In this study, we explored, for the first time in Brazil, the population genetic structure of two sympatric bat species, Pteronotus personatus and Pteronotus gymnonotus, both cave-dependent taxa. Our findings indicate that in the Caatinga drylands, P. personatus was restricted to four bat caves, whereas P. gymnonotus was more widely distributed, occurring in all surveyed caves. Despite these differences in occurrence, both species exhibited relatively homogeneous levels of genetic diversity and no clear evidence of population structuring. For P. personatus, we observed only weak signs of genetic differentiation among caves, which were not clearly associated with geographical distance across analyses, suggesting that while some differentiation may be emerging, gene flow still occurs among caves, maintaining overall connectivity. In contrast, P. gymnonotus cave subpopulations showed high levels of connectivity even across large distances. Importantly, no hybridization was detected between the two species, underscoring their distinct genetic identities.

Bats of the genus Pteronotus are cave specialists, exhibiting a strict relationship with their roosts [9, 30]. They typically select caves with high climatic stability, low air circulation, and high temperature and relative humidity [9]. Hot chambers within these caves, where temperatures can reach up to 40 °C and relative humidity is ≥ 90%, are crucial for the development of young bats and the maintenance of a relatively high and constant body temperature [9, 16, 30]. Such specific habitat requirements reinforce the importance of those bat caves, which may be considered exceptional ecological sites [27, 44] and unique environments due to a combination of biotic and abiotic interactions [6, 7, 45]. Although caves with exceptional bat populations are present in countries across South, Central, and North America (e.g [6, 7], those holding Pteronotus populations are not abundant. In Brazil’s Caatinga drylands, only ten bat caves are known (E. Bernard, personal communication), and the nine caves surveyed here are the only ones with Pteronotus bats. Thus, our results not only encompass all Pteronotus colonies regionally known to date but also reinforce the strict roost dependency of these species, and highlighting the urgent need to protect these habitats and their ecological functions.

In Brazil, the ranges of P. personatus and P. gymnonotus broadly overlap [15], and in the Caatinga drylands, they frequently share roosts (e.g [9, 18]). However, P. personatus was found in only four of the nine surveyed caves, highlighting its more restricted distribution compared to P. gymnonotus, which occurred in all caves. This restricted distribution of P. personatus is consistent with bioacoustic and ecological data (e.g [9, 20, 46]) and may reflect narrower habitat preferences or ecological constraints not faced by P. gymnonotus. Ecological theory predicts that species with wider distributions and higher local abundance function as generalists, exhibiting higher gene flow and lower genetic structuring [47]. In contrast, specialist species are typically rarer and more prone to population differentiation [47, 48]. Within this framework, our results suggest that P. gymnonotus behaves as a generalist, with high abundance and genetic connectivity across caves, while P. personatus shows traits of a more specialized species. Nonetheless, contrary to expectations for specialists, P. personatus in the Caatinga only exhibited weak signs of genetic structuration. This suggests that other ecological or behavioral traits may help maintain connectivity across its more limited distribution, and stronger structuring can be observed across its broader range or under scenarios of habitat fragmentation.

Additionally, our results suggest differences in habitat use and ecological tolerance, highlighting the importance of species-specific ecological dynamics in shaping population genetic structure. The restricted distribution of P. personatus, recorded in only four of the nine surveyed caves, indicates potential ecological limitations. These may be associated with habitat specificity, interspecific competition, or other ecological constraints that limit its occurrence to fewer roosting sites. P. personatus appears to rely heavily on the hot chambers of bat caves for reproduction [16], which may reduce its dispersal capacity and increase its susceptibility to habitat fragmentation. Such ecological specialization can influence movement patterns and promote genetic isolation among subpopulations, a pattern also observed in other taxa such as plants (e.g [49]), invertebrates (e.g [50]), birds (e.g [51]), lizards (e.g [52]), and bats (e.g [53]). Although some studies indicate that gene flow may still occur at fine spatial scales among ecologically similar sites (e.g [51, 54]), three lines of evidence suggest that P. personatus may still exhibit strong population genetic structure across its full distribution range: (1) its lower local abundance, with presence confirmed in only a subset of caves; (2) its apparent dependence on specific environmental conditions; and (3) the patterns of genetic diversity observed in this study. These factors, considered together, highlight the importance of broader-scale studies to fully understand the population dynamics and conservation needs of this species.

In contrast, the widespread presence of P. gymnonotus across all surveyed caves suggests that this species has a broad ecological tolerance. In fact, this species is distributed across a wide range of habitats in the Neotropics, from southeastern Mexico through Central and South America, including northeastern Brazil [18]. However, it is important to note that this abundance pattern applies to the species’ southern range. In the northernmost distribution, populations are much smaller, with colonies of fewer than 30 individuals [55]. Additionally, as an aerial insectivore, P. gymnonotus forages in open areas and gallery forests, further demonstrating its ability to exploit diverse habitats [18]. This ecological flexibility suggests a high level of adaptability and likely contributes to its high genetic connectivity and resilience to environmental changes. Together with the restricted distribution of P. personatus in the Caatinga, these contrasting patterns highlight the complexity of ecological dynamics within the genus and reinforce the need for a landscape-scale approach to conservation.

Furthermore, the absence of hybridization between P. gymnonotus and P. personatus, despite their frequent co-roosting, underscores their distinct evolutionary identities and potential ecological partitioning. Hybridization events in bats have been documented in other contexts, such as between P. gymnonotus and P. fulvus in Mexico, where introgression occurred between two closely related and sympatric species [56], and in Myotis bats, particularly at swarming sites where large mixed colonies form [57, 58]. These cases demonstrate that while hybridization is possible within the genus or among closely related bat taxa, it does not occur between P. gymnonotus and P. personatus, further emphasizing the complexity of their coexistence and distinct ecological trajectories.

Globally, multiple studies have already reported the impacts of small isolated populations and low levels of genetic diversity on species´ persistence [22, 59, 60]. However, other studies have shown that genetic diversity alone is not enough to fully assess the conservation status of a species [60] and the maintenance of gene flow among populations is essential to safeguard the species´ long-term survival [22, 61]. Therefore, identifying and understanding the drivers of gene flow is imperative for species conservation. Here, the analysis of the population genetic structure of two Pteronotus species suggests that although geographic distance may influence gene flow, the patterns we observed do not constitute a clear case of Isolation by Distance. Pairwise FST values and Mantel test results indicate ongoing connectivity among caves, especially for P. gymnonotus and, to a slightly lesser extent, for P. personatus. Since geography is only one of the key components that can influence population connectivity [62, 63], other factors – or a combination of them – could be driving the population genetic structure in the species (e.g [53, 64]), which appears to be the case for the two Pteronotus species we studied.

Furthermore, population genomic studies of bats using high-resolution markers such as SNPs or UCEs are extremely rare, making comparative analyses crucial for understanding dispersal ecology and the drivers of population structure. Alongside our genomic analyses of Pteronotus gymnonotus, a key example is the study by Lilley et al. [32] on the Chilean Myotis, Myotis chiloensis, which also employed ddRAD-seq to analyze genome-wide SNPs. In M. chiloensis, populations exhibited strong genetic structure and pronounced isolation-by-distance, with higher genetic diversity observed in southern populations (HO up to 0.3248). In contrast, Pteronotus bats in the Caatinga displayed low genetic differentiation (FST generally < 0.05), and no significant correlation between genetic and geographic distance. Heterozygosity values further highlight these contrasts: HO ranged from 0.236 to 0.239 and HE 0.256–0.266 for P. personatus, and HO 0.204–0.274 and HE 0.226–0.267 for P. gymnonotus, whereas M. chiloensis populations reached HO 0.255–0.3248 and HE 0.279–0.3335. Similarly, inbreeding coefficients were consistently higher in P. personatus (FIS = 0.059–0.081) compared with the low or slightly negative values observed in P. gymnonotus, while M. chiloensis populations exhibited FIS ranging from 0.021 to 0.058. Notably, the geographic patterns of diversity differ between these genera: in M. chiloensis, genetic diversity increases from north to south, with strong population differentiation (FST up to 0.113) and clear isolation-by-distance, whereas both Pteronotus species show relatively homogeneous diversity across caves, low FST values, and no significant correlation between genetic and geographic distance. These contrasts suggest that Pteronotus populations in the Caatinga form largely panmictic units, maintaining high connectivity via dynamic roost use and presumed long-distance mating movements across the cave network, in stark contrast to the highly structured, spatially isolated populations of M. chiloensis.

For many species, gene flow is not a direct result of migration to a new population. Instead, it can occur through mating events, when individuals temporarily disperse to mate and then return to their original populations [65,66,67,68]. In these cases, bats congregate to mate at swarming sites, promoting genetic mixing among populations (e.g [69,70,71]). These temporary movements can be driven by either female and/or male dispersal and may or may not have a clear seasonal pattern [66, 70, 72]. In fact, we [27] have already suggested that movements related to reproduction are the main factor shaping population genetic structure in P. gymnonotus. The lack of population structure and the high level of genetic diversity for P. personatus also suggest that reproductive strategies play an important role. This would explain the level of genetic connectivity between populations of geographically distant caves. Previous studies have reported nursery colonies and movement of adult male individuals among bat caves for P. gymnonotus [17, 19, 20, 73], which may explain the level of connectivity among all nine subpopulations studied.

Taken together, these results reinforce that, for P. personatus, the weak signals of population structuring we observed are not indicative of fully differentiated clusters but rather suggest high connectivity among the caves studied. However, given that we only sampled a portion of the species’ distribution and the ecological drivers of dispersal and roost selection remain largely unknown, broader landscape-scale studies are needed to understand potential future structuring. In this context, conserving the network of bat caves is critical to maintaining genetic diversity and connectivity, ensuring long-term population persistence for both Pteronotus species.

Conservation implications

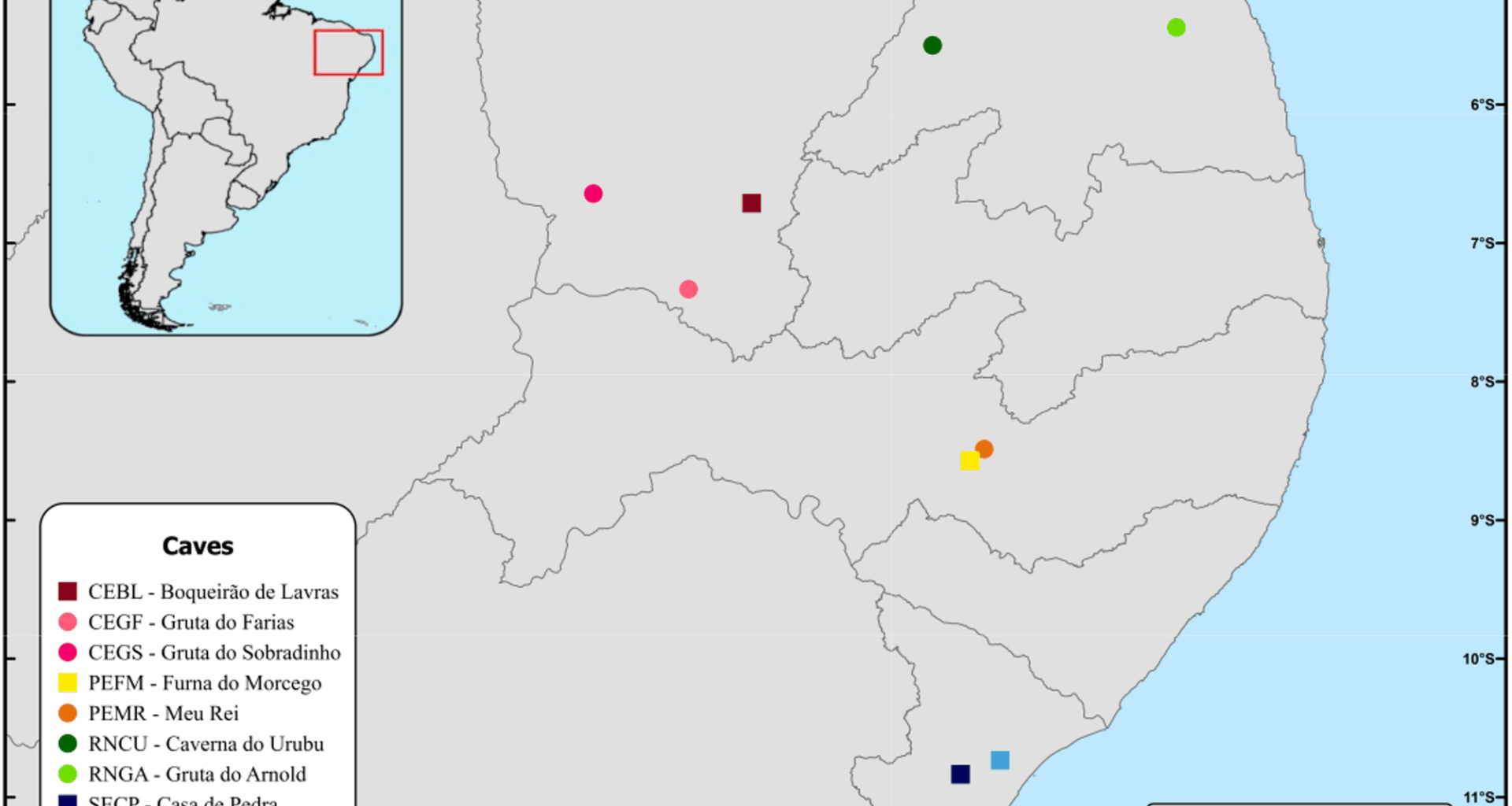

Our results emphasizes that Pteronotus species in northeastern Brazil have a very dynamic roost use, based on a network of caves, pointing out that conservation initiatives for the genus must not be based solely on a single site protection approach but, rather, on a landscape perspective. Cave management and conservation plans should consider the genetic information produced, and bat caves in Brazil must be managed as a network of roosts harboring very mobile individuals and hotspots for gene flow (e.g [7]). Pteronotus personatus was found in only four caves (Boqueirão de Lavras, Furna do Morcego, Urubu and Casa de Pedra), pointing out that such caves are extremely important as reproductive sites. The caves sheltering only P. gymnonotus are similarly important for bat conservation and must be protected, since they form a network of shelters, and should be studied closely to identify the reasons for P. personatus absence.

Our data highlight the need for further in-depth ecological studies on cave-dwelling bats in Brazil. In the case of P. personatus, for example, a taxonomic review is imperative considering that studies including molecular and morphological data have pointed out the possibility of a species complex [14, 74, 75], but with a pending description of the possible species. Similarly, updated data on the species distribution range and reproductive patterns are important and would help on the interpretation of the current population genetics results.

Finally, the evidence of long-distance mating movements presented here, especially for P. gymnonotus, together with the signs of structuration for P. personatus, highlights the importance of adopting a landscape genetics perspective for bat and cave conservation in the Caatinga. Even low levels of genetic differentiation underscore the need to preserve the entire network of roosts to maintain connectivity and safeguard genetic diversity. Current evidence has shown that the Caatinga is, in fact, a very dynamic and heterogeneous system, shaped by multiple ecological processes at different spatial and temporal scales along its area [76], and anthropogenic disturbance is unevenly distributed across the landscape [77], negatively impacting the bat activity in the region [78]. Thus, the landscape around the bat caves studied is under different degrees of anthropic pressure and, due to the complex use the different bat species make of them, both could be negatively impacted by habitat loss and degradation.

Considering the results presented here, both species of Pteronotus have a strict relationship with the bat caves. Thus, maintaining the genetic connectivity among the caves is essential for both species’ survival and the cave ecosystem. Pteronotus bats have been identified as an umbrella-taxa for both bats and caves in Brazil (e.g [9]). Their presence can influence bat diversity, including threatened species [9, 79]. The guano they produce is essential for the maintenance of several endemic cave species [80] and some subterranean ecosystems. In fact, their role as bioengineers has been recently addressed in Amazonian iron ore caves [45]. Moreover, bats in bat caves provide many other ecosystem services, such as the control of arthropod populations [20]. Therefore, setting the network of bat caves as priority for conservation would benefit both bats, the ecosystem services they provide, and the general speleological heritage in Brazil.