased rotational freedom and making it particularly useful in the periorbital, nasal, and periocular regions [21, 31]. Gunnarsson et al. [21] highlighted the advantages of perforator flaps, noting their ability to achieve superior anatomical subunit replacements with aesthetically pleasing results. These flaps have proven to be reliable, minimally invasive, and effective in single-stage outpatient procedures, with high patient satisfaction and minimal complications. For instance, in cases where a large defect involves both the nasal sidewall and the medial canthus, the supratrochlear flap can be used to reconstruct both areas simultaneously, providing a seamless transition between the nasal and periocular regions.

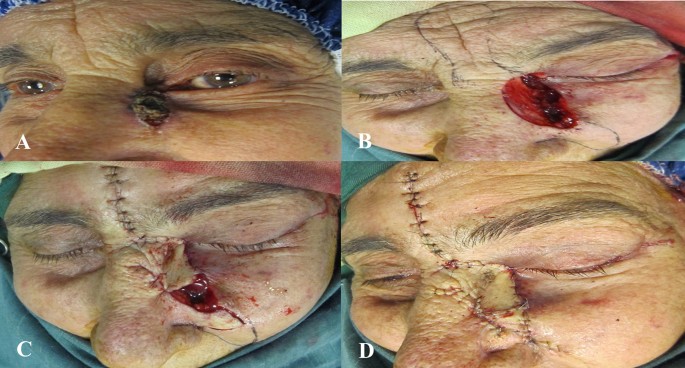

A Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the medial canthus involving the upper and lower eyelids. B, C Tumor resection followed by reconstruction using the tenzel procedure with a periosteal flap. D Defect repaired with a glabellar flap and a nasolabial flap

Another innovative flap technique is the lateral orbital orbicularis propeller (LOOP) flap [14], which has shown promise for periocular reconstruction, particularly for extensive defects in the upper and lower eyelids. The LOOP flap is based on a non-axial orbicularis oculi pedicle and provides reliable coverage for large defects. In a study of 44 cases, no flap necrosis occurred, and minor complications such as trichiasis and scleral show were manageable. The LOOP flap’s reliability, ease of use, and excellent cosmetic and functional outcomes make it a valuable option for periocular reconstruction. For instance, in cases where the defect involves both the lower eyelid and the malar region, the LOOP flap can be used to provide extensive coverage without the need for additional grafts or flaps [14]. For upper eyelid reconstruction, the Cutler-Beard flap has been a traditional method [32], but it has significant limitations, including the lack of structural support for the posterior lamella, which can lead to entropion and ocular irritation (Fig. 10). Hsuan et al. proposed a modification to this technique, utilizing a free tarsal graft and a skin-only lower eyelid advancement flap (Fig. 11). This approach avoids dissection of the orbicularis muscle, leading to reduced disruption of the lower eyelid and faster healing. Notably, this method reduces the period of eye closure to two weeks, compared to the traditional 4–8 weeks, and has demonstrated good vascularization and minimal complications. The modified Cutler-Beard flap offers faster recovery and better functional and cosmetic outcomes than traditional approaches, with only one case of mild ectropion observed in the study. This modification represents a significant advancement in upper eyelid reconstruction, particularly for patients who cannot tolerate prolonged eye closure due to occupational or personal reasons [19]. Recent studies have introduced novel approaches to address specific challenges in periocular reconstruction. For example, Ko et al. [26] evaluated the flip-back flap technique for eyelid defects ranging from 5 × 18 mm to 15 × 25 mm. This technique involves creating a semicircular myocutaneous flap rotated 180 degrees to fill the defect. The study reported high success rates, with no cases of flap necrosis and satisfactory functional and cosmetic outcomes. The flip-back flap is particularly suited for patients with limited excess periocular tissue or those who have undergone previous reconstructive procedures. Nasiri et al. [5] focused on preventing ectropion, a common complication following lower eyelid reconstruction. The study introduced a modified nasojugal flap with a dermal pennant, which improved contour transition from the lower eyelid to the zygoma and prevented ectropion. This technique was particularly effective for large lower eyelid defects, offering better functional and aesthetic outcomes compared to traditional methods (Fig. 12).

Cutler-Beard flap technique for upper eyelid reconstruction; A, B Preoperative upper eyelid defect requiring reconstruction. C, D Elevation of the lower eyelid flap and advancement through the created bridge to the upper eyelid defect. E Postoperative appearance following flap placement

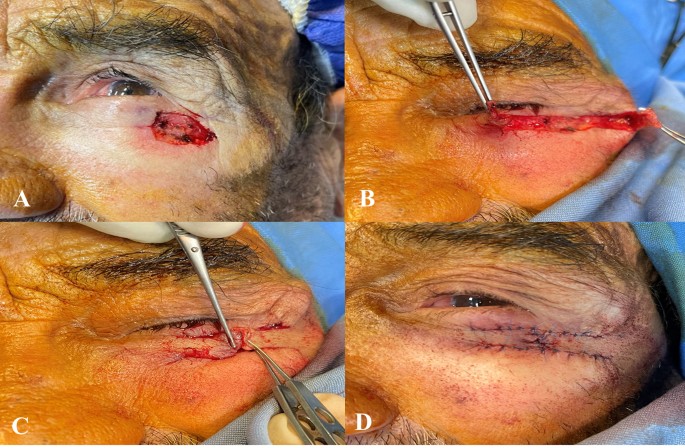

Advancement (sliding) flap technique; A Preoperative view of the defect requiring reconstruction. B, C Elevation and advancement of the local tissue flap to cover the defect while maintaining vascular supply. D Immediate postoperative appearance after flap inset, showing tension-free closure and preserved function

Nasojugal flap technique; A Preoperative view showing the lower eyelid lesion. B The defect following excisional biopsy. C Flap elevation and transposition performed with preservation of vascular supply. D Immediate postoperative appearance and E postoperative day 10 outcome following reconstruction with the nasojugal flap

Albanese et al. [27] evaluated the modified cheek advancement flap (MCAF) for reconstructing defects in the medial lower eyelid, infraorbital cheek, and nasal sidewall. The MCAF was found to be highly effective in preventing complications such as ectropion and provided excellent long-term aesthetic outcomes. The study emphasized the importance of eyelid tightening and the absence of horizontal incisions, making the MCAF a reliable option for medial periorbital reconstruction. Zhou et al. [10] introduced SMAS-pedicled flaps for reconstructing small- to medium-sized facial defects. These flaps, based on the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS), offer robust vascularization and flexible design options. The study demonstrated that SMAS-pedicled flaps provided aesthetically favorable outcomes with minimal donor site morbidity, making them a valuable option for post-traumatic and post-excisional facial defects. Berggren et al. [33] investigated blood perfusion in upper eyelid flaps, comparing myocutaneous and cutaneous flaps. The study found that myocutaneous flaps, which include the orbicularis oculi muscle, had significantly higher perfusion than cutaneous flaps. This finding suggests that myocutaneous flaps provide superior vascular support, allowing for longer flap designs and reducing the need for free grafts. Rana et al. [30] presented a novel approach for managing lower eyelid retraction using a buccal fat pedicle flap combined with a delayed tarsoconjunctival flap. This technique effectively restored eyelid height and contour, with no major complications reported. The buccal fat pad’s robust vascularity and accessibility make it a promising option for reconstructive oculoplastic surgery. Furthermore, Gąsiorowski et al. [29] reviewed 167 cases of eyelid reconstruction following malignant tumor excision. The study evaluated various techniques, including forehead flaps, Mustarde cheek flaps, and local flaps, and found that these methods yielded satisfactory functional and aesthetic results. Complications such as ectropion and flap necrosis were observed but showed no significant correlation with tumor location or reconstruction technique.

For more complex defects, particularly those involving orbital invasion or extensive tissue loss, advanced techniques such as extended orbital exenteration and propeller flaps have been developed. Kovacevic et al. [20] explored the use of extended orbital exenteration for advanced periocular skin cancers with orbital invasion. In their study of 21 patients, the galea-skin flap was used for primary reconstruction, achieving clear surgical margins in 85.7% of cases. Patients reported satisfaction with the aesthetic appearance, although complications such as necrosis of a frontal flap and orbitocutaneous fistula were observed. Propeller flaps, introduced by Rajak et al. [8], have also emerged as a versatile option for periocular reconstruction, particularly in cases where local tissue availability is limited. In their study of 8 patients, Rajak et al. demonstrated that propeller flaps could achieve excellent cosmetic and functional outcomes for lower lid and medial canthal defects (Fig. 13) [8, 20]. For extensive defects, PMFF has been a cornerstone in medial canthal and lower eyelid reconstruction. Agarwal et al. reported favorable outcomes with PMFF, preserving functional vision in 77.8% of patients, though minor asymmetry was noted due to bulk-related factors [12]. Similarly, Ang et al. [28] found that ipsilateral PMFFs minimized glabellar bulkiness while maintaining adequate vascular supply, reducing the risk of flap necrosis. Comparative analyses of flap techniques further highlight the trade-offs between different reconstructive approaches. The cheek rotation and advancement flap provided effective coverage for periocular defects, though ectropion risk necessitated careful intraoperative positioning. The Limberg flap, with its versatile design and minimal donor morbidity, was well-suited for small-to-medium defects, whereas the forehead flap, despite its two-stage requirement, remained indispensable for extensive reconstructions. The Mustardé lid switch flap was particularly beneficial for upper eyelid reconstructions, balancing functional and aesthetic outcomes (Fig. 14). However, split-thickness skin grafts, though useful for large defects, posed challenges such as contour mismatches and a higher incidence of postoperative dryness [24].

Tenzel flap technique for lower eyelid reconstruction; A Preoperative view of the lower eyelid defect. B, C Marking and elevation of the semicircular rotational flap, preserving vascular supply. D, E Final postoperative result showing restoration of eyelid contour and function

Mustardé flap technique; A Preoperative appearance of the lower eyelid lesion. B Resulting defect after excisional biopsy. C Elevation of the rotational cheek flap, maintaining vascular integrity for optimal healing. D Flap inset and suturing, restoring both function and aesthetic contour of the eyelid

Another significant challenge in periocular reconstruction is managing scleromalacia, a rare but serious complication of periocular surgery that can lead to persistent epithelial damage and scleral thinning. Traditional approaches, such as grafts using allogenic sclera or cornea, have limitations in terms of availability and cosmetic outcomes [15]. Han et al. [15] introduced Ologen, a biodegradable collagen matrix, as an adjuvant to conjunctival flap surgery. This combined approach has shown superior results, particularly for smaller defects, although severe cases of scleromalacia may still present challenges. For instance, in cases where the scleral defect is deep and involves impending perforation, the use of Ologen may not be sufficient to achieve optimal cosmetic outcomes, and additional surgical interventions may be required. One of the most common benign conditions requiring surgical intervention is xanthelasma palpebrarum, a yellow plaque that typically appears at the medial canthus. Simple excision of large lesions can lead to complications such as ectropion or lid retraction [7, 34]. Elabjer et al. [7] demonstrated the effectiveness of a single-step or sequential excision using lid skin grafts combined with local flaps for large xanthelasmas. This approach minimizes complications and provides a more aesthetically pleasing outcome, particularly in settings where laser treatment is unavailable. For example, in resource-limited settings where laser technology is not accessible, the use of local flaps and skin grafts can provide a cost-effective and reliable alternative for managing large xanthelasmas. In cases of aggressive BCC with orbital invasion, traditional management has involved orbital exenteration, which is a disfiguring procedure that removes the orbital contents and surrounding structures. However, Madge et al. [1] proposed globe-sparing surgery as a less disfiguring alternative. In their study, this approach demonstrated a low recurrence rate (5%) and preserved visual acuity in 85% of patients, although complications such as epiphora and extraocular motility restrictions were observed. Despite these challenges, globe-sparing surgery offers a viable option for carefully selected patients, emphasizing the importance of balancing oncologic safety with functional and aesthetic outcomes. For instance, in cases where the tumor has not invaded the orbital apex or the optic nerve, globe-sparing surgery may be a feasible alternative to exenteration, allowing patients to retain their vision and avoid the psychological impact of losing an eye.

Limitations, patient-centered perspectives, and future directions

Despite the advancements in periocular reconstruction, several limitations remain. Heterogeneity in study designs, outcome measures, and follow-up periods complicates the comparison of techniques. Additionally, many studies are retrospective and lack long-term follow-up, limiting the ability to assess late complications and recurrence rates. Future research should focus on prospective, randomized controlled trials to directly compare the efficacy of different techniques and establish standardized protocols for periocular reconstruction. While our broad scope captures real-world variability (e.g., similar flap preferences across etiologies but higher complications in invasive BCC cases), it highlights the need for sub-group analyses in future reviews. Patient-centered perspectives emphasize high satisfaction (85% overall) when techniques align with individual goals, such as minimizing downtime or preserving vision [1, 9, 21]. Emerging directions include integrating AI for vascular mapping to predict complications and developing bioengineered flaps for enhanced predictability.