September 11, 2025

When shocking news about how soon civilization might collapse is overshadowed by Taylor Swift’s engagement, we might have a problem.

A man on a rooftop looks at approaching flames as the Springs fire continues to grow on May 3, 2013 near Camarillo, California.

(David McNew / Getty Images)

This story is part of The 89 Percent Project of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration cofounded by Columbia Journalism Review and The Nation strengthening coverage of the climate story.

This story is part of The 89 Percent Project of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration cofounded by Columbia Journalism Review and The Nation strengthening coverage of the climate story.

Chances are you’ve heard that Taylor Swift is getting married. When she and Travis Kelce announced their engagement last month, it was all over the news, all over the world.

Chances are equally good that you did not hear some other, literally Earth-shaping news that broke two days later. On August 28, some of the world’s foremost climate scientists dramatically revised their estimate of how soon one of the foundations of Earth’s climate system could collapse.

Media’s obsession with one story—and its ignoring of the other—highlights the gaps that remain in treating the climate crisis like the cataclysm it has become. While progress has been made in many newsrooms, old journalism habits linger, including sidelining important climate news out of misguided fears that it’s depressing or too complicated. As CCNow’s 89 Percent Project has shown, that’s not how most readers or viewers see it.

The collapse of what is commonly called the Gulf Stream—the vast Atlantic ocean current that scientists refer to as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, AMOC—would deal a crushing blow to civilization as we know it. Sometimes known as Europe’s “central heating unit,” the AMOC is why Britain, France, The Netherlands, and their northern neighbors enjoy relatively mild winters, even though they sit as far north as Canada and Russia.

AMOC originates in the Caribbean, where sun-warmed sea water flows northeast across the Atlantic toward Greenland. The amount of heat AMOC transports is staggering: 50 times more heat than the entire world uses in a year. Without AMOC, the history and present day of Europe would look very different. Winters would be much colder and longer. Food production would be much less, as would the human population and infrastructure the region could support.

The scientific study released on August 28 concluded that AMOC’s collapse “can no longer be considered a low-likelihood event,” to quote The Guardian, one of the very few outlets to report the news. Indeed, such a collapse is more likely than not if humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions remain on their current trajectory. If emissions continue to rise, there is a seven out of 10 chance that AMOC will collapse, the scientists calculated. If emissions fall to a moderate level, the odds are 37 percent—roughly one in three. Even if emissions decline in line with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius, there is a one in four chance of collapse.

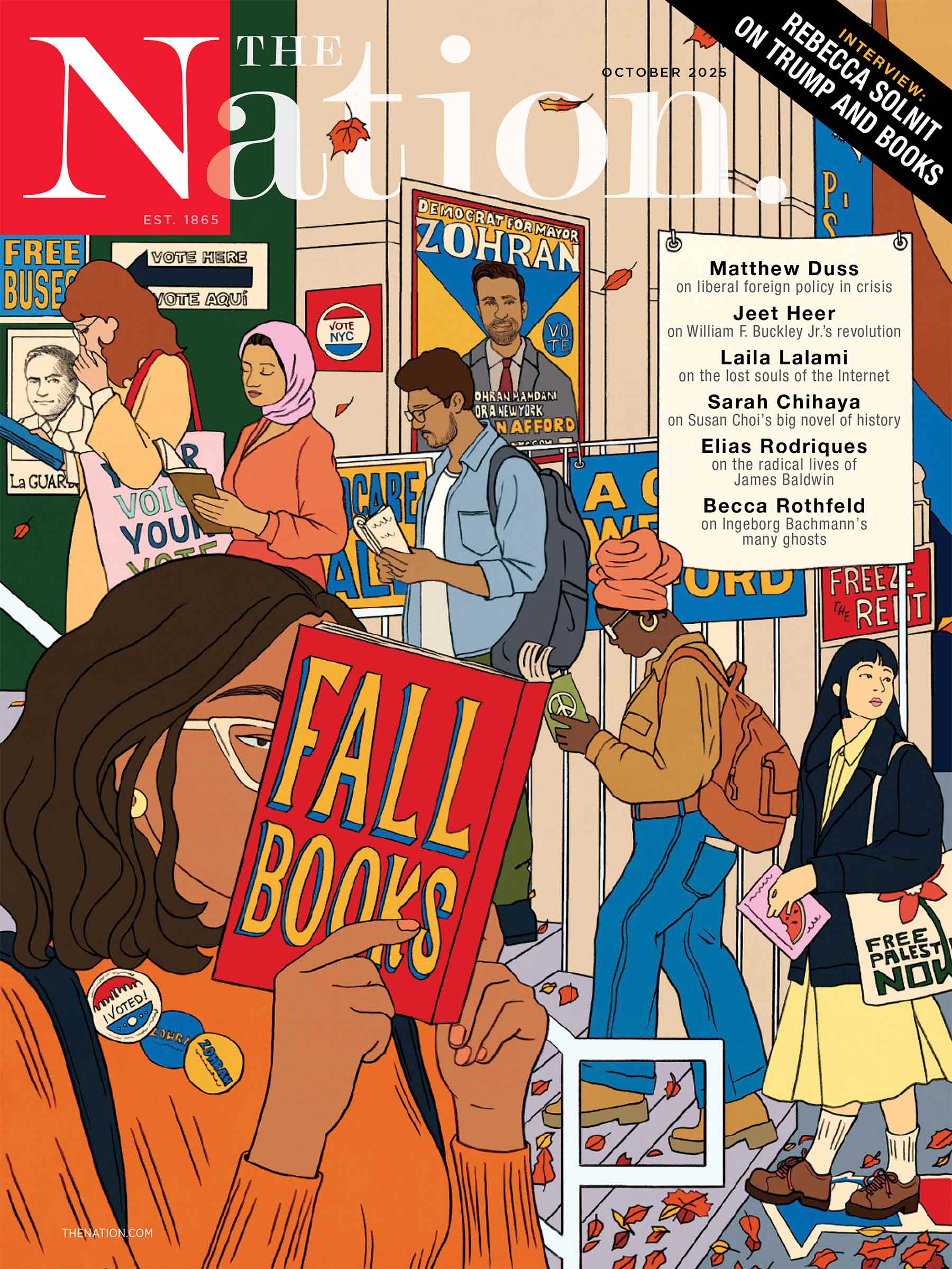

Current Issue

Although the collapse might not occur in this century, the scientists warned that the system could pass a “tipping point” in the next decade or two that makes its eventual collapse inevitable. As 44 scientists explained in an open letter to the Nordic Council of Ministers, AMOC might well collapse in this century, but there is an “even greater likelihood a collapse is triggered this century but only fully plays out in the next.”

The only hope, the scientists added, is a “global effort to reduce emissions as quickly as possible, in order to stay close to the 1.5 [degrees C] target set by the Paris Agreement.”

By no means is northern Europe the only region in peril. A collapse, or even significant slowdown, of AMOC would devastate agriculture in Africa and other parts of the Global South by massively disrupting rainfall patterns.

All of which helps explain why Stefan Rahmstorf of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, who co-authored the new study, was frustrated by how little attention he and his colleagues’ warnings got. “What more can we do to get heard?” he asked. “It’s like the saying that every disaster movie starts with scientists warning and being ignored.”

Donald Trump wants us to accept the current state of affairs without making a scene. He wants us to believe that if we resist, he will harass us, sue us, and cut funding for those we care about; he may sic ICE, the FBI, or the National Guard on us.

We’re sorry to disappoint, but the fact is this: The Nation won’t back down to an authoritarian regime. Not now, not ever.

Day after day, week after week, we will continue to publish truly independent journalism that exposes the Trump administration for what it is and develops ways to gum up its machinery of repression.

We do this through exceptional coverage of war and peace, the labor movement, the climate emergency, reproductive justice, AI, corruption, crypto, and much more.

Our award-winning writers, including Elie Mystal, Mohammed Mhawish, Chris Lehmann, Joan Walsh, John Nichols, Jeet Heer, Kate Wagner, Kaveh Akbar, John Ganz, Zephyr Teachout, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Kali Holloway, Gregg Gonsalves, Amy Littlefield, Michael T. Klare, and Dave Zirin, instigate ideas and fuel progressive movements across the country.

With no corporate interests or billionaire owners behind us, we need your help to fund this journalism. The most powerful way you can contribute is with a recurring donation that lets us know you’re behind us for the long fight ahead.

We need to add 100 new sustaining donors to The Nation this September. If you step up with a monthly contribution of $10 or more, you’ll receive a one-of-a-kind Nation pin to recognize your invaluable support for the free press.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and Publisher, The Nation

Mark Hertsgaard is the environment correspondent of The Nation and the executive director of the global media collaboration Covering Climate Now. His new book is Big Red’s Mercy: The Shooting of Deborah Cotton and A Story of Race in America.